Spring migration sends millions of birds north, creating a short window when flowering plants decide whether yards become refueling stops or flyover zones. Choosing the best plants to attract birds in spring supports birds on multiple levels, from nectar for hummingbirds to native foliage that sustains insects eaten by warblers and tanagers.

This guide is for gardeners who want to attract migrating and nesting birds through intentional plant choices, not decorative ornamentals. Research shows that regional nativeness strongly affects whether birds linger or establish breeding territories. Drawing on ornithological research, field studies, and regional planting data, this guide identifies the most effective native flowering plants for attracting spring birds across North America. 🙂

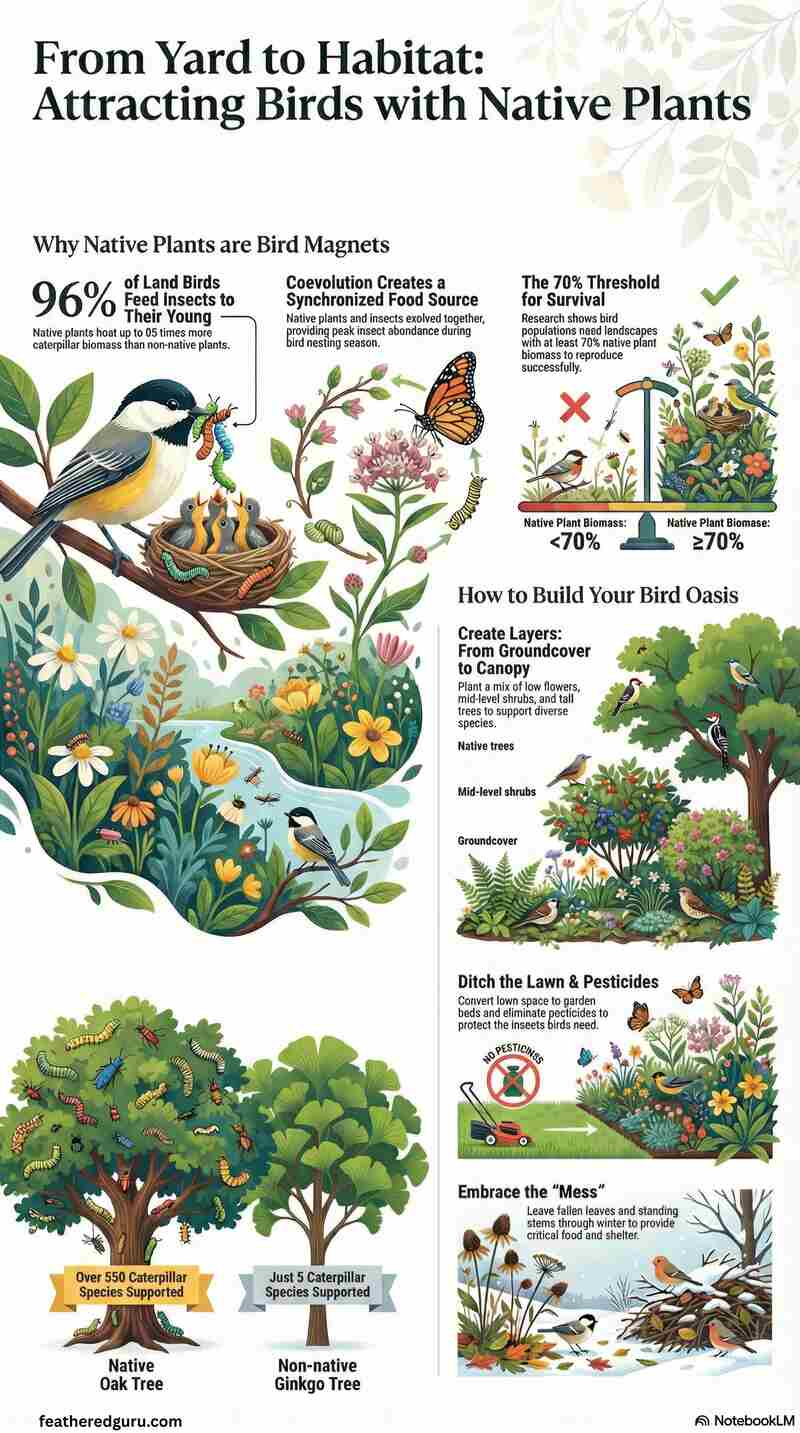

- Spring migration creates a short, critical feeding window for birds.

