You know that feeling when a tiny bird lands on a branch three feet from your face and just… stares at you? Not with fear, but with this almost judgmental “yeah, I see you” attitude? That’s the black-capped chickadee for you 😏. These pint-sized powerhouses have stolen my heart (and probably some seeds from my neighbor’s feeder), and honestly, once you get to know them, you’ll understand why birders lose their minds over these little fluffballs.

I’ve spent way too many winter mornings watching these birds work my backyard like they own the place, because let’s be real, they kind of do. And the more I learn black-capped chickadee facts, the more impressed I get. These aren’t just cute birds with a catchy name. They’re survival experts, vocal virtuosos, and surprisingly brainy for something that weighs less than half an ounce.

- Tiny birds (0.3-0.5 oz) with black caps, bibs, and white cheeks.

- Found in northern U.S. and Canada; forests, parks, and backyards.

- Eat insects in spring/summer, seeds and berries in fall/winter.

- Hide seeds in hundreds of spots and remember them for months.

- Social, clever, fearless; small flocks with strict hierarchies.

- “Chick-a-dee” call signals predator threat; “fee-bee” is mating song.

- Cavity nesters; females handle incubation and feeding chicks.

- Winter survival: regulated hypothermia, cached seeds, shivering muscles.

- Populations stable; adapt well to human-altered landscapes.

- Control insects and support food chains; key backyard birds.

