The ruby-throated hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) is a tiny aerial acrobat with iridescent green feathers and, in males, a ruby-red throat patch that flashes like a jewel in sunlight. Ruby-throated hummingbird facts reveal that these remarkable birds visit millions of backyard feeders and gardens each summer, dazzling birdwatchers with their rapid wing beats, hovering ability, and incredible agility.

Their small size and energetic flight make them one of the most captivating backyard birds in North America. These birds rely on high-energy diets, precise feeding habits, and long-distance migration to survive. This guide explores their diet, nesting behavior, migration patterns, and overall ecology, giving readers a complete look at the remarkable life of the ruby-throated hummingbird. 😄

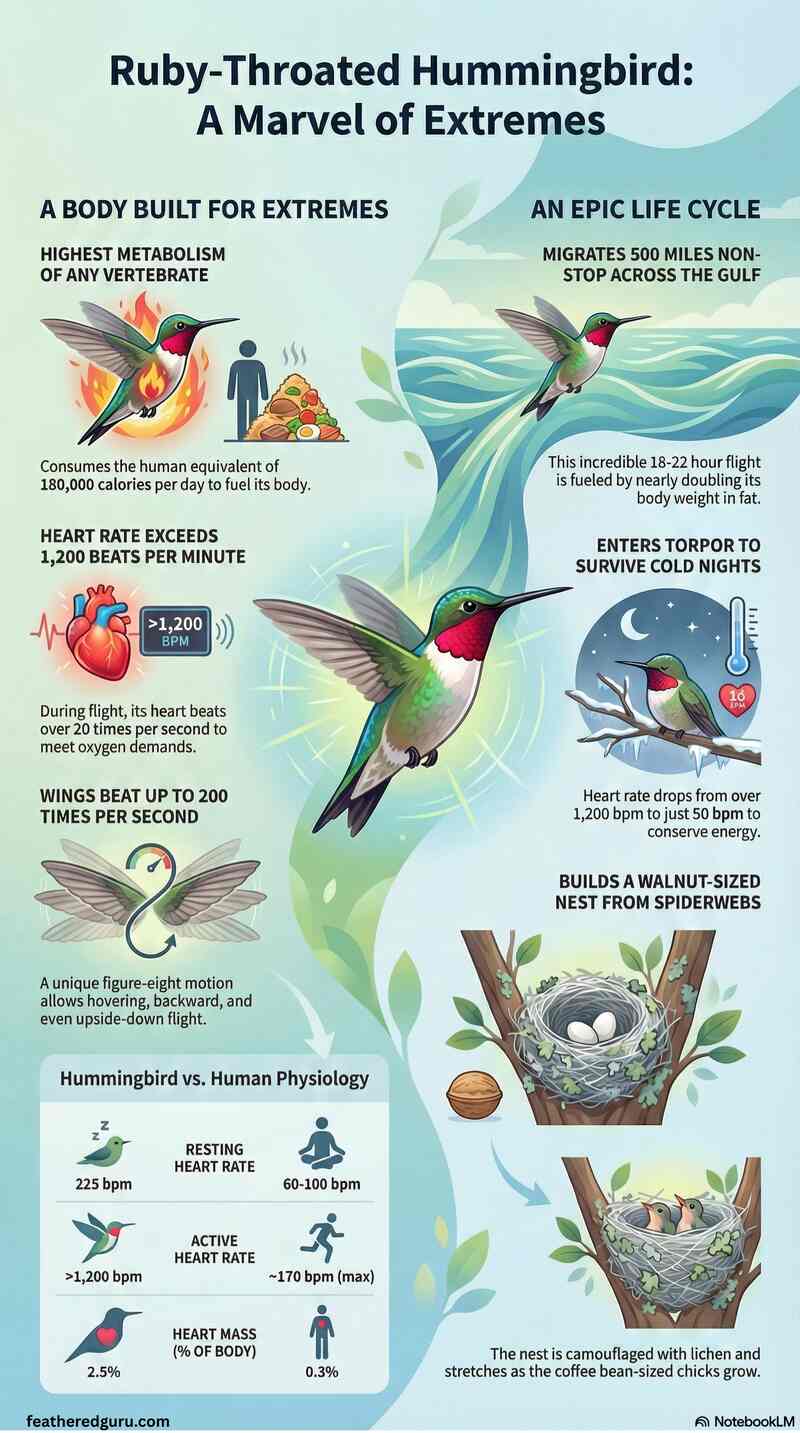

- Tiny aerial acrobats with iridescent green feathers and males’ ruby-red throat patch.

