If you have ever stared at a pair of finches wondering if you have a breeding pair or just roommates, you are not alone. Learning how to identify male and female finches is not always as simple as spotting the brighter bird. While many assume the bright one is always the male, research in PLOS ONE on Darwin’s finches reveals that 44% of birds show unclear sex-related morphology. This leads even experienced ornithologists to a 13% error rate when they rely on visual traits alone.

Whether you are a backyard birder or a hobbyist breeder, this guide moves beyond basic plumage to provide 100% accurate ID profiles. By combining physical markers, behavioral fingerprints, and seasonal shifts, you will learn to identify gender through song frequency, beak physiology, and wing-bar placement even when visual clues fail.

- The 44% Rule: Bright color is not a guarantee; many species look identical.

- Physical Markers: Males often have redder beaks and bolder breast bars.

- The Diet Factor: Poor nutrition can make a genetic male look female.

- The Song Rule: In identical species, only males sing structured songs.

- Juvenile Mimicry: Young males resemble females until their 90-day molt.

- Behavioral Cues: Males carry nesting material; females tuck eggs.

- Advanced ID: DNA sexing or pelvic exams give full certainty.

Visual Guide: Expert Tips for Identifying Finch Genders Accurately

Identifying these subtle physical markers is easier when you see them in motion. Watch the expert breakdown below for a step-by-step visual guide on how to distinguish male and female finches across several common species:

Show Transcript:

0:00 All right, welcome! Have you ever looked out at your backyard bird feeder and seen a couple of finches and wondered, “Are those a breeding pair of finches, or just two birds sharing the same seed?” Today, we’re going to solve one of nature’s most common, yet surprisingly tricky birdwatching challenges: identifying male and female finches in your garden or backyard.

0:20 This question confuses even experienced birders. One study on Darwin’s finches found that nearly 44% of individuals had physical traits that made their sex identification unclear. Even professional ornithologists have a 13% error rate when guessing a finch’s sex based on appearance alone. So if you’ve been confused, you’re in very good company.

0:42 To accurately identify male vs female finches, we need to look beyond the obvious. We’ll start with common visual clues and then explore the lesser-known signs that can reliably distinguish finch sexes in your backyard.

1:00 The key concept is sexual dimorphism in birds, which refers to visible physical differences between males and females of the same species. Think of it as nature’s color coding system for male and female birds.

1:20 Take the zebra finch as an example. The male has a vibrant red beak, bright orange cheek patches, and distinct barred patterns on the sides. The female has a softer orange beak and muted gray plumage. Easy, right? Not always.

1:46 While color is often the first clue, it’s not always reliable. Diet can drastically affect feather coloration—a phenomenon called the carotenoid factor. In birds like the house finch, red feathers come from pigments in their bird food, called carotenoids. If a male eats a poor diet while growing new feathers, he may appear dull yellow—almost identical to a female—even though he’s fully capable of singing and breeding.

2:41 Since color alone can be misleading, we need additional visual identification tips. For zebra finches, look for red vs orange beaks and barred flanks. For American goldfinches, males have jet-black wing feathers, while females have brown wings. Using multiple visual clues increases your accuracy in finch sex identification.

3:14 But appearance isn’t everything. Behavior is often the strongest clue. Male finches sing structured, repeated songs—a nearly foolproof way to identify them. Watch for courtship behaviors, which are exclusive to males:

- Straw display: carrying grass to show nest-building skills.

- Vertical hopping: energetic bouncing while singing.

- Tail fanning: spreading feathers to appear larger and more impressive.

4:01 Nesting roles offer more insights. The male is usually the architect, bringing materials and building the nest. The female is the interior designer, arranging the inside and developing a brood patch—a bare spot on her belly used to incubate eggs.

4:25 For species where males and females look identical, you need expert-level identification methods:

- DNA sexing of birds: 100% accurate for any age.

- Pelvic bone spacing: wider in females ready to lay eggs.

- Cloacal protuberance: a swelling present in breeding males.

4:57 Let’s bust two common myths about backyard finches:

- Aggression myth: The most aggressive finch at the feeder is not always male; dominant females can be very assertive, especially near nesting.

- Size myth: Bigger birds aren’t always male. Natural size variation exists in all finch species.

5:22 Your finch identification toolkit is complete. The key takeaway: there’s no single magic sign. The best approach is threefold: look, listen, and watch.