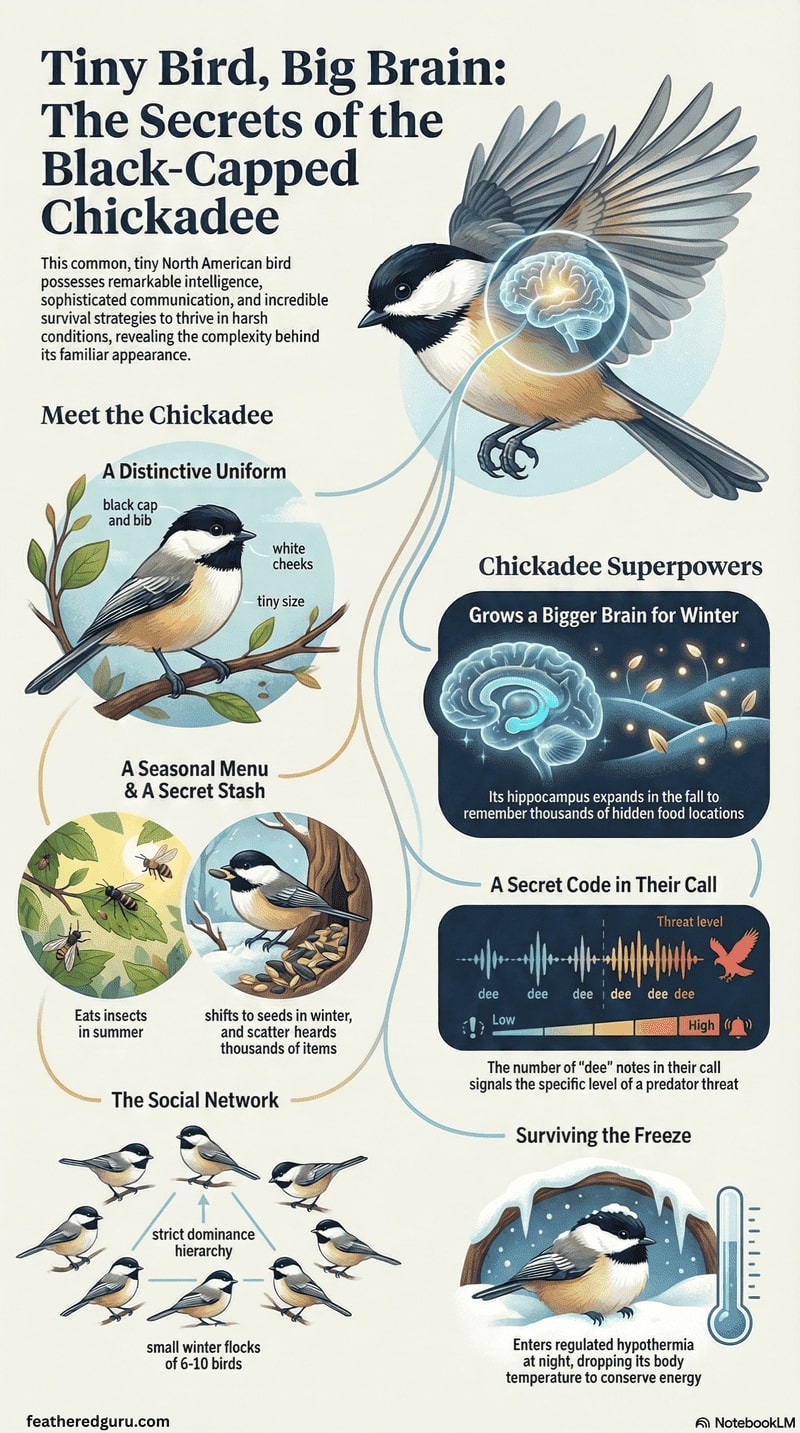

Check the infographic below for a quick visual summary.

Quick Explainer: Black-Capped Chickadee Facts

Want to see these fascinating chickadee facts in action? Watch this quick explainer video to get a closer look at their behavior and features.

Show Transcript

0:00 – 0:28

Okay, you’ve definitely seen this bird a thousand times, but did you know it has a superpowered brain, a complex language, and a social life that could rival a spy thriller? Meet the black-capped chickadee—fearless, tiny, and full of surprises. That look it gives you when it lands nearby? It’s sizing you up, and there’s far more going on behind those feathers than you can imagine.

0:28 – 1:08

So, who is this backyard acrobat? The bold black cap, the matching bib under the chin, and bright white cheeks make them easy to identify. They are tiny acrobats in a feathered marshmallow package. You can find them almost anywhere: dense forests, city parks—basically anywhere with decent trees and a steady food supply. They’re our familiar backyard neighbors.

1:08 – 2:18

But surviving a harsh winter? That’s where the chickadee’s genius shines.

- Flexible diet: In spring and summer, they hunt insects for protein; in winter, they pivot to high-energy seeds and berries.

- Caching strategy: They hide hundreds or even thousands of seeds across their territory and remember every single location.

- Memory power: Their hippocampus grows each fall to store this data—an incredible adaptation for winter survival.

- Cold-weather tricks: Fluffing feathers for insulation, huddling together for warmth, and shivering deliberately to generate heat.

Their brains allow them to access this huge memory bank at just the right moment—pure survival genius.

2:18 – 3:15

Chickadees are also social masterminds. Winter flocks at your feeder aren’t random; they’re structured social units, often with other birds like nuthatches. Every bird knows its place in a strict dominance hierarchy, determining access to food, safety, and sleeping spots.

3:15 – 4:00

Their famous calls are equally sophisticated. What sounds like a simple “chick-a-dee-dee” is actually a complex language:

- Two-note “toot” or “phoebe” song: Used in spring and summer to attract mates and defend territory.

- Chick-a-dee call: An advanced alarm system. A small predator may get just a few “D’s,” while a hawk triggers rapid-fire D’s. The more D’s, the greater the danger—and the forest is listening.

4:00 – 4:48

Recap: incredible memory, complex social structure, and detailed language. But there’s more. Chickadees are problem solvers, figuring out tricky feeders and even recognizing individual humans who refill them. Their brains physically change each year to meet environmental demands—a stunning example of neuroplasticity in action.

4:48 – 5:29

The best part? These brilliant little birds are thriving. Populations are stable, a testament to their adaptability and resilience. Next time you see a chickadee flitting around, don’t just see a cute fluff ball—see a master survivalist, social strategist, and tiny genius. Pause, watch, and marvel at the complex life happening right before your eyes. And remember—they’re probably sizing you up too, and they have every right to.

Black-Capped Chickadee Identification

Here’s the thing about black-capped chickadees: they’re basically wearing a uniform. That bold black cap sitting on top of their head like a tiny beret? Dead giveaway. Pair that with the black bib under their chin, and you’ve got one of the most distinctive little birds in North America.

Their cheeks are bright white, creating this stark contrast that makes them pop even on the grayest winter day. The back and wings show off soft gray tones, while their sides have this peachy-buff wash that adds a touch of warmth to their appearance. They’re about 4.7 to 5.9 inches long, roughly the size of your palm if you’re wondering, and weigh somewhere between 0.3 to 0.5 ounces. Yeah, they’re basically feathered marshmallows.