- Native plants support up to 35× more caterpillars than non-natives.

- About 96% of terrestrial birds rely on insects to feed their young.

- Oaks, cherries, serviceberry, and native flowers drive insect abundance.

- Hummingbirds use early-blooming natives as first nectar sources.

- Yards need ~70% native plant biomass for nesting success.

- Layered vegetation (groundcover, shrubs, trees) attracts more species.

- Eliminating pesticides is essential for a functional bird food web.

- Native gardens outperform feeders alone for spring bird diversity.

Best Plants to Attract Birds in Spring

Watch this quick explainer to see which native plants will bring the most birds to your yard this spring.

Show Transcript:

0:00

You know that feeling when spring finally hits? You start to hear the birds chirping again and see them at the feeder. It’s a classic sign of the season.

0:08

But what if I told you there is a whole hidden drama playing out right in our own backyards? The choices we make, the plants we pick, have a massive impact.

0:22

So here’s the big question. Is your garden actually helping birds or could it be hurting them? It sounds simple, but the answer is much more complicated.

0:35

We all love a beautiful lawn and perfect flower beds. We think it’s paradise for wildlife. But the science tells a different story. Today we’ll dig into how gardens can be a lifeline or a dangerous illusion.

0:52

Let’s start with a wild idea. What if your perfectly manicured garden is actually a trap? For local birds, a yard that looks lush and inviting can have nothing to eat.

1:08

There is a scientific term for this. It’s called an ecological trap. Many conventional gardens send the right signals, like green leaves and pretty flowers, but when birds search for food for their babies, they find nothing.

1:29

That is the heart of the problem. Most plants at garden centers, popular ornamentals, are basically inedible for the local insects that birds rely on. It’s like a pantry stocked with plastic food. No insects means no bird food.

2:01

So what is the fix? It all comes down to insects, and not just any insects. Caterpillars are essential. Ninety-six percent of North American land birds rely completely on insects to feed their young.

2:25

Bird seed and berries are great for adults, but chicks need soft, protein-packed bugs, especially caterpillars. Not all plants provide this food. A native oak tree supports over 550 caterpillar species.

2:46

A non-native ginkgo tree, by contrast, supports only five species. That’s a huge difference in available food. A single pair of chickadees can need up to 9,000 caterpillars to raise one nest full of babies.

3:19

Study after study shows native plants support thirty-five times more caterpillar life than non-native plants. This gap determines whether birds can successfully raise a family in our neighborhoods.

3:42

Now for the solution. You don’t need a PhD in botany. It’s about picking plants that are true ecosystem players. Let’s look at a few native superstars.

3:58

First, the serviceberry. In early spring, its flowers feed pollinators. Its leaves feed over 120 caterpillar species. Then in June, it produces nutritious berries for more than forty bird species.

4:26

You don’t need to rip up your garden. You can transform it into a thriving habitat with a simple three-step plan. Step one, create layers. Plant ground covers, shrubs, and trees because birds feed at different heights.

4:53

Step two, stop using pesticides. The insects are the food. What looks like leaf damage is actually a working food web. Step three, aim for seventy percent native plants.

5:22

This number comes from research at the University of Delaware. Carolina chickadees could only maintain their population and raise young in yards with at least seventy percent native plants. Below that, nesting success dropped dramatically.

5:38

This is about changing how we see our outdoor spaces. A few chewed leaves are not failure. They are a sign your garden is alive. Caterpillars get a meal, and baby birds get a meal too.

6:11

Leaving leaves on flower beds over winter provides habitat for insects. Leaving seed heads on coneflowers gives finches winter food. This isn’t laziness. It’s being a good host.

6:32

Your messy garden is a five-star all-inclusive resort for wildlife. A single yard can make a difference, and neighborhoods making these changes could create green corridors of habitat.

6:55

We could turn sterile lawns into a vibrant network, essentially a series of backyard national parks. Just imagine what that world would look and sound like.