5:38 Start with visual clues: feather color, beak shape, and markings. Then listen for finch songs, which are the most reliable male indicators. Finally, observe behavior: courtship displays and nesting roles. Combining all these clues ensures accurate male vs female finch identification in your backyard or garden.

5:59 Now that you know these finch identification secrets, what will you notice differently in your own backyard birdwatching? Start observing today and become a confident finch expert!

The Quick-Look Checklist: Sexual Dimorphism vs. Monomorphism

The Dimorphism Rule: Why the Brighter Bird Is Not Always Male

Sexual dimorphism (visible differences between males and females) occurs when evolutionary pressures favor different appearances in each sex. Males of most dimorphic finch species display brighter colors, more elaborate markings, or larger ornamental features than females. This pattern reflects sexual selection pressures where females choose mates based on plumage quality that signals male health, genetic fitness, and foraging ability.

However, dimorphism varies dramatically among species and even within species depending on subspecies, mutations, and seasonal timing. Zebra finches exhibit obvious dimorphism. Males possess orange cheek patches, barred flanks, and red beaks, while females show none of these features and have orange beaks.

House finches demonstrate variable dimorphism. According to research on male mate choice in house finches, while males display colorful plumage ranging from red to yellow and females are generally drab brown, some females have a subdued version of the same pattern of ornamental coloration seen in males.

The carotenoid factor further complicates house finch identification. According to research on proximate basis of variation in carotenoid pigmentation, male house finches vary in plumage color from pale yellow to bright red, with coloration determined by dietary carotenoid access during molt.

Males fed carotenoid-deficient diets grew pale yellow feathers indistinguishable from female plumage, while those fed canthaxanthin-supplemented diets grew bright red feathers. This means a dull yellow male may appear identical to a female despite being genetically male and capable of singing and breeding.

Monomorphic Species: Identification Strategies for Identical-Looking Birds

Monomorphic species present the greatest identification challenge. Society finches (Lonchura striata domestica), owl finches (Taeniopygia bichenovii), and spice finches (Lonchura punctulata) show no reliable plumage differences between sexes. Both males and females display identical colors, patterns, and beak coloration regardless of age or breeding condition.

For these species, behavioral observation becomes critical. Only males sing structured songs. Males perform courtship displays including vertical hopping, tail-fanning, and bowing. Males carry nesting material to potential sites while females enter boxes to evaluate interior dimensions. Watching for these behaviors over several days provides more reliable sexing than any single physical characteristic.

Advanced methods offer certainty when behavior remains ambiguous. DNA sexing through blood or feather samples provides 100% accuracy regardless of species, age, or plumage. The pelvic bone test (described in detail later) works for sexually mature females, whose pelvic bones spread to accommodate egg passage. These methods prove essential for breeders establishing pairs in monomorphic species where visual identification fails completely.

The Juvenile Trap: Why Young Males Mimic Female Plumage

According to research on sex identification in Darwin’s finches, juveniles of sexually dimorphic species look alike until they molt into adult-like plumage and beak coloration. This extends through the first several months of life in most species, creating an identification void where sex determination proves impossible through visual assessment alone.

The 90-day transition represents the approximate period when young males of dimorphic species begin showing sex-specific traits. In zebra finches, males develop orange cheek patches and breast bars around 60-90 days post-fledging. American goldfinch males require a full year, retaining olive-brown juvenile plumage through their first winter before molting into yellow breeding plumage the following spring.

Behavioral cues emerge earlier than plumage in many species. Young male zebra finches begin practicing subsong (quiet, rambling vocalizations) as early as 30 days old, weeks before developing adult male plumage. Close listening reveals these practice sessions despite juvenile appearing identical to females. The early song behavior provides the first reliable sexing method while plumage remains unhelpful.