The tail is relatively long for their body size, which gives them excellent balance when they’re doing their signature move: hanging upside down from branches like tiny acrobats. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, their wing bars and overall plumage pattern remain consistent year-round, making them one of the easier species to identify regardless of season.

One quick tip? If you’re trying to distinguish them from their cousins (looking at you, Carolina chickadee), check the wing feathers. Black-capped chickadees have more white edging on their secondary feathers. It’s subtle, but once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Habitat & Range of Black-Capped Chickadees

Black-capped chickadees aren’t picky, and that’s part of their charm. You’ll find them across the northern United States and Canada, thriving in deciduous and mixed forests, suburban parks, and yes, absolutely raiding your backyard bird feeder.

The black-capped chickadee range stretches from Alaska through Canada and down into the northern tier of U.S. states. We’re talking everywhere from Maine to Oregon, with populations dipping south into the Appalachian Mountains. They love areas with mature trees, especially those with natural cavities or old woodpecker holes where they can nest.

IMO, one of the coolest things about these birds is how adaptable they are. I’ve spotted them in dense coniferous forests and in suburban neighborhoods with nothing but a few oak trees and some overgrown shrubs. They don’t need wilderness; they just need trees and food sources.

During winter, they become even more visible in residential areas because they’re not shy about visiting feeders. Research published in the journal Urban Ecosystems found that black-capped chickadees living in urban environments show altered fear behavior and increased tolerance to humans compared to their rural counterparts, basically, city chickadees have zero chill when it comes to approaching humans for food.

They tend to prefer habitats with a mix of tree species because different trees provide different resources throughout the year. Birch and willow trees attract insects, while conifers offer shelter and some seed sources. According to National Audubon Society, they’re non-migratory in most of their range, though northern populations may move slightly south during particularly harsh winters.

Diet & Feeding Habits

Let’s talk about what keeps these tiny engines running. The black-capped chickadee diet is impressively diverse, which is probably why they’re so successful as a species.

During spring and summer, they’re primarily insectivores. We’re talking caterpillars, spiders, aphids, scale insects, and pretty much any other tiny invertebrate they can find. They’ll meticulously search tree bark, leaves, and branches for hidden insects and their eggs. I’ve watched one spend ten minutes working over a single branch, picking off invisible-to-me bugs with laser focus.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Come fall and winter, their diet shifts dramatically to include more seeds and berries. They love sunflower seeds, pine seeds, and the berries from poison ivy (which, FYI, doesn’t affect them like it affects us, lucky birds). Research from The National Wildlife Federation indicates that during winter months, seeds and other plant material can make up to 50% of their diet.

And get this: chickadees are hoarders. They practice something called scatter-hoarding, where they hide individual seeds in hundreds of different locations throughout their territory. A study published in Nature found that chickadees can remember thousands of hiding spots for extended periods. Their hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for spatial memory, actually grows larger in the fall to accommodate all this information. Yeah, these birds literally grow their brains to remember where they stashed their snacks. If that’s not impressive, I don’t know what is.

At feeders, they’re not the type to sit and munch. They’ll grab a seed, fly off to a nearby branch, hold it with their feet, and hammer it open with their beak. Then they’re back for another. It’s like watching the world’s tiniest, most efficient grocery shopper.

Behavior & Social Life

This is where chickadees really shine. Their behavior is complex, fascinating, and honestly kind of hilarious when you start paying attention.

First off, they’re incredibly social during non-breeding season. They form small flocks, usually consisting of six to ten birds, with a strict dominance hierarchy. The dominant birds get first dibs on food and the best roosting spots. I’ve literally watched chickadees wait their turn at my feeder, with one bird giving way to another without any fuss. It’s surprisingly civilized for something happening in nature.

These flocks often include other small bird species like nuthatches, downy woodpeckers, and tufted titmice. It’s a safety-in-numbers strategy: more eyes watching for predators means everyone has a better chance of survival. When one bird spots danger and sounds the alarm, the whole crew scatters.

Their fearlessness around humans is legendary. During winter, you can sometimes get chickadees to eat from your hand with a little patience. I tried this last February, standing stock-still with sunflower seeds in my palm for what felt like forever. The first time one actually landed on my finger, I nearly scared it off by gasping. Worth it though 🙂

They’re also incredibly curious and investigative. If you hang something new in your yard, a weird decoration, a different feeder, whatever, chickadees will be the first ones checking it out. They’ll investigate thoroughly before deciding whether it’s useful, dangerous, or just boring.

