Summer birdwatching demands different timing strategies than other seasons due to heat stress, altered activity patterns, and nesting behaviors that change when and how birds move through residential landscapes. The best times of day to see birds in your garden in summer depend on temperature, species behavior, and breeding activity, making timing just as important as where you watch. Knowing when birds are most active helps you plan your outings and catch the highest levels of movement and song.

Breeding season activity reaches a peak for most species during the hour centered at sunrise or shortly after, then gradually slows as the morning progresses and temperatures rise. Understanding how temperature, time of day, and species-specific behaviors interact during summer months allows birdwatchers to maximize observation opportunities while minimizing disturbance during this sensitive season 🙂.

- Early morning, 30 min before sunrise to 9:00 AM, is peak activity.

- Morning activity comes from feeding nestlings, singing, and defending territory.

- Midday activity drops due to heat, predators, and satiety.

- Water and shade attract birds during midday inactivity.

- Late afternoon and early evening show a smaller activity peak.

- Hummingbirds, raptors, and waterbirds often stay active midday.

- Extreme heat limits activity to dawn and dusk hours.

- Early summer is peak breeding; mid-summer has fledglings; late summer is dispersal.

- Adjust timing by temperature, weather, and species for best results.

Why Birds Visit Gardens at Certain Times in Summer

This short explainer walks through typical summer bird activity from early morning to evening.

Show Transcript:

0:00

Summer bird watching is amazing, right? But it’s a completely different game compared to the other seasons. The real secret isn’t just where you look, it’s when you look.

0:10

Once that summer heat kicks in, timing becomes everything. You know the feeling. At dawn, your backyard is buzzing with songs and fluttering wings.

0:19

Then by noon, it’s dead silent. It’s like the birds vanished into thin air. So where did they all go?

0:31

It’s not random at all. That disappearing act is actually a finely tuned survival strategy. Birds follow a strict daily schedule to beat the heat.

0:43

And if you can crack that schedule, that’s the key to winning at summer bird watching.

0:51

So let’s jump straight into the prime time. This is the main event of any summer day for bird watchers. This is when nearly all the action happens.

1:02

You can see an entire bird’s summer routine in one simple rhythm. There’s a huge burst of activity in the early morning, a sharp drop at midday, and a smaller comeback in the evening.

1:16

This pattern is the foundation of summer birding. So why the crazy morning rush? It comes down to a few urgent needs.

1:24

First, they’re hungry. Birds have been fasting all night and need to refuel fast. Second, males are busy singing and defending territory. That’s the dawn chorus we all love.

1:36

And maybe most important, they’re feeding babies. Raising young takes thousands of insects every single day.

1:45

This isn’t just a theory. The US Geological Survey analyzed over a million bird surveys and confirmed it. The science is clear.

1:55

The absolute peak of bird activity happens within the first one to two hours around sunrise.

2:02

Here’s a great pro tip from ornithologist David Sibley. If you want to hear the dawn chorus, you need to be out before sunrise.

2:11

But if you want to actually see birds in good light, the hour after sunrise is your best window. It’s a small difference, but it matters.

2:23

Once the morning rush ends, the sun climbs high and everything goes quiet. So let’s talk about why birds disappear every single day.

2:33

It comes down to one word: thermoregulation. That’s just a scientific way of saying birds have to manage their body temperature.

2:41

Unlike us, birds are basically wearing a down jacket all day long. In summer, their biggest challenge isn’t staying warm. It’s staying cool.

2:52

There’s a tipping point where heat becomes dangerous. Research from NASA found that when air temperatures reach 104 degrees Fahrenheit, songbirds are forced to start panting.

3:07

Panting cools them down, but it also causes rapid water loss. Without access to water, birds can die from dehydration in just a few hours.

3:18

That midday retreat isn’t laziness. It’s a life-or-death survival move.

3:25

That said, the skies aren’t completely empty. Hawks and falcons often soar on rising heat currents. Hummingbirds keep feeding nonstop due to their intense metabolism.

3:41

And birds near ponds or lakes will stay active around water sources.

3:47

As the heat eases later in the day, we get a short encore. Evening activity returns, but it’s brief and much quieter than the morning.