Expert Species-Specific Identification Guide

| Finch Species | Male Identification Markers | Female Identification Markers | Best ID Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebra Finch | Red coral beak, orange cheek patches, black breast bar, and chestnut spotted flanks. | Orange beak, no cheek patches, no breast bar, and plain gray-brown flanks. | Visual (Plumage/Beak) |

| Gouldian Finch | Deep purple (violet) breast, intense head color, and extensive blue face border. | Pale purple (lavender) breast, narrower head color, and ivory beak with blue tip. | Visual (Breast Color) |

| Society Finch | Identical plumage to female; only males perform structured songs and vertical hopping. | Identical plumage to male; evaluates nest interior dimensions and performs “egg-tucking” . | Behavioral (Song/Nesting) |

| House Finch | “Raspberry dip” red/orange plumage on crown and breast; sings and courts. | Uniform brown-and-white streaking; no trace of red, orange, or yellow color. | Visual (Color) |

| Java Rice Finch | Larger, bulbous black head cap; thicker, robust beak; more pink orbital skin. | Smaller, flatter head cap; thinner, more delicate beak; less extensive pink orbital skin. | Physical (Head Shape) / Song |

Physical Identification: Beyond Bright Colors

Beak Color Nuances: The Red vs. Orange Shift in Zebra Finches

Zebra finch beak coloration provides one of the most reliable sexing characteristics in commonly kept finches. According to research on zebra finch sexual dimorphism, males have red beaks while females have orange beaks. However, the distinction proves more nuanced than simple red versus orange categorization.

Male beak color ranges from bright coral-red to deep brick-red depending on age, health, and hormonal status. The redness intensifies during breeding condition when testosterone levels peak. Non-breeding males show slightly duller red that could be mistaken for dark orange in poor lighting.

Female beak color spans pale peach-orange to medium orange. Young females display the palest beaks, darkening slightly with maturity. The key diagnostic feature is not absolute color but rather the absence of red tones. Female beaks never show the coral or brick-red characteristic of males regardless of age, condition, or lighting.

Mutations complicate beak-based sexing in some color varieties. Fawn zebra finches show reduced melanin affecting both plumage and beak pigmentation. In these birds, male beaks appear light coral while female beaks become very pale peach, maintaining the relative difference but shifted toward paler tones overall.

Wing and Tail Markers: Decoding Black vs. Brown Flight Feathers

American goldfinches demonstrate wing-based sexual dimorphism visible year-round despite dramatic seasonal plumage changes. Males in all plumage phases show blacker wings with more contrasting white wing bars than females. The wing coverts and flight feathers on males appear jet-black while females show dark brown to grayish-brown wings.

The difference becomes most obvious in breeding plumage when males transform to brilliant yellow bodies. The jet-black wings create stark contrast against yellow plumage. Females in summer plumage show olive-yellow bodies with brown wings, creating much softer overall appearance with less contrast.

Winter plumage eliminates body color differences. Both sexes molt into buffy-brown non-breeding plumage. Wings remain the primary identification feature. Hold birds in good lighting and examine wing covert color. True black indicates male. Dark brown indicates female. The distinction proves subtle but consistent across all ages and seasons.

Breast Bars and Flank Spots: Precise Counting in Zebra and Owl Finches

Male zebra finches possess a black breast bar stretching horizontally across the upper chest. This bar varies in width from thin striping to broad bands depending on individual variation and genetic background. Females completely lack breast bars. Any bird showing even a faint dark line across the chest is male.

Flank markings provide additional confirmation. Males show chestnut flanks with white spots creating distinctive polka-dotted appearance along the sides. The spotting pattern varies between 6-12 clear white dots per flank in most individuals. Females have unmarked pale gray-brown flanks without spots or chestnut coloration.

Owl finches show subtle breast markings requiring closer inspection. Males often display slightly bolder, more contrasting black-and-white barring across the breast and flanks. Females show softer, less distinct barring. The difference proves marginal, making owl finches one of the more challenging dimorphic species for visual sexing based on plumage alone.

Behavioral Fingerprinting: High Information Gain Methods

The Song Difference: Why Only Males Sing

According to research on zebra finch behavior, males sing and females do not. This represents the single most reliable behavioral sex diagnostic across the vast majority of finch species. Male song serves courtship and territorial functions, driven by testosterone and controlled by specialized neural structures that develop only in males.

Song definition matters for accurate identification. True song consists of structured sequences of notes repeated in stereotyped patterns. Males learn these patterns during a critical period in youth, practicing through months of subsong before crystallizing into adult song form. The structured, repeated nature distinguishes true song from simple contact calls both sexes produce.

According to research on sexual dimorphism of the zebra finch syrinx, male songs range from low-frequency sounds (480-1200 Hz) with rich upper harmonic content to more tonal high-frequency sounds (3-7 kHz), while female distance calls contain only low frequency components and less pronounced frequency modulation than males.