- Measure 7–9 cm long, weigh ~3.4–3.8 grams, wingspan 8–11 cm.

- High-energy diet of nectar and small insects; feed 5–8 times per hour.

- Fastest vertebrate metabolism; heart rates can exceed 1,200 beats per minute in flight.

- Hover, fly backwards, dive, and travel non-stop 500 miles across the Gulf of Mexico.

- Females build tiny, spiderweb-nested nests; 1–3 eggs per clutch; 20–22 day fledging.

- Use torpor to survive cold nights and conserve energy efficiently.

- Exceptional spatial memory allows remembering flower locations, feeders, and territory.

- Face threats from habitat loss, pesticides, climate change, and window collisions.

- Support them with native tubular flowers, sugar feeders, and pesticide-free yards.

For a quick visual recap, check out our infographic at the bottom of this guide.

Ruby-Throated Hummingbird Facts: Explainer Video

Dive deeper into the fascinating biology, flight, diet, and migration of ruby-throated hummingbirds in this detailed explainer video.

Show Transcript:

0:00

Today we are talking about a creature that many of us see all the time, maybe right in our own gardens. The ruby-throated hummingbird. But we are not just here to admire a pretty bird. We are here to get to know a true biological marvel. A tiny machine that absolutely pushes the limits of what should be physically possible.

0:17

Think for a second about the most extreme athlete you can imagine. Someone with unbelievable endurance, blinding speed, and an engine that never quits. What if I told you that athlete is probably flitting around just a few feet from your window right now? That is right. We are talking about the ruby-throated hummingbird.

0:36

This little bird is a powerhouse of evolutionary adaptation, packing more athletic ability into its tiny body than almost any other animal on the planet. An adult hummingbird weighs about 3.4 grams, literally less than a nickel, and is covered in only about 940 feathers.

1:01

The fiery red throat on the male is not pigment. That stunning color is structural. It is created by the way light bounces off microscopic features on the feathers themselves.

1:15

How does a creature this small generate so much power? First, consider its metabolism. It is off the charts. A hummingbird’s heart can beat over 1,200 times per minute in flight. For comparison, a healthy human heart rate is 60 to 100 beats per minute.

1:55

Even when perched, hummingbirds take around 250 breaths per minute to keep oxygen flowing. Adjusted for size, their mass-specific metabolic rate is 77 times faster than a human. They burn energy at a rate that is almost impossible to imagine.

2:20

To fuel its lifestyle, a hummingbird would need the caloric equivalent of a human eating 150,000 calories a day. They live on the edge of starvation from one moment to the next.

2:45

Hummingbirds are extremely efficient feeders. They do not suck nectar like a straw. They lick it. Their forked tongues have tiny fringes that spread in nectar and trap it using capillary action. The nectar is squeezed back into their throat. It is a high-speed, high-tech biological pump.

3:33

With this metabolism, how do they survive the night? They balance incredible energy output with energy conservation. Their flight is legendary. They hover for long periods, fly backwards, and even upside down for a moment. Courtship dives can reach 60 miles per hour, powered by wing beats over 200 times per second.

4:15

At night, they enter torpor, a controlled mini-hibernation. Their heart rate drops from over 1,200 to as low as 50 beats per minute. Their body temperature drops from 105°F to 54°F. Their metabolism slows by up to 95 percent. This allows them to survive until sunrise.

5:02

Their ultimate test is migration. Ruby-throated hummingbirds make a non-stop flight across the Gulf of Mexico, about 500 miles, with no rest. They prepare by eating as if their life depends on it. Fat reserves nearly double their body weight from 3.5 grams to almost 7 grams.

5:55

This is an 18 to 22-hour continuous flight. A single sustained effort by a creature small enough to sit on your thumb. It is an act of endurance that defies belief.

6:10

When you consider metabolism, feeding, flight, and survival strategies together, it becomes clear. This is not just a bird. It is a tiny architect of its environment. It has the fastest metabolism on the planet. It can enter a state of suspended animation to survive the night. It completes epic solo migrations guided by instinct. Its aerial acrobatics are unmatched.