Calls & Vocalizations

Let’s talk about that famous call, because there’s way more going on here than you’d think.

The chickadee vocalizations are actually a sophisticated communication system. That classic “chick-a-dee-dee-dee” call isn’t just them saying hello. The number of “dee” notes at the end communicates information about predator threats. More “dees” means a higher level of threat, it’s literally a predator alarm system with gradations of panic.

A fascinating study published in Science by Christopher Templeton and colleagues found that chickadees add more “dee” notes when faced with smaller, more agile predators like pygmy owls (which can actually catch chickadees) compared to larger, less maneuverable threats. They’re not just screaming “danger!”, they’re providing their flock with specific threat assessment information. That’s remarkably sophisticated for a bird brain.

Then there’s the “fee-bee” song, which is their territorial and mating call. Males sing it to establish breeding territories in late winter and spring. It’s a clear, two-note whistle that sounds like someone slowly saying “hey sweetie.” According to research from Birds of North America Online, the frequency and pitch of this song can vary regionally, meaning chickadees in Maine might have slightly different “dialects” than those in Oregon.

They also have various other calls for different situations: aggressive “gargle” calls during territorial disputes, contact calls to keep flock members in touch, and high-pitched “seet” calls for aerial predators. I’ve heard that last one send my entire backyard into immediate silence, every bird just vanishes. It’s eerie.

Nesting & Reproduction

When spring rolls around, chickadees get down to the serious business of reproduction. Their nesting habits are pretty specific and surprisingly labor-intensive.

They’re cavity nesters, which means they need holes in trees. Sometimes they’ll use old woodpecker cavities, but often they’ll excavate their own nest cavity in soft, rotting wood. Both male and female participate in this construction project, though the female does most of the heavy lifting. They’ll chip away at the wood for up to two weeks, creating a cavity about 7-8 inches deep.

Once the cavity is ready, the female builds the actual nest inside using moss, animal hair, plant fibers, and feathers. She’ll create a soft cup, and I mean soft, these nests are cozy. She typically lays 6-8 eggs, though clutch sizes can range from 1-13 depending on conditions and the female’s health.

The eggs are white with reddish-brown speckles and are tiny, we’re talking about the size of a jelly bean. The female incubates them for about 12-13 days while the male brings her food. Once the chicks hatch, both parents work overtime bringing caterpillars and other insects to feed the hungry babies.

According to the University of Michigan’s Animal Diversity Web, chickadees typically raise one brood per year, with the female incubating eggs for 12-13 days. The young leave the nest after about 16 days, though they’ll stick around with their parents for another few weeks learning essential survival skills.

Here’s something I find oddly touching: chickadee parents will continue feeding their fledglings even after they’ve left the nest, teaching them where to find food and how to crack seeds open. It’s like bird kindergarten.

Winter Survival Strategies

Okay, this is where chickadees go from “cute” to “absolutely incredible.” Their winter survival strategies are nothing short of miraculous when you consider they weigh about as much as three pennies.

First, they enter a state called regulated hypothermia at night. Their body temperature drops by up to 12 degrees Celsius, which significantly reduces their energy expenditure. It’s a controlled process, not true torpor like hummingbirds experience, but impressive nonetheless. This adaptation can reduce their nighttime energy needs by up to 20%.

Remember those food caches I mentioned earlier? Those become critical in winter. Chickadees rely on their stored seeds to supplement their diet when insects are scarce. They’ll visit their cache sites throughout the day, recovering food they hid weeks or even months earlier.

Their feathers provide incredible insulation too. They have about 2,000 feathers covering their tiny bodies, and they fluff them up to trap warm air close to their skin. You’ve probably seen a chickadee looking like a round little puffball on a cold day, that’s them maximizing their insulation.

They also increase their muscle mass before winter, particularly their flight muscles. This extra mass helps generate body heat through shivering thermogenesis. Basically, they shiver to stay warm, and those beefed-up muscles make the process more efficient.

Social roosting is another survival strategy. While they’re territorial during breeding season, in winter, chickadees will sometimes huddle together in tree cavities to conserve heat. Multiple birds sharing body warmth in a confined space can significantly increase survival rates during brutal cold snaps.