Rare exceptions exist. In some individuals, females produce song-like vocalizations through hormonal abnormalities or experimental testosterone treatment. These cases remain vanishingly uncommon in wild populations. For practical identification purposes, any finch producing structured, repeated song is male with near-complete certainty.

Courtship Rituals: Identifying the Straw-Display and Vertical Hopping

Male finches perform elaborate courtship displays to attract females and stimulate pair bonding. The straw-display occurs when males carry nesting material (grass, straw, feathers) in their beaks while performing exaggerated hopping motions near females. The behavior signals nest-building capability and parental investment potential.

Vertical hopping represents another male-specific courtship behavior. Males bounce up and down rapidly while singing, often puffing chest feathers and spreading tail feathers to maximize visual display. The hopping intensity increases when females show interest, with males bouncing progressively higher and faster.

Tail-fanning displays occur across multiple species. Males spread tail feathers into full fan configuration while swaying side to side and singing. The fanned tail reveals the full extent of tail markings and overall body size, providing females with maximum visual information for mate assessment.

Bowing displays involve males lowering their heads and bodies toward perches while singing and puffing feathers. The submissive-appearing posture paradoxically signals dominance and breeding readiness. Females rarely bow, and when they do, the behavior lacks the exaggerated feather-puffing and synchronized song characteristic of male displays.

Nesting Roles: Structure Building vs. Egg-Tucking

Division of nesting labor differs between species but generally follows patterns where males focus on structural construction while females handle interior arrangement and egg management. In zebra finches, according to research on their breeding behavior, males build the nest while females lay eggs and both parents take turns incubating.

Males gather and transport the majority of nesting material during initial construction phases. They make dozens of trips carrying grass, hay, feathers, and string to the nest site. Females participate in material transport but at lower rates, focusing more on arranging material inside the nest structure.

The egg-tuck behavior provides definitive female identification when observed. Only females perform the specialized movements involved in positioning eggs within the nest cup. They use beak and feet to roll eggs into optimal positions, turn them for even incubation temperature, and adjust them when sitting down to brood.

Incubation patch development confirms female sex in many species. Females develop a bare patch of skin on the abdomen where feathers fall out during breeding season. This brood patch allows direct skin-to-egg contact for efficient heat transfer. Males in most species do not develop brood patches even when they share incubation duties.

Vocal Frequency Analysis: Distance Call Pitch in Bengalese Finches

Distance calls differ between sexes in frequency characteristics even in species where both sexes vocalize. Bengalese finches (also called society finches) demonstrate this pattern despite being monomorphic in plumage. Male distance calls average lower in fundamental frequency than female distance calls due to sexual dimorphism in syrinx anatomy.

Spectrographic analysis reveals the differences. Male calls center around 2-3 kHz while female calls peak around 3-4 kHz. The difference proves subtle to human hearing but becomes obvious when analyzed with audio software showing frequency spectrograms. The technique works best with multiple recorded samples from known individuals to establish baseline frequency ranges.

Call rate provides additional clues. Males vocalize more frequently than females in most contexts. During separation from mates, males produce distance calls every 5-15 seconds while females call every 30-60 seconds. The heightened male call rate reflects testosterone-driven motivation to maintain vocal contact and advertise presence.

Seasonal and Diet Wildcards

Breeding vs. Eclipse Plumage: Temporary Brilliance

Strawberry finches (red avadavats) and orange weavers demonstrate dramatic seasonal plumage changes where males transform from drab eclipse plumage identical to females into brilliant breeding colors. The transformation occurs through complete body molt triggered by lengthening day length and hormonal changes.

Male strawberry finches in eclipse plumage show brown bodies with subtle spotting, appearing virtually identical to females. During breeding season, males molt into brilliant red plumage with white spotting creating jewel-like appearance. The transformation requires 6-8 weeks of feather replacement, with birds showing mixed plumage during the transition period.

Eclipse plumage creates identification challenges during non-breeding months (typically fall through early spring). Birds that appear female-like may include actual females plus males in eclipse plumage. Behavioral observation becomes essential. Birds performing song, courtship displays, or aggressive territoriality despite female-like plumage are males in eclipse. True females never sing regardless of season.