6:40

While doing all of this, the ruby-throated hummingbird serves as a critical pollinator for countless native plants, holding ecosystems together. The ruby-throated hummingbird proves that the most extraordinary things often come in the smallest packages.

6:57

It leaves us with a question. What other incredible biological marvels are hiding in plain sight around us, waiting for us to look closer and truly see them?

Physical Characteristics: Tiny But Mighty

Size and Weight: According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, ruby-throated hummingbirds measure just 7-9 cm (2.8-3.5 inches) long with an 8-11 cm (3.1-4.3 inches) wingspan. Males average 3.4 grams while females are slightly larger at 3.8 grams. Both weigh approximately one-tenth of an ounce, which is less than a U.S. nickel.

Plumage and Sexual Dimorphism: The ruby-throated hummingbird is sexually dimorphic. Adult males have metallic green backs and crowns with a striking ruby-red gorget (throat patch) edged in velvety black.

According to the Audubon Field Guide, the male’s gorget, or iridescent ruby throat, “looking black in most lights,” shows red iridescence that is highly directional and appears dull black from many angles. The color comes from feather structure rather than pigment, creating a shimmering effect that changes with light.

Females have green, black, and white notched tails and white throats that may show faint dusky markings. Their subtler plumage helps with camouflage while nesting and feeding.

Feathers: Ruby-throated hummingbirds have around 940 feathers, making them one of the bird species with the fewest feathers overall, according to Journey North’s hummingbird research. Despite the low feather count, every single feather is replaced each year during a full molt that happens mainly on their wintering grounds.

Bill and Feet: The bill extends up to 2 cm (0.79 inches) and is long, straight, and slender, perfectly adapted for accessing tubular flowers. According to research, their legs are extremely short, with feet that have three toes pointing forward and one backward. These toes form small claws with ridged inner surfaces that help them grip flower stems.

However, these tiny feet prevent walking or hopping. Ruby-throated hummingbirds can only perch or shuffle sideways along branches, as explained in how hummingbird legs are designed for perching, not walking.

Metabolism: The Fastest in the Animal Kingdom

Ruby-throated hummingbirds possess the highest mass-specific metabolic rate of any vertebrate on Earth. According to research published in Experientia by Suarez (1992), “Small hummingbirds achieve the highest known mass-specific metabolic rates among vertebrate homeotherms.”

Heart Rate: A ruby-throat’s heart beats 225 times per minute at rest, accelerating to over 1,200 beats per minute during flight according to the Smithsonian National Zoo. Compare this to human resting heart rates of 60-100 beats per minute. Research from Johns Hopkins Medicine notes their hearts comprise up to 2.5% of body weight, while in humans, hearts account for only 0.3% of total body mass.

Breathing Rate: Even at rest, ruby-throats breathe approximately 250 times per minute. During flight, breathing accelerates further to meet extreme oxygen demands.

Oxygen Consumption: Hummingbird metabolism operates at extraordinary rates. According to research published in PMC on adipose energy stores, “At rest, oxygen consumption is about 4 ml O2/g/h. During flight, hummingbird oxygen consumption per gram of muscle tissue is approximately 10 times higher than that seen for elite human athletes.”

Feeding Requirements: According to Johns Hopkins Medicine research, ruby-throats need extraordinary caloric intake, roughly “the human equivalent of 150,000 calories per day”, to maintain their metabolism 77 times faster than a human’s. They consume approximately half their body weight in nectar and insects daily, feeding 5-8 times per hour throughout daylight hours.

Digestion Speed: Hummingbirds process food extraordinarily quickly due to their high metabolic rate, with rapid gut transit times enabling frequent feeding throughout the day.

Blood Sugar Levels: Ruby-throats maintain blood glucose levels significantly higher than most vertebrates. According to PMC research on hummingbird adipose energy, despite seasonal body fat exceeding 40% of body weight and elevated blood sugar, hummingbirds don’t develop diabetes. They possess unique metabolic adaptations including efficient glucose recovery from urine.

Flight Capabilities: Masters of the Air

Ruby-throated hummingbirds demonstrate flight capabilities unmatched by almost any other bird.

Wing Beat Frequency: According to the Smithsonian, ruby-throat wings beat approximately 53 times per second during normal forward flight and up to 80 times per second while hovering. During courtship dives, wing beats can exceed 200 times per second.