3:58

This time is mostly about grabbing one last meal before nightfall. You’ll usually see activity pick up around 4:00 p.m.

4:10

But here’s the key detail. Everything winds down about thirty minutes before sunset. By the time you’re enjoying the sunset, most songbirds are already settled in.

4:27

Now that we understand the daily rhythm, how do we use this to improve summer bird watching? It comes down to four simple rules.

4:39

Number one, get up early. The window from before sunrise until about 9:00 a.m. is non-negotiable.

4:45

Number two, add water. A bird bath acts like an oasis and attracts birds all day, even in extreme heat.

4:53

Number three, watch the weather. Cooler or cloudy mornings can extend bird activity longer than usual.

5:00

And number four, adapt during heat waves. That means starting even earlier than normal.

5:07

Remember, summer isn’t static. Early summer is about nesting and territory, with lots of singing and nest visits.

5:16

By midsummer, fledglings take over. It gets noisy as young birds beg and follow their parents.

5:24

Late summer is quieter, but it brings surprises as young birds wander and show up in new places.

5:30

All of this leads to one big question. Research shows birds in hot regions are starting their days earlier and earlier to cope with rising temperatures.

5:41

As the planet warms, will the morning activity window keep shrinking? Will birds be forced into a frantic race against sunrise just to survive?

5:52

It’s a sobering thought, and it connects what we see in our backyards to a much bigger story.

The Dawn Peak: Early Morning Excellence

Early morning represents the single most productive period for summer birdwatching across virtually all songbird species. According to research published by the U.S. Geological Survey analyzing more than a million Breeding Bird Survey stops, breeding season activity reaches a peak for most species during the hour centered at sunrise or in the following hour, then declines gradually as the morning progresses.

Research consistently demonstrates that bird activity concentrates in the hours immediately surrounding sunrise, with this pattern intensifying during breeding season.

The Science of Morning Activity

This morning peak stems from multiple biological imperatives. Birds emerge from overnight fasting eager to replenish energy reserves. Territorial males sing vigorously to establish and defend breeding territories. Parent birds begin the exhausting work of finding enough insects to feed hungry nestlings, requiring thousands of caterpillars daily for successful brood-rearing.

The USGS research found that activity patterns for a given species remain quite constant from year to year. Each species demonstrates its own characteristic pattern, though considerable similarity exists among members of the same genus.

Temperature plays a crucial role in morning activity levels. According to research published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, desert birds in the Arava Desert began and terminated their daily activity within a 45-minute window around morning and evening civil twilights. Significantly, the birds advanced the onset of daily activity in response to rising ambient heat, starting earlier on hotter days to maximize cooler foraging time.

Optimal Morning Viewing Window

For maximum bird diversity and activity, arrive at viewing locations 30 minutes before sunrise and plan to remain for 2-3 hours. The period from 30 minutes before sunrise until approximately 9:00 AM captures peak activity for most species, though this window shifts earlier as temperatures rise through summer.

According to ornithologist David Sibley writing in BirdWatching magazine, while the dawn chorus beginning at first light creates one of nature’s greatest experiences, it’s not actually the best time to see birds. The surge of birdsong peaking before sunrise involves birds singing from concealed perches in darkness or dim light. For visual observation, the hour following sunrise provides better lighting while maintaining high activity levels.

The morning feeding frenzy reflects urgent biological needs. Parent birds must locate food quickly to feed nestlings before temperatures rise. Research documents that many species make dozens to hundreds of feeding trips daily, with this activity concentrated in morning hours when insects are most accessible and temperatures remain manageable.

For those interested in photographing garden birds, early morning provides the best combination of good light, high activity, and birds willing to perch in open locations while singing or foraging.

The Midday Lull: Understanding Reduced Activity

As morning progresses into midday, bird activity drops dramatically across most species and habitats. This reduction stems from multiple factors including temperature stress, satiation, and predator avoidance.

Temperature-Driven Behavioral Changes

According to Georgia Department of Natural Resources research, birds become far less vocal and active during the heat of the day compared to cooler morning hours. Restricting activity when temperatures peak reduces the amount of heat their bodies produce and reduces their need for water, both critical considerations during summer’s hottest periods.