Research published in The Condor: Ornithological Applications examined seasonal thermoregulation in black-capped chickadees, finding that winter birds showed a 36% increase in maximal thermogenic capacity compared to summer birds, their bodies literally ramp up their heat-generating abilities when cold weather hits. Evolution in action, folks.

Intelligence & Memory

I mentioned earlier how their hippocampus grows to handle spatial memory, but the cognitive abilities of chickadees extend beyond just remembering where they hid seeds.

Research has shown they can count, or at least perceive numerical differences. They understand social hierarchies and remember which individual birds rank above or below them. They can assess threats and communicate nuanced information about those threats to their flock members.

They also show problem-solving abilities. In laboratory settings, chickadees have learned to open puzzle feeders, pull strings to access food, and even use tools in some experimental scenarios. For a bird with a brain the size of a large pea, that’s remarkable.

What really gets me is how they recognize individual humans. If you regularly feed chickadees in your yard, they absolutely know who you are. They’ll distinguish you from other humans and may even approach you specifically while avoiding others. There are countless stories of chickadees following “their” humans around the yard, waiting for handouts. It’s not just hunger, they’re making individual associations.

Conservation & Threats

Here’s some good news in a world that often feels short on it: black-capped chickadees are doing just fine. Their population is stable, and in some areas, it’s even increasing. They’re listed as a species of “Least Concern” by conservation organizations, which means they’re not facing any immediate threats to their survival.

Their adaptability is their superpower. Unlike many bird species that struggle with habitat loss and climate change, chickadees have proven remarkably resilient. They thrive in both natural and human-altered landscapes, and they’re perfectly happy visiting bird feeders when natural food sources run low.

That said, climate change does pose some interesting challenges for chickadees, particularly regarding their range overlap with Carolina chickadees. As temperatures warm, Carolina chickadees are pushing north, and the two species are interbreeding in areas where their ranges meet. It’s something researchers are keeping an eye on, though it’s not an immediate crisis.

The best thing we can do to support chickadees? Keep mature trees standing when possible, avoid using pesticides that eliminate their insect food sources, and provide supplemental feeding during harsh winter months. They’re not picky, black oil sunflower seeds and suet are chickadee gold.

Why Black-Capped Chickadees Matter

Look, I’ll be honest: there have been some rough winters where watching chickadees at my feeder was genuinely therapeutic. Something about these tiny, resilient birds going about their business in subzero temperatures makes my own problems feel a little more manageable.

But beyond the personal connection, chickadees play important ecological roles. They’re voracious insect eaters during breeding season, helping control populations of caterpillars and other insects that can damage trees. They’re also prey for larger birds and mammals, making them an important link in the food chain.

Their willingness to nest in human-provided nest boxes makes them excellent subjects for citizen science projects. Researchers have learned an enormous amount about bird behavior, cognition, and physiology by studying chickadees, and much of that research has applications for understanding other species too.

Plus, they’re just delightful. In a world that can feel increasingly complicated and heavy, there’s something wonderfully simple about a chickadee. They don’t overthink things. They find food, avoid predators, raise their babies, and somehow manage to look cheerful doing it. Maybe we could all learn something from that approach :/

Visual Recap: Black-Capped Chickadee Facts

Want a quick, at-a-glance summary of everything we’ve covered? Check out this infographic:

Wrapping It Up

Black-capped chickadees are proof that you don’t need to be big or flashy to be remarkable. These tiny birds survive brutal winters, remember thousands of food cache locations, communicate complex information through their calls, and somehow find time to be friendly and curious about the world around them, including the weird humans who stand in their yards with cameras.

The more time I spend watching these birds, the more impressed I become. They’re not just surviving; they’re thriving, adapting to whatever challenges come their way with a resilience that’s genuinely inspiring. Whether you’re a serious birder or someone who just likes watching the action at your backyard feeder, chickadees offer endless entertainment and education.

So next time you hear that familiar “chick-a-dee-dee-dee” call, take a moment to actually watch what’s going on. You might catch them caching seeds for later, working their way through a flock hierarchy, or just hanging upside down from a branch because apparently that’s comfortable for them. These little birds have earned their place as one of North America’s most beloved species, and honestly? They deserve every bit of that affection.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to go refill my feeder. I’m pretty sure the local chickadee mafia is judging me through the window right now.