Unique Wing Structure: According to Britannica, hummingbirds have long, blade-like wings connecting to the body only at the shoulder joint. This allows wings to rotate almost 180 degrees. Wings move in a horizontal figure-eight pattern, generating lift on both forward and backward strokes in a 75%:25% ratio respectively, similar to insect flight mechanics.

Muscle Adaptations: Pectoral (chest) muscles comprise 25-30% of body weight, the highest percentage of any bird group. These massive flight muscles, combined with a relatively short, strong humerus bone, enable extreme maneuverability and sustained hovering.

Flight Capabilities:

- Forward flight: 20-30 mph average speed

- Diving speed: Up to 60 mph during courtship displays

- Hovering: Sustained hovering for extended periods while feeding

- Backwards flight: Can fly backwards with precision

- Upside-down flight: Brief inverted flight capability

- Vertical take-off and landing: Like a helicopter

Daily Distance: According to migration research, ruby-throats can travel substantial distances during migration. During Gulf crossings, they may fly up to 500 miles non-stop, an 18-22 hour continuous flight.

Torpor: Controlled Hypothermia for Survival

One of the ruby-throated hummingbird’s most remarkable adaptations is its ability to enter torpor, a controlled state of hypothermia that dramatically reduces energy expenditure.

What is Torpor? According to the Smithsonian National Zoo, torpor is “a very deep, sleep-like state” where metabolic functions slow to a minimum and body temperature drops significantly. Ruby-throats maintain normal body temperatures around 105°F (40.5°C) during active periods but can lower this substantially overnight.

Physiological Changes: During torpor, according to research from Birds & Blooms:

- Heart rate drops from 500-1,200 beats per minute down to as low as 50 beats per minute

- Metabolism slows by up to 95%

- Body temperature can drop to around 54°F (12°C)

Why Torpor is Necessary: According to the Smithsonian National Zoo, hummingbird feathers provide poor insulation. Combined with their incredibly high metabolic demands and tiny body size (which loses heat rapidly), ruby-throats cannot maintain 105°F body temperature throughout cold nights without depleting all fat reserves. Torpor allows them to conserve precious energy when they cannot feed.

Recovery Process: Each morning, ruby-throats speed up their metabolism within minutes, returning body temperature and heart rate to normal active levels. This rapid recovery distinguishes torpor from true hibernation, which involves prolonged periods of reduced metabolic state.

Frequency of Use: According to the Smithsonian, hummingbirds can enter torpor any night of the year when temperature and food conditions demand it, making them masters of this survival strategy.

Migration: Epic Journeys for Tiny Birds

Ruby-throated hummingbird migration represents one of nature’s most impressive feats relative to body size.

Range and Distance: Ruby-throats breed throughout eastern North America from southern Canada to the Gulf Coast. According to Audubon, they winter from Mexico south to Costa Rica and Panama, with some remaining along the Gulf Coast and southern Florida. Round-trip migration can exceed 2,000 miles for northern populations.

Gulf of Mexico Crossing: Perhaps the most famous aspect of ruby-throat migration is the potential trans-Gulf flight. According to the U.S. Forest Service, portions of the population fly non-stop approximately 500 miles (800 km) across the Gulf of Mexico, an 18-22 hour continuous flight over water where food and rest are impossible.

Pre-Migration Fattening: Research published in Premigratory fattening, torpor, and energy management in ruby-throated hummingbirds shows that ruby-throated hummingbirds significantly increase body mass before migration, with gains driven primarily by rapid fat accumulation rather than lean tissue.

According to Wikipedia’s ruby‑throated hummingbird summary, this stored fat enables them to fuel their nonstop Gulf of Mexico crossing, which can last around 20 hours.

Recent Migration Research Findings: Contrary to long-held beliefs, fall migration routes and timing in Ruby‑throated Hummingbirds don’t mirror spring patterns.

According to hummingbird expert Sheri Williamson, based on citizen science and migration observations, these fall routes often involve different stopover strategies rather than a simple trans‑Gulf crossing.