Why Native Spring Flowers Outperform Non-Native Ornamentals

The superiority of native plants for bird attraction stems from millions of years of coevolution. Research published in Conservation Biology found that suburban properties landscaped entirely with native plants supported significantly more caterpillars and caterpillar species, and bird species of regional conservation concern were about eight times more abundant and diverse on those native‑plant properties compared with conventional landscapes.

When non-native plants dominate landscapes, local insects often cannot digest them, creating what ecologists call “ecological traps” that provide visual abundance but nutritional scarcity. Research published by Doug Tallamy shows that native oaks can support more than 530 species of butterfly and moth caterpillars, while an invasive butterfly bush typically supports only one species, making native plant selection critical for feeding nesting birds.

The timing of native plant emergence also synchronizes perfectly with bird migration and nesting cycles. Native flowers evolved to bloom precisely when arriving migrants need maximum nectar and when breeding birds require peak insect availability for nestlings. This phenological matching means native gardens provide optimal resources during the 6-8 week window when most songbirds are raising young.

In my own yard, after converting approximately 65% to natives over three seasons, I observed a noticeable increase in warbler species during spring migration, with birds spending significantly more time foraging rather than just passing through.

Top Native Spring Flowers by Region

Regional variation matters significantly when selecting native plants. What attracts cardinals in Kentucky may differ from plants that draw chickadees in Maine. The following recommendations are organized by major ecological regions, based on data from native plant societies and university extension research.

Monthly Spring Planting & Bloom Calendar

| Month | Eastern/Midwest | Southeastern | Western | Bird Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February | Prepare beds, order plants | Plant bare-root trees/shrubs | Start seeds indoors | Early migrants arrive (bluebirds, robins) |

| March | Plant bare-root perennials | Wild columbine, Carolina jessamine bloom | Parry’s penstemon blooms | Waterfowl peak, early warblers |

| April | Wild columbine, serviceberry bloom | Coral honeysuckle begins | Rocky Mountain penstemon | Peak migration begins |

| May | Purple coneflower, Virginia bluebells | Crossvine peak bloom | Desert marigold peak | Warbler wave, peak diversity |

| June | Serviceberry fruit ripens | Passionflower blooms | California fuchsia planting | Nesting peak, fledglings |

Eastern and Midwestern Native Spring Flowers

Wild Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

Blooming from April through June, wild columbine produces red and yellow tubular flowers specifically adapted for ruby-throated hummingbird pollination. According to Audubon Great Lakes, many nectar-loving birds pass through in early May as the flowers emerge, making early bloomers like wild columbine critical resources. Research shows that, Aquilegia canadensis blooms in mid‑spring to early summer and produces nectar perfectly timed for migrating hummingbirds, often serving as one of the first nectar sources available in the season.

The plant’s architectural structure also benefits ground-foraging birds. Wild columbine grows 12-24 inches tall with delicate, fernlike foliage that allows light penetration to the forest floor, supporting understory insect populations that thrushes, towhees, and sparrows consume. Native to every eastern state from Maine to Georgia, wild columbine thrives in partial shade with well-drained soil.

Planting Specifications:

- Best time: March-April or September-October

- Spacing: 12-18 inches apart

- Light: Part shade to full sun

- Bloom period: April-June (60-75 days)

- Height: 12-24 inches

Serviceberry (Amelanchier species)

Serviceberry provides triple value through flowers, fruit, and insects. These native shrubs bloom in early April, producing white flower clusters that attract early-emerging native bees. The subsequent dark purple fruits ripen in June, just as songbirds are feeding nestlings.

Research from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service shows that orioles and other nectar-feeding birds are particularly attracted to native flowering trees and shrubs that bloom between May 3–15. The foliage supports over 120 species of lepidopteran larvae, making serviceberry a keystone plant for insectivorous birds like warblers, vireos, and flycatchers.

According to Maryland DNR, the fruits are eaten by at least 40 bird species, including thrushes, orioles and waxwings, providing valuable summer nutrition. They are especially nutritious, giving parent birds quick energy for dozens of daily trips to feed nestlings.