The Carotenoid Factor: How Diet Creates Dull Males

Male house finches demonstrate the most dramatic diet-based plumage variation of any commonly observed species. According to research on proximate basis of carotenoid pigmentation, captive males fed carotenoid-deficient diets grew pale yellow feathers while those fed canthaxanthin-supplemented diets grew bright red feathers. The dietary influence on plumage color creates scenarios where males appear indistinguishable from females based on color alone.

The mechanism involves carotenoid metabolism. Birds cannot synthesize carotenoids de novo. They must ingest yellow dietary carotenoids and metabolically convert them to red pigments deposited in growing feathers. According to research on dietary carotenoids and plumage, males that ingested food with higher concentrations of carotenoid pigments grew brighter ornamental plumage.

Males experiencing poor nutrition, illness, or limited access to carotenoid-rich foods during molt produce yellow or orange plumage rather than red. These dull males are genetically and behaviorally male (they sing, court females, and breed successfully) but lack the red coloration associated with high-quality males. Identification requires attending to behavior, song, and facial markings rather than relying solely on body color.

American goldfinches show similar though less dramatic dietary effects. Captive birds fed low-carotenoid diets produce paler yellow breeding plumage than wild birds. The effect proves less confusing than in house finches because goldfinch females never show yellow plumage, so even pale-yellow males remain distinguishable from olive females.

Hormonal Cues: Beak Color Changes During Breeding

Female zebra finches demonstrate beak color darkening during breeding condition. The normally pale orange beak deepens to darker orange or orange-red as estrogen levels rise during egg-laying cycles. The color change reverses after breeding ceases, with beaks lightening back to pale orange during non-breeding periods.

The timing provides practical utility for breeding management. Females showing darkened beak color are approaching or actively in breeding condition, making them suitable for pairing with males. Females with very pale beaks are not in breeding condition and are unlikely to accept male courtship or lay fertile eggs even if paired.

Males show minimal seasonal beak color variation. The red beak of adult males maintains relatively consistent intensity year-round regardless of breeding condition. This sexual difference in beak color plasticity means that seasonal beak changes provide female-specific information rather than affecting both sexes equally.

Advanced Scientific and Physiological Methods

The Cloacal Protuberance: Physical Anatomy Checks

Male finches in breeding condition develop a cloacal protuberance, a visible swelling of the cloaca caused by enlargement of the seminal glomerulus (sperm storage structure). The protuberance appears as a distinct bulge ventral to the tail base, easily visible when birds are examined in-hand.

The structure develops rapidly when males enter breeding condition, reaching maximum size within 1-2 weeks of hormonal changes. The swelling remains prominent throughout the breeding season, then regresses when breeding ceases. Outside breeding season, male and female cloacae appear similar, eliminating this diagnostic feature during non-breeding months.

Examination technique requires gentle handling. Hold the bird securely and blow gently on the vent area to part feathers and reveal the cloaca. A prominent rounded swelling indicates breeding-condition male. Flat or minimally swollen cloaca indicates either female or non-breeding male. The method works best when combined with breeding-season timing and other sex characteristics.

DNA Sexing Protocols: 100% Certainty Through Genetics

DNA sexing analyzes the CHD gene (chromodomain helicase DNA binding gene) located on sex chromosomes. According to research on molecular sexing of Darwin’s finches, PCR-based sexing using CHD1 gene primers successfully determined sex in all 29 tested embryos of six species, providing accurate results from embryos through adults.

The method works because birds have ZZ (male) and ZW (female) sex chromosome systems. The CHD gene exists in slightly different forms on the Z and W chromosomes. PCR amplification produces two bands for females (one from Z, one from W) and one band for males (two copies from ZZ). The band pattern definitively identifies genetic sex regardless of age, plumage, or season.

Sample collection requires either blood (1-2 drops) or freshly plucked feathers (3-5 contour feathers with follicle material attached). Commercial labs process samples for $15-25 per bird with results typically available within one week. The investment proves worthwhile for valuable breeding birds, rare species, or situations where behavioral observation remains inconclusive.

Accuracy approaches 100% when proper sample collection and handling procedures are followed. The few errors that occur result from sample contamination or degradation rather than test limitations. DNA sexing provides the gold standard for finch sex determination, particularly valuable for monomorphic species, juveniles, and birds in ambiguous plumage states.