Recent research confirms this distinction, showing clear differences in timing, routes, and stopover behaviors between spring and fall migrations:

Spring Migration (March-May):

- eBird data shows ruby-throats concentrate heavily on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula in March-April

- Many fly trans-Gulf from Yucatán to U.S. Gulf Coast (Louisiana, Alabama, Florida)

- Males arrive slightly earlier than females

Fall Migration (August-October):

- Research published in Movement Ecology using hydrogen stable isotope analysis found ruby-throats exhibit Type 1 chain migration, with southern breeding populations migrate before northern populations

- Juvenile ruby-throats use overland routes around the Gulf rather than crossing it, according to Alabama coastal studies

- Adults likely also take overland routes in fall, though farther inland than juveniles

- eBird data shows Yucatán Peninsula has very few ruby-throats August-November, confirming circum-Gulf routes dominate in fall

- Study of offshore oil platforms found fall detections had distinct western bias, with Texas coast accounting for 58% of sightings

Solo Migration: Ruby-throats migrate individually, not in flocks. According to migration tracking research, young birds navigate their first migration without parental guidance, relying on innate directional programming and environmental cues.

Feeding Behavior: Nectar, Insects, and Adaptation

Primary Diet: Ruby-throats are specialized nectar feeders but also consume significant quantities of small arthropods. According to research, while hummingbirds are well‑known as nectar feeders, they also consume small insects and spiders to obtain essential protein, fats, and micronutrients that nectar alone doesn’t provide.

Tongue Mechanics: Contrary to common belief, ruby-throats don’t suck nectar. According to research documented across multiple sources, they lick nectar with fringed, forked tongues. Capillary action along the tongue fringe helps draw nectar into the throat for swallowing. Their tongues flick in and out 10–15 times per second while feeding, as shown in peer-reviewed research on hummingbird tongue mechanics.

Flower Preferences: Research shows slight preference for red, orange, and bright pink tubular flowers, though ruby-throats visit flowers of all colors. Preferred native species include trumpet creeper, cardinal flower, jewelweed, coral honeysuckle, and bee balm. About 19 plant species in the eastern U.S. have co-evolved with hummingbirds.

Insect Consumption: Young birds are fed insects exclusively during nestling period since nectar provides insufficient protein for growth. Adults catch insects on the wing, glean them from foliage and bark, or take them (including trapped prey) from spider webs.

Sap Feeding: According to Audubon, ruby-throats arriving in early spring before most plants bloom tap an unexpected resource: sap from Yellow-bellied Sapsucker drill holes. They will even build nests near these sap wells to access this reliable early-season food, feeding on both sap and the insects attracted to it.

Feeder Use: Ruby-throats readily visit sugar-water feeders, often defending them aggressively against other hummingbirds. However, research from Texas documented that when both natural flowers and feeders are available, ruby-throats prefer natural nectar sources.

Breeding Biology: Solitary Nesters

Territoriality: Adult ruby-throated hummingbirds of both sexes are highly territorial and aggressive toward other hummingbirds. Males defend feeding territories during breeding season, attacking and chasing intruders.

According to research, males perform elaborate aerial courtship displays, swooping from heights up to 50 feet into a series of looping U‑shaped dives to impress females, producing twittering wing sounds and high‑pitched vocalizations, as documented by the American Bird Conservancy.

Mating System: Ruby-throats are polygynous. Males mate with multiple females, providing no parental care. Once mating occurs, the male’s involvement ends entirely. The female handles all nest construction, incubation, and chick-rearing alone.

Nest Construction: According to Audubon, females build tiny walnut-sized nests using plant matter woven together with spiderwebs collected by sticking them to beak and breast. Lichen camouflages the exterior while down from thistle and dandelion cushions the interior. The spiderweb construction allows nests to stretch as chicks grow. Nests are typically placed on small downward-sloping branches 10-40 feet above ground, often over water or at forest edges.

Eggs and Incubation: Females lay 2 eggs (occasionally 1 or 3) about the size of Roosevelt’s head on a U.S. dime, approximately coffee bean-sized. According to Cornell research, incubation lasts 11-16 days with the female alone incubating and brooding.

Nestling Period: Young fledge at 20-22 days old. During this period, the female feeds them insects and regurgitated nectar constantly. According to Cornell, females sometimes begin building a second nest while still feeding young in the first, allowing for 1-2 broods per year, occasionally 3 in southern populations.