Research published in PLOS ONE on little bustards found that temperature, time of day, and date explained variation in display behavior, with birds displaying significantly less during higher temperatures. The model predicted an average decrease in daytime display activity of up to 10.4% for temperature increases projected by 2100, demonstrating how heat directly suppresses bird activity.

Midday represents the period when thermoregulation demands override other behaviors. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, many birds avoid the sun by limiting daytime activity, foraging in early morning, evening, or throughout the night to conserve energy and rest during the warmest times of day.

Species and Habitat Variations

While activity generally reaches a low point in midday according to USGS research, patterns vary by habitat and species. In deciduous forests, activity of many species continues at a reduced rate rather than ceasing entirely. Desert habitats see activity almost completely stop during peak heat, while common backyard birds in shaded residential areas maintain some movement through midday.

Water features become critically important during midday lulls. According to Georgia DNR observations, bird feeders stocked with seed see little activity at midday during summer, but a shady place with water can provide excellent birding right through the afternoon. For detailed guidance on water feature placement, see our article on how to keep birds hydrated during summer.

The reduced midday activity also reflects satiation. According to research on daily foraging patterns published in PMC, birds generally started to feed before sunrise and continued to forage at a steady to increasing rate throughout the day, with foraging in most species terminating well before sunset. This suggests birds reach required energy reserve levels before day’s end, allowing midday rest periods.

Making the Most of Midday

While midday offers reduced songbird activity, certain species remain active and observable. Raptors including hawks and falcons become more visible during late morning and early afternoon. According to birding references, hawks take advantage of rising thermals created by ground heating, allowing effortless soaring while scanning for prey below.

Hummingbirds maintain activity throughout the day, visiting feeders and flowers regardless of temperature. Their high metabolism demands constant feeding, making them reliable midday subjects for observation. For those interested in these remarkable birds, our guide on how to attract hummingbirds provides comprehensive strategies.

Waterbirds continue feeding regardless of temperature, making ponds, lakes, and wetland edges productive midday locations when woodland birds have gone quiet.

Late Afternoon and Evening: The Secondary Peak

As temperatures begin cooling in late afternoon, bird activity increases again, though never matching morning levels. This secondary peak provides valuable observation opportunities for those unable to bird in early morning.

The Evening Activity Increase

According to Sibley writing in BirdWatching magazine, while morning is generally when birdwatchers see the most birds, late afternoon can show a slight increase in activity as daily temperatures start cooling. However, the level of activity varies with weather, temperature, season, and species, and the amount of bird activity in late afternoon or evening never matches what morning provides.

The USGS research on breeding season activity found that while morning peaks are consistent and pronounced, afternoon patterns are more variable. Some species show modest evening increases while others remain relatively inactive until roosting time.

Evening activity serves different purposes than morning foraging. According to research, birds look for their last meals with remaining daylight, bolster their nests, and make preparations for the night ahead. This final feeding bout ensures adequate energy reserves for overnight fasting.

Optimal Evening Timing

For late afternoon and evening birdwatching, plan viewing from approximately 4:00 PM until 30 minutes before sunset. This window captures the cooling-temperature activity increase while providing adequate light for observation.

According to Sibley, many songbirds call it a day and go to roost long before sunset, so evening viewing windows close earlier than many birdwatchers expect. Species differ dramatically in roosting times, with some retiring to cover while others remain active nearly until dark.

Evening observations require different expectations than morning watches. Bird diversity typically decreases, vocalizations reduce compared to morning levels, and many species have already settled into roosting areas. However, for those interested in observing nest-related behaviors, evening provides opportunities to watch birds returning to nest sites or engaging in final feeding runs.

For gardens where nesting birds are active, evening hours require care to avoid disturbance. Parent birds making final food deliveries to nestlings should not be interrupted, and observers should maintain greater distances than during non-breeding seasons.

Species-Specific Activity Patterns

While general patterns of morning peaks and midday lulls apply broadly, individual species demonstrate characteristic activity timing that birdwatchers can exploit for targeted observation.