Planting Specifications:

- Best time: March-April or October-November

- Spacing: 15-20 feet apart (tree forms), 6-10 feet (shrub forms)

- Light: Full sun to part shade

- Bloom period: Early April (10-14 days)

- Fruit ripening: Mid to late June

Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Purple Coneflower bridges spring and summer blooming periods, flowering from late May through September. While technically a summer bloomer, late May flowering coincides with peak spring bird diversity, and the extended bloom period provides continuous resources through fall migration. The large purple-pink flowers with prominent central cones attract specialized long-tongued bees while producing abundant seed that finches consume throughout fall and winter.

According to University of Illinois Extension research, purple coneflower supports diverse native bee populations and provides high-quality seeds that American goldfinches particularly favor. Research on its ecological role shows that its flowers are visited by a variety of native bees and other insects, including bumblebees, leaf-cutting bees, and solitary bees that collect pollen and nectar.

Goldfinches time their nesting to coincide with late summer seed production from native plants like coneflowers, using both the seeds as food and the fluffy seedhead material as nest lining. The dried seed heads persist through winter, offering food during resource-scarce periods when other natural foods have been depleted.

Purple coneflower grows 2-4 feet tall in full sun to light shade, tolerating various soil types including clay. Once established, plants require no supplemental water in most regions, making them exceptionally low-maintenance. Deadheading spent blooms encourages continued flowering, but leaving some seed heads provides bird food. Plants self-sow moderately, creating natural-looking drifts without becoming weedy.

Virginia Bluebells (Mertensia virginica)

Virginia bluebells carpet eastern woodlands with sky-blue flowers from April through May, creating nectar resources during a critical gap period. This ephemeral perennial emerges in March, blooms for 3-4 weeks, then goes dormant by midsummer, making it ideal for planting beneath deciduous trees.

The tubular flowers specifically attract long-tongued pollinators including bumblebees and hummingbirds. While Virginia bluebells provide limited direct food for birds, the massive insect activity they generate creates rich hunting grounds for warblers, vireos, and flycatchers passing through during spring migration.

Black Cherry (Prunus serotina)

Native black cherry trees support 456 species of caterpillars according to Tallamy’s research, providing exceptional insect biomass during breeding season. The white flower clusters bloom in May, attracting pollinators, while the dark fruits ripen in June-July when parent birds are feeding fledglings.

Learn more about attracting orioles and other spring migrants through strategic native plant selection.

Southeastern Native Spring Flowers

Coral Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

Coral honeysuckle provides superior nectar for southeastern hummingbirds while avoiding the invasive problems of Asian honeysuckle species. This native vine produces tubular red-orange flowers from April through September, with peak blooming in May precisely when ruby-throated hummingbirds establish breeding territories.

According to research on hummingbird pollination by UC Agriculture and Natural Resources, hummingbirds may visit between 1,000 and 2,000 flowers per day to meet their intense energy needs. These flowers produce abundant nectar with sugar levels well suited to hummingbird metabolism. Unlike invasive bush honeysuckles, coral honeysuckle also produces fruit that thrushes and catbirds can safely eat without spreading aggressively.

Planting Specifications:

- Best time: March-May or September-October

- Light: Full sun to partial shade

- Bloom period: April-September (peak May-June)

- Growth: Twining vine to 10-20 feet

Carolina Jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens)

Carolina jessamine blankets southeastern forests with bright yellow tubular flowers from February through April, providing early-season nectar when few other plants bloom. This evergreen vine serves as a critical early resource for ruby-throated hummingbirds arriving from Central America, often blooming 4-6 weeks before non-native ornamentals.

The vine’s dense evergreen foliage provides year-round cover for birds, with nesting observed by Carolina wrens and blue-gray gnatcatchers. Native from Virginia to Texas, it tolerates various soil types but performs best with consistent moisture during establishment.

Crossvine (Bignonia capreolata)

Crossvine produces clusters of reddish-orange tubular flowers in April and May, specifically attracting ruby-throated hummingbirds. The evergreen foliage turns purple-bronze in winter, providing year-round visual interest and shelter. Native from Maryland to Florida and west to Missouri, crossvine tolerates various light conditions from full sun to moderate shade.

Red Buckeye (Aesculus pavia)

Red buckeye blooms in March-April with tubular red flowers that hummingbirds favor. This small native tree (15-20 feet) provides early nectar before most other plants bloom, giving arriving hummingbirds immediate food sources. The large seeds feed squirrels, which in turn support raptors.