The Pelvic Bone Test: Finger Spacing for Egg-Laying Females

Sexually mature females develop increased distance between pelvic bones to accommodate egg passage. The pelvic bones (pubic bones) spread from nearly touching in immature birds to finger-width apart in laying females. The widening results from hormonal softening of connective tissue allowing bone movement.

Testing technique involves gentle palpation. Hold the bird ventral-side up and locate the pelvic bones on either side of the cloaca. Place fingertips on the bone tips and assess spacing. Bones less than 5mm apart indicate male or immature female. Bones 8-10mm apart indicate sexually mature female. Intermediate spacing suggests female approaching maturity or recently out of breeding condition.

Accuracy depends on bird size, handler experience, and female breeding status. In small finches (zebra, society, spice finches), the absolute distance remains small even in mature females, requiring careful assessment. Large finches (Gouldian, Java rice finches) show more obvious spacing differences. The method works best on females actively breeding or recently breeding rather than those long out of condition.

Limitations include inability to sex males definitively (narrow spacing could indicate male or immature female) and ineffectiveness on very young birds regardless of sex. The test serves best as confirmatory evidence combined with other identification methods rather than standalone diagnostic.

Expert Cheat Sheet by Popular Species

Zebra Finches: Beak Hue, Cheek Patches, and Throat Stripes

Males: Red coral beak, orange cheek patches, black-and-white barred throat, black breast bar, chestnut flanks with white spots. Females: Orange beak, no cheek patches, no throat barring, no breast bar, plain gray-brown flanks.

Primary identification: Cheek patches provide instant male identification. Any bird with orange cheek patches is male without exception. Secondary identification: Beak color (red vs. orange) confirms sex when viewed in good lighting. Tertiary identification: Breast bar and flank spots provide additional male-specific markers when cheek patches are obscured.

Mutation complications: White zebra finches lack all pattern elements in both sexes. Sex these birds through beak color (red = male, orange = female) and behavior (song, courtship displays). Fawn mutations show reduced melanin affecting beak intensity but maintaining relative male/female differences.

Gouldian Finches: Head Rings, Breast Depth, and Blue Beak-Tip Indicators

Males: Broader, more intense head color (red, black, or yellow depending on morph), deeper purple breast color, more extensive blue face border. Females: Narrower, paler head color, lighter purple (nearly lavender) breast, less extensive blue face border.

The breast color difference provides the most reliable visual cue. Males show rich purple approaching violet. Females show pale purple to lavender. The contrast becomes obvious when male and female perch side-by-side but proves challenging with isolated individuals lacking direct comparison.

Beak color subtleties: Both sexes have ivory beaks with blue tips during breeding condition. Males show slightly more extensive blue coloration and more intense blue saturation. The difference proves too subtle for reliable sexing except in side-by-side comparison of known birds.

House and Purple Finches: Raspberry Dip vs. Forehead Streaks

House finch males: Variable coloration from yellow through orange to red focused on crown, throat, breast, and rump. Red males show “raspberry dip” appearance where red color looks like the bird was dipped in red paint. Brown streaking on flanks and belly regardless of red intensity.

House finch females: Brown-and-white streaked overall with no trace of red, orange, or yellow coloration. Streaking extends uniformly across body without color contrast. Slightly smaller than males on average but overlap makes size unreliable for individual identification.

Purple finch males: More extensive raspberry-red coloration covering most of head and breast. Less contrast between red areas and streaked areas compared to house finches. Unstreaked undertail coverts (white or pale pink without brown streaking).

Purple finch females: Crisp white eyebrow stripe providing strong facial pattern. Heavily streaked brown-and-white body similar to house finch females but with stronger facial contrast. Unstreaked undertail coverts matching males.

Java Rice Finches: Head Cap Width and Swelling

Males: Larger, more bulbous head cap with black crown extending lower on sides of head. More extensive pink orbital skin surrounding eyes. Thicker, heavier beak appearing more robust in profile. Broader body overall though size overlap makes this unreliable alone.

Females: Smaller, flatter head cap with black crown stopping higher on sides of head. Less extensive pink orbital skin. Thinner, more delicate beak profile. Overall appearance of lighter, more refined head structure.

The head cap difference provides best visual diagnostic but requires experience and ideally side-by-side comparison. Photography helps by allowing detailed examination and comparison impossible during brief in-person observation. Song remains definitive (only males produce loud, complex song).