Early Risers

According to the USGS research, each species has its own characteristic activity pattern, with much similarity among members of the same genus. Some species consistently begin activity earlier than others, creating opportunities for focused early-morning observation.

Thrushes, including robins, typically begin singing and foraging in deep twilight before most other species stir. Warblers become active around civil twilight, filling dawn with their varied songs. Sparrows and finches follow shortly after, creating layered waves of activity through the early morning period.

Understanding these patterns allows targeting specific species. Birders seeking warblers should arrive before sunrise, while those interested in chickadees or titmice can arrive slightly later without missing peak activity.

Heat-Tolerant Species

Certain species maintain higher midday activity than others, providing reliable observation opportunities when most birds have retreated to shade. Mourning doves, for instance, continue visiting feeding areas and water sources throughout the day despite heat.

According to research, birds differ in their heat tolerance based on size, plumage, behavior, and habitat preferences. Smaller birds with higher surface-area-to-volume ratios face greater challenges maintaining body temperature in heat, typically showing more pronounced midday inactivity than larger species.

Evening Specialists

While most songbirds reduce activity well before sunset, certain species specialize in evening and twilight foraging. Common nighthawks become active at dusk, swooping through the air catching insects. Chimney swifts maintain high activity until nearly dark, their chattering calls filling the evening sky.

These crepuscular species represent different observation opportunities requiring awareness of their specific timing. Missing the narrow window when they’re active means missing them entirely for the day.

Temperature Thresholds and Behavioral Shifts

Research demonstrates that specific temperature thresholds trigger dramatic behavioral changes that fundamentally alter when and how birds can be observed.

Critical Temperature Points

According to NASA research on desert songbirds, at about 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit), songbirds start panting, which increases the rate of water loss very rapidly. Most animals can tolerate water losses resulting in 15 or 20 percent loss of body mass before they die, meaning an animal experiencing peak temperatures during a hot summer day with no access to water will not survive more than a few hours.

This physiological reality forces birds to prioritize thermoregulation over all other activities when temperatures approach or exceed 104°F. Observation opportunities plummet during extreme heat events as birds seek shade and minimize movement.

Research analyzing eBird data published by NASA found that immediately following extreme weather, certain birds were observed less frequently than following normal weather conditions. Year-round residents or short-distance migrants like Carolina Chickadees were present less often following a week of extreme heat, particularly at the edges of their range.

Adaptive Timing Adjustments

The research on Arabian babblers in the Arava Desert found that birds advanced the onset of daily activity by 8.8 minutes during the study period as temperatures increased, demonstrating behavioral plasticity in response to warming conditions. However, birds never became active in complete darkness, constrained by the need for adequate light for foraging.

This suggests that as climate change drives higher summer temperatures, morning activity windows may continue shifting earlier while evening windows extend later, with midday inactivity periods lengthening. Birdwatchers should adjust timing earlier in the morning and later in the evening during heat waves to capture peak activity.

Weather-Dependent Flexibility

According to references, wet and windy weather can deter bird activity, while mild and pleasant conditions encourage it. The best days for birdwatching feature mild temperatures and little to no wind. Rainy days can lead to increased activity once weather clears, creating typical activity bursts.

Cloud cover moderates temperature extremes, potentially extending morning and evening activity windows while reducing the depth of midday lulls. Overcast summer days may show more consistent activity throughout the day compared to bright, hot conditions that drive pronounced peaks and troughs.

Practical Strategies for Summer Birdwatching

Maximizing summer birdwatching success requires adapting strategies to accommodate heat effects and altered activity patterns.

Prioritizing Morning Hours

Given research consistently demonstrating morning supremacy, serious birdwatchers should prioritize early outings whenever possible. The effort of early rising pays dividends through dramatically higher bird counts, greater species diversity, and better observation conditions.

Plan to arrive at viewing locations before sunrise during summer months. Bring a flashlight for navigating in pre-dawn darkness. Position yourself near known bird congregation points like water features, fruiting native plants, or areas with high insect activity to maximize early encounters.

Understanding when birds start nesting in spring helps time observation efforts to coincide with peak breeding activity when birds are most conspicuous and active.