For additional hummingbird strategies, explore best flowering plants to attract hummingbirds.

Western Native Spring Flowers

Penstemon Species

Penstemon species dominate western native gardens with over 250 species adapted to various elevations and moisture conditions. These tubular-flowered perennials bloom from April through July depending on species and elevation, providing consistent nectar for western hummingbird species including broad-tailed, rufous, calliope, and Anna’s hummingbirds. Different regions host different penstemon species, making it essential to select locally native options.

Native Penstemon species produce tubular, nectar-rich flowers that attract hummingbirds. According to Audubon, Parry’s penstemon (P. parryi) blooms March–May with bright pink flowers, while Rocky Mountain penstemon (P. strictus) blooms June–August with deep purple-blue flowers, creating complementary bloom periods. Western gardens that incorporate 3–5 different penstemon species can provide continuous nectar throughout the entire spring migration, supporting hummingbirds from their March arrival through June territory establishment.

California Fuchsia (Epilobium canum)

California fuchsia bridges the critical late-summer nectar gap, flowering July through October. While blooming after spring migration concludes, establishing plants in spring ensures mature specimens bloom abundantly by fall, supporting the complete annual hummingbird cycle. The bright red tubular flowers provide nectar that rufous and Allen’s hummingbirds depend on during fall migration.

Desert Marigold (Baileya multiradiata)

Desert marigold provides year-round color in southwestern deserts, blooming most heavily March through May with sporadic flowering throughout the year. The bright yellow daisy-like flowers attract numerous native bee and fly species that verdins, bushtits, and other small desert birds consume.

Manzanita (Arctostaphylos species)

Multiple manzanita species native to western regions produce urn-shaped pink or white flowers in late winter through early spring (February-April). These drought-tolerant shrubs provide critical early nectar for Anna’s hummingbirds, which breed earlier than other hummingbird species. The dense branching structure also provides nesting sites for various songbirds.

The Critical 70% Native Plant Threshold

Understanding the quantitative relationship between native plants and bird success changes how we approach landscaping. University of Delaware researchers tracked Carolina chickadee reproduction across 150 residential properties, discovering a sharp threshold effect: when native plant biomass dropped below 70% of total landscaping, chickadee reproductive success plummeted to near zero.

This threshold applies broadly across insectivorous species. The mechanism relates to caterpillar availability, as chickadees require approximately 6,000-9,000 caterpillars to raise a single brood. Native plants support robust caterpillar populations, while non-native ornamentals stand nearly devoid of these critical food sources.

For gardeners serious about attracting spring birds, this finding establishes a clear target: convert at least 70% of landscaping to regionally native species. This doesn’t mean eliminating all non-natives immediately, but rather systematically replacing them with natives over 2-3 years.

Calculating Your Current Native Plant Percentage

- Measure total landscaping square footage (exclude hardscape)

- Identify all plants by species

- Verify which species are native to your specific ecoregion

- Calculate approximate coverage for each native plant

- Divide total native coverage by total landscaping area

If the result is below 70%, prioritize adding natives when installing spring flowers.

Spring Planting Timeline for Maximum Bird Attraction

Strategic timing aligns plant installation with bird migration chronology, ensuring resources are available precisely when birds need them.

February-March: Early Preparation

Plant bare-root trees and shrubs while dormant. This window allows plants to establish root systems before energy demands of leaf-out and flowering. Priority species include serviceberry, black cherry, and native oaks for eastern regions; manzanita and native cherries for western regions.

Late March-April: Container Plantings

Install container-grown perennials and wildflowers. Focus on early bloomers like wild columbine, Virginia bluebells, and western penstemons. These establish quickly and may bloom the first season, providing immediate resources for arriving migrants.

May: Final Additions

Complete spring planting with warm-season species. This represents the final opportunity before summer heat stress. Monitor which bird species visit which plants, documenting preferences to inform next season’s additions.

Planting Strategies for Maximum Bird Attraction

Beyond species selection, placement and design strategies determine whether birds discover and utilize spring flowers.

Create Layered Vegetation Structure

Birds occupy different vertical zones. Ground-foraging species like thrushes require low-growing plants and leaf litter. Mid-level foragers including warblers hunt in shrubs 3-8 feet tall. Canopy species like tanagers feed above 15 feet. Successful gardens incorporate flowers at all three levels.