Troubleshooting Common Identification Myths

The Aggression Myth: Why Dominant Females Act Like Males

Aggression levels correlate poorly with sex in finches. Dominant females frequently display aggressive behaviors including chasing, feather-pulling, and resource guarding traditionally associated with males. The confusion arises because testosterone correlates with both maleness and aggression in mammals, leading to assumptions that aggression indicates maleness in birds.

Avian endocrinology differs from mammalian patterns. Female finches produce significant testosterone during breeding season to facilitate aggressive nest defense and territory maintenance. This female testosterone production can equal or exceed non-breeding male levels, producing female aggression rivaling or exceeding male aggression in specific contexts.

Practical implications: Never sex finches based solely on aggressive behavior. The most aggressive bird in an aviary could be female. Combine behavioral observation with physical characteristics, song production, and breeding behaviors for accurate identification. Aggression indicates social dominance within a specific group, not biological sex.

The Size Fallacy: Why Body Mass Is the Least Reliable Indicator

Male finches average slightly larger than females across most species, leading to assumptions that the larger bird in a pair is male. However, individual variation and measurement error make size-based sexing highly unreliable except in side-by-side comparison of known birds.

According to research on Darwin’s finches, males average slightly larger in body and bill size than females, but overlap between sexes makes individual identification based on size alone prone to significant error. A large female may exceed a small male in all measurements despite sex differences in population averages.

Weight provides even less reliability than linear measurements. Individual birds fluctuate in weight by 10-15% daily based on feeding, time of day, and stress. Reproductive state affects female weight dramatically as egg development adds grams immediately before laying. These fluctuations exceed between-sex differences, making weight useless for individual sex determination.

Size-based sexing works only when evaluating population-level patterns with known birds or when combining size with other characteristics. For instance, a large bird with red plumage and song is definitely male. A small bird lacking red plumage and never singing is probably female. Size alone provides no definitive information.