Creating All-Day Opportunities

While natural bird activity decreases at midday, strategic habitat features maintain observation opportunities throughout the day. Water sources attract birds continuously during summer heat, providing reliable viewing regardless of the hour.

Shaded areas with diverse native plantings support greater midday activity than exposed locations. The combination of thermal relief and insect availability keeps some birds active when open areas see complete abandonment.

For comprehensive guidance on creating productive habitat, see our article on bird-friendly garden design, which addresses how multi-layer vegetation structures create microclimates that support activity throughout the day.

Evening Contingency Planning

For those unable to bird in mornings due to work or other commitments, evening watches provide secondary opportunities. While activity levels don’t match morning peaks, late afternoon and early evening offer reasonable observation potential.

Focus evening efforts on water features, which see concentrated activity as birds make final hydration stops before roosting. Position near known nest sites to observe parent birds’ final feeding trips. Target species known for extended activity periods rather than early-retiring species.

Heat Wave Adjustments

During extreme heat events, modify timing even more aggressively toward the margins of the day. Arrive well before sunrise to capture the brief period before temperatures soar. Consider evening watches starting later, as birds may delay activity until temperatures drop substantially.

On days exceeding 95°F, midday observation becomes largely unproductive for songbirds. Use these periods for equipment maintenance, data organization, or studying field guides rather than active field time.

Seasonal Progression Through Summer

Summer encompasses a long period with changing bird behaviors as the season progresses from early breeding through fledgling care and into post-breeding dispersal.

Early Summer: Peak Breeding Activity

June represents peak breeding season for most temperate songbirds, with nesting activity driving the most pronounced dawn peaks and midday lulls. Parent birds make maximum feeding trips during early morning hours, creating the season’s best observation opportunities.

Early summer also sees the highest levels of territorial singing, with males proclaiming territories and attracting mates through dawn chorus participation. This vocal activity makes species identification easier and birds more conspicuous.

Mid-Summer: Fledgling Period

July brings fledglings out of nests, creating different observation opportunities. Young birds remain relatively sedentary and noisy, begging constantly for food while perched in visible locations. Parent birds continue intensive feeding but over more extended periods as multiple fledglings demand attention.

Activity patterns may spread more evenly through the day during fledgling care, as parents can’t meet food demands within compressed time windows. This can improve midday observation compared to the peak nesting period.

Late Summer: Post-Breeding Dispersal

August sees reduced territorial behavior as breeding concludes. Birds become quieter and less conspicuous, making observation more challenging. However, increased movement by both adults and juvenile birds creates opportunities to see species that remained hidden during breeding.

Post-breeding dispersal brings different species into gardens and viewing areas as birds explore beyond natal territories. This can increase diversity if not density of observations.