Lifespan and Survival

Average Lifespan: Most ruby-throated hummingbirds live 3–5 years in the wild, with the oldest known female reaching 9 years, 2 months, according to All About Birds.

Sex Differences in Longevity: Research and long-term banding data show that in Ruby‑throated Hummingbirds, females tend to have higher survival rates than males, with many of the longest-lived individuals recorded as female and males often not surviving past five years. Higher male mortality is thought to result from the intense energy demands of territory defense during breeding and the costs of migration, according to long-term banding research.

Predators: According to Cornell research, despite their small size and vulnerability, free-flying adult ruby-throats are too nimble for most predators. Chief predators include swift raptors like sharp-shinned hawks, merlins, American kestrels, and Mississippi kites, plus domestic cats, loggerhead shrikes, and greater roadrunners, all likely to ambush sitting or sleeping birds.

Conservation Status: Ruby‑throated hummingbirds remain abundant throughout their range, with an estimated population of around 35 million individuals according to the IUCN Red List.

According to Forest Service research, they’re protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and listed in CITES Appendix II. However, maintaining and protecting habitats and nectar plants along migration routes remains critical for continued population health.

Vocalizations and Communication

Sound Production: Ruby-throats are not songbirds and produce limited vocalizations. According to Cornell research, their calls consist of rapid, squeaky chirps primarily used for threats. Males vocalize to warn other males entering their territory.

Wing Sounds: During courtship displays, males produce rapid tik-tik-tik sounds with their wings, created both during shuttle displays and dive displays. A fainter whining sound is sometimes produced with outer tail feathers during dives as males spread and close their tails while flying over females.

Intelligence and Memory

Hummingbird intelligence often surprises researchers. According to PMC research on hummingbird hippocampus, the hippocampal formation (brain region responsible for spatial memory) in hummingbirds is “two to five times larger than that of caching and non-caching songbirds, seabirds and woodpeckers” when expressed as percentage of telencephalic volume, “significantly larger, relative to telencephalic volume, than any bird examined to date.”

Spatial Memory: Ruby-throats remember individual flowers, feeders, and territories. According to research on rufous hummingbirds published in Learning & Behavior, hummingbirds demonstrated the ability to avoid previously emptied flowers “for retention intervals ranging from a few minutes to over an hour.”

According to University of Lethbridge researcher Andy Hurly, wild hummingbirds remember where they once found nectar and can return within about 70 cm of an emptied source, even if the flower is no longer there, reflecting strong spatial memory in foraging.

Research published in Current Biology showed that hummingbirds can distinguish between flowers refilled at 10‑ versus 20‑minute intervals, remember where flowers are located, and recall when they last drained them, demonstrating sophisticated episodic‑like memory in their foraging.

Route Fidelity: Individuals often return to the same breeding territories and feeders year after year, demonstrating remarkable spatial memory and navigation abilities despite their tiny brain size. This site fidelity reflects both innate navigation capabilities and learned spatial information retained across migrations.

Supporting Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds

Native Plant Recommendations: For comprehensive guidance on attracting hummingbirds naturally through native plantings, prioritize tubular flowers blooming spring through fall, including coral honeysuckle, trumpet vine, cardinal flower, bee balm, and wild columbine.

Supplemental Feeding: Sugar-water feeders (1 part white sugar to 4 parts water, no dye) provide valuable supplemental nutrition. For detailed guidance on when hummingbirds migrate south, understanding timing helps you know when to maintain feeders.

Avoiding Pesticides: Insects comprise essential protein for ruby-throats, especially during breeding season. Pesticide use eliminates this critical food source.

Ruby-Throated Hummingbird: Key Facts at a Glance

Before we wrap up, check out this infographic highlighting key facts about Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds at a glance.

Conclusion: Appreciating a Biological Marvel

Ruby-throated hummingbirds push vertebrate physiology to its limits, with heart rates exceeding 1,200 beats per minute, the ability to hover and fly backwards, and non-stop migrations of up to 500 miles. They can enter torpor, nearly double their body weight in days, and maintain blood sugar levels that would be lethal for humans, showcasing extraordinary evolutionary adaptations.

Despite these feats, they face threats from habitat loss, pesticides, climate-driven changes in flower timing, and window collisions. Understanding their biology deepens our appreciation and highlights the importance of conservation, so future generations can continue to marvel at these aerial jewels visiting eastern North American gardens.