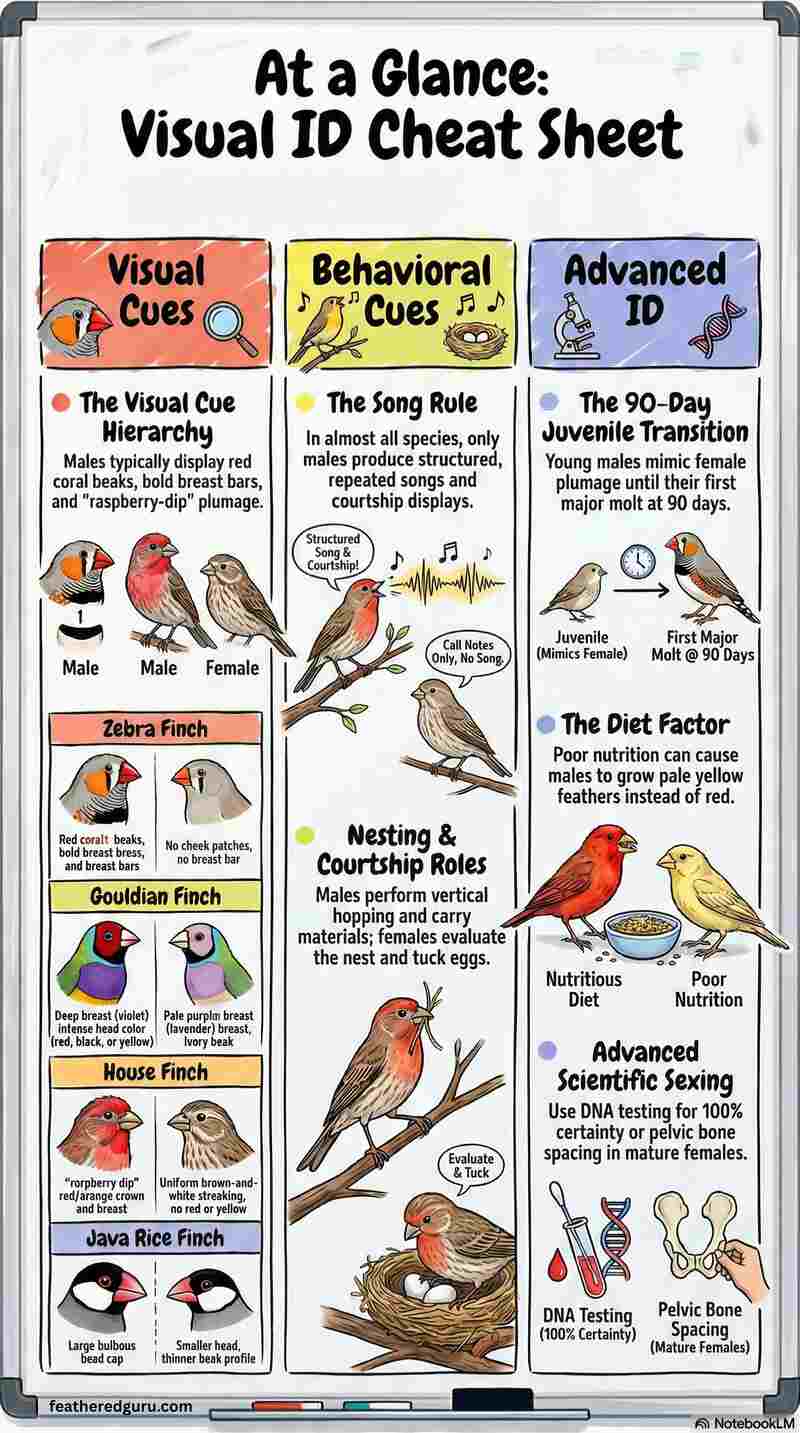

At a Glance: Visual ID Cheat Sheet

Before you go, use this visual cheat sheet to quickly recap the most reliable physical and behavioral markers we’ve covered. It’s the perfect ‘pocket guide’ for the next time you’re observing your birds in the aviary!

Frequently Asked Questions: Mastering Finch Sex Identification

Is the brightest finch always the male?

Not necessarily. While many species show sexual dimorphism where males are brighter, research shows that up to 44% of finches have unclear physical traits. Factors like a low-carotenoid diet can cause a genetic male to appear as a dull yellow, making him nearly indistinguishable from a female.

What is the most reliable way to identify a male finch?

The “Song Rule” is the most reliable behavioral indicator. In almost all finch species, only the males sing structured, repeated songs to attract mates or defend territory. Observing courtship behaviors like vertical hopping or carrying nesting material (the straw display) also confirms a male.

How can I tell the sex of finches that look identical?

For monomorphic species like Society or Owl finches, you must rely on behavioral fingerprinting or professional methods. Expert techniques include DNA sexing (100% accurate), checking for a cloacal protuberance in breeding males, or measuring pelvic bone spacing in mature females.

Conclusion: Mastering Finch Sex Identification

Accurate finch sex identification requires integrating multiple information sources rather than relying on single characteristics. Physical markers provide starting points. Beak color, cheek patches, breast bars, and wing patterns offer immediate visual cues in dimorphic species. However, seasonal plumage changes, dietary effects on carotenoid coloration, mutations eliminating pattern elements, and monomorphic species all create scenarios where visual identification fails or misleads.

Behavioral observation fills gaps where plumage falls short. Song production identifies males definitively across nearly all species regardless of plumage state. Courtship displays, nesting roles, and breeding-season anatomical changes provide sex-specific information when observed carefully over time. The investment in behavioral observation pays dividends through reliable identification even in challenging species and age classes.

Advanced methods provide certainty when observation remains inconclusive. DNA sexing eliminates all ambiguity regardless of species, age, or plumage. The pelvic bone test confirms breeding-condition females. Cloacal examination reveals breeding-condition males. These hands-on techniques supplement rather than replace behavioral and visual observation.

The progression from novice to expert identification involves moving beyond simplistic “bright = male” assumptions to nuanced understanding of species-specific patterns, seasonal variation, and behavioral indicators. Practice with known birds builds the pattern-recognition skills needed for rapid, accurate field identification. Photograph uncertain birds for later comparison. Record vocalizations for spectral analysis. Document behaviors over multiple observation sessions.

For additional information on finch care and breeding, explore guides on attracting wild finches to your yard, distinguishing house finches from purple finches, and understanding finch nesting behavior. Learning about seasonal finch diet changes and native plants that support finch populations provides ecological context that enhances identification skills by revealing how behavior and appearance reflect evolutionary adaptations to specific environmental pressures.