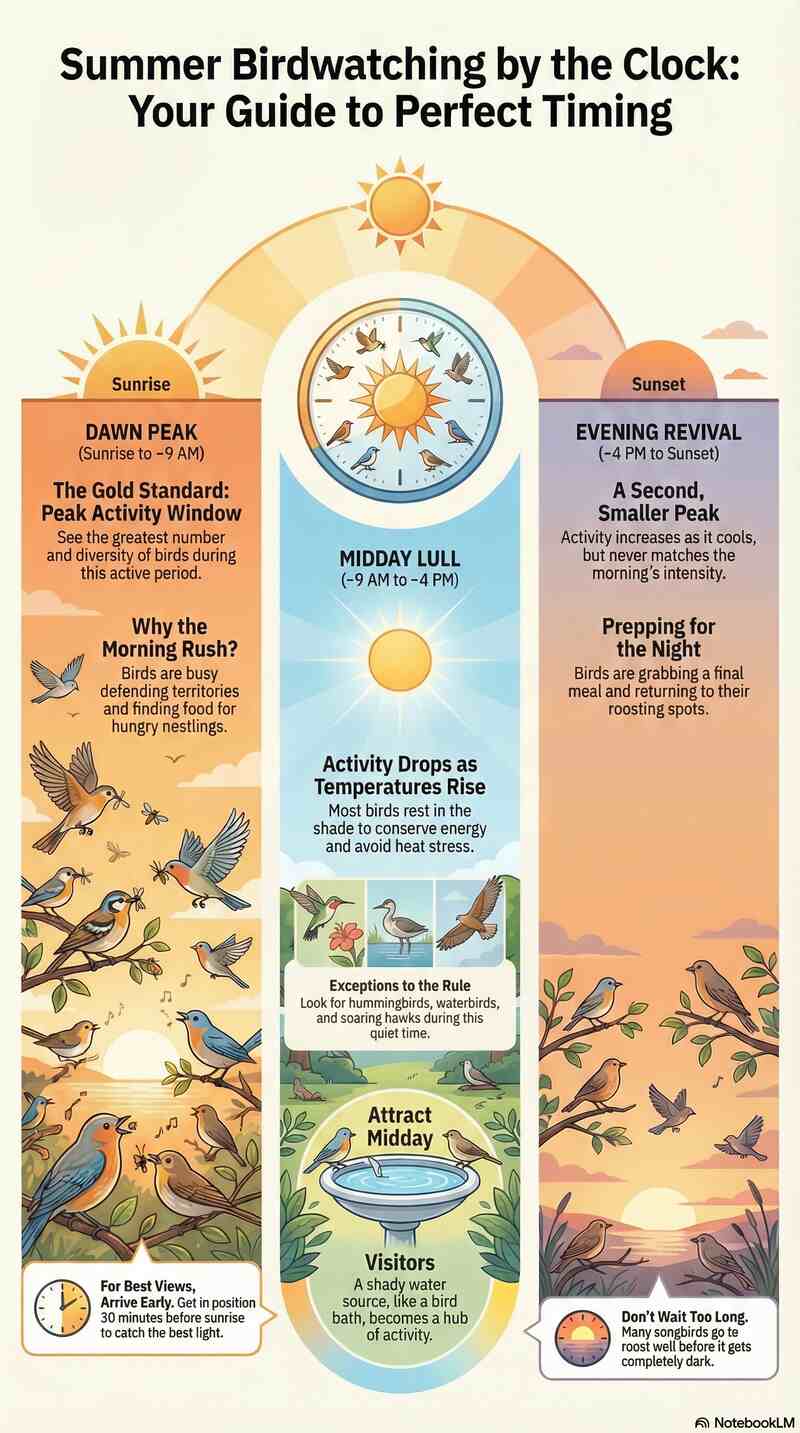

Infographic: Best Times to See Garden Birds in Summer

Conclusion

Summer birdwatching timing demands careful consideration of temperature effects, species-specific patterns, and the constraints imposed by breeding behaviors. Research consistently demonstrates that early morning hours from 30 minutes before sunrise through approximately 9:00 AM provide optimal observation opportunities across most species and conditions. This morning peak reflects urgent biological needs for territory defense, mate attraction, and nestling feeding that concentrate activity in the coolest hours of the day.

Midday periods see dramatic activity reductions as birds prioritize thermoregulation and shade-seeking over foraging and movement, with this effect intensifying as temperatures rise. While certain species including raptors, hummingbirds, and waterbirds maintain midday activity, songbird observation becomes challenging during peak heat hours.

Late afternoon and early evening provide secondary opportunities as temperatures cool, though activity levels never match morning peaks and many species roost well before sunset. Understanding species-specific timing allows targeting particular birds during their characteristic activity windows.

Temperature thresholds drive behavioral shifts that fundamentally alter when birds can be observed, with extreme heat events suppressing activity across most species and compressing remaining activity into increasingly narrow dawn and dusk windows. As climate change drives higher summer temperatures, these patterns will likely intensify, requiring birdwatchers to adjust timing even more aggressively toward the coolest hours of the day.

Successful summer birdwatching requires accepting that early morning dominates observation opportunities, with secondary potential in early evening and specialized midday chances near water or in heavily shaded habitats. This differs markedly from other seasons when activity spreads more evenly throughout the day, reflecting summer’s unique combination of breeding demands and heat stress that concentrate bird activity in the hours when both imperatives can be simultaneously met.