Plant native flowers in drifts of 5-15 individuals rather than isolated specimens. Research shows birds investigate grouped plantings more readily because insect populations concentrate in these areas.

Provide Water Near Flowering Plants

Water sources dramatically increase both species diversity and visitation rates. Position birdbaths within 50 feet of flowering plants, as birds typically forage near water. Adding drippers or fountains increases discovery through sound.

For water feature strategies, see how to attract birds to bird baths.

Eliminate Pesticides Completely

Pesticides kill the arthropods that flowering plants support and birds consume. Even “targeted” applications affect non-target beneficial insects. Accept that native plants with insects on them are functioning correctly—those insects are precisely what attracts birds.

Common Mistakes When Planting for Spring Birds

Mistake 1: Planting Non-Native “Butterfly Plants”

Marketing convinces gardeners that butterfly bush and similar non-natives attract birds because they attract butterflies. However, these plants provide nectar for adult butterflies but don’t support caterpillar populations because local butterfly species cannot lay eggs on non-native plants. Birds need caterpillars, not adult butterflies.

Mistake 2: Installing Plants Inappropriate for Your Region

“Native to North America” doesn’t mean native to your specific region. Plants from other regions often fail to support local insect populations even when they survive. Use plants native to your ecoregion specifically.

Mistake 3: Expecting Instant Results

Native plant gardens require 2-3 years to mature and attract maximum bird diversity. First-year plantings focus energy on root establishment. By the third year, mature plants support substantial insect communities that birds utilize consistently.

Mistake 4: Excessive Spring Cleanup

Cutting back all perennials and removing leaf litter in March eliminates overwintering insect populations that emerge precisely when spring migrants need maximum food availability. Leave stems standing until late April and allow leaf litter to remain beneath plants.

Regional Timing Variations

Spring plant bloom periods and bird migration timing vary significantly by region, requiring location-specific strategies.

Eastern and Midwestern Spring Timing

- Early bloomers: March 15-April 15 (wild columbine, serviceberry, Virginia bluebells)

- Peak migration: April 20-May 20 (warbler wave)

- Late bloomers: May 15-June 15 (native roses, elderberry)

Southeastern Spring Timing

- Early bloomers: February 15-March 31 (Carolina jessamine, red buckeye)

- Peak migration: April 1-May 10 (hummingbirds, tanagers)

- Extended bloom: Many species flower through early summer

Western Spring Timing

- Desert regions: March 1-April 30 (peak before extreme heat)

- Mountain regions: May 1-June 30 (elevation-dependent)

- Coastal regions: April 1-June 15 (moderated by ocean influence)

Learn about spring migration timing to coordinate planting with bird arrival.

Success Metrics: Measuring Effectiveness

Track specific indicators to assess whether plant selections translate into actual bird attraction.

Short-Term Indicators (Weeks 1-4)

- Number of species investigating flowers

- Duration of visits (increased time suggests suitable habitat)

- Specific foraging behaviors (nectar feeding, insect gleaning)

Mid-Season Indicators (Months 2-3)

- Species diversity increase

- Repeated visits by same individuals

- Territorial behaviors suggesting breeding

Long-Term Success (Year 2-3)

- Increased bird density year-over-year

- Nesting attempts in adjacent areas

- Return of same species annually

Top Native Plants Birds Use in Spring (Infographic)

Below is a quick visual summary of the top native plants birds rely on during spring for food, shelter, and nesting support.

Conclusion

Attracting spring birds through strategic plant selection requires understanding that birds need functional ecosystems, not ornamental displays. The 70% native plant threshold, established through peer-reviewed research, provides a clear target that dramatically increases chances of attracting diverse species during migration and breeding.

Implementation doesn’t require perfection. Starting with achievable goals, converting 20-30% of landscaping to natives initially, and building toward the 70% threshold over 2-3 years creates steady progress. Each additional native spring flower, each invasive species removed, and each pesticide application avoided increments habitat quality.

For those serious about attracting spring birds, plant selection represents annual commitment rather than one-time effort. Observation and adaptation based on what works in your specific location refines strategies over time. The reward appears in increasingly diverse bird communities visiting yards specifically for the resources only native flowering plants provide.