Every year, various finch species transform from quiet winter residents into the vibrant, song-filled centerpieces of successful native gardening. While many birders rely on feeders for a quick visit, learning how to attract finches with backyard plants is the secret to creating a permanent sanctuary for these diverse birds. This shift from convenience feeding to building a complete ecosystem where finches nest, molt into breeding plumage, and raise young provides a level of specialized nutrition that no tube feeder can replicate.

This guide moves beyond traditional bird feeding to focus exclusively on the botany of finch attraction. You will discover the plant families these birds depend on, including the biological obsession many species have with composite flowers, and how tree catkins ensure winter survival. By following this framework, you create a self-sustaining habitat where finch populations return annually to nest and thrive in an irreplaceable native landscape 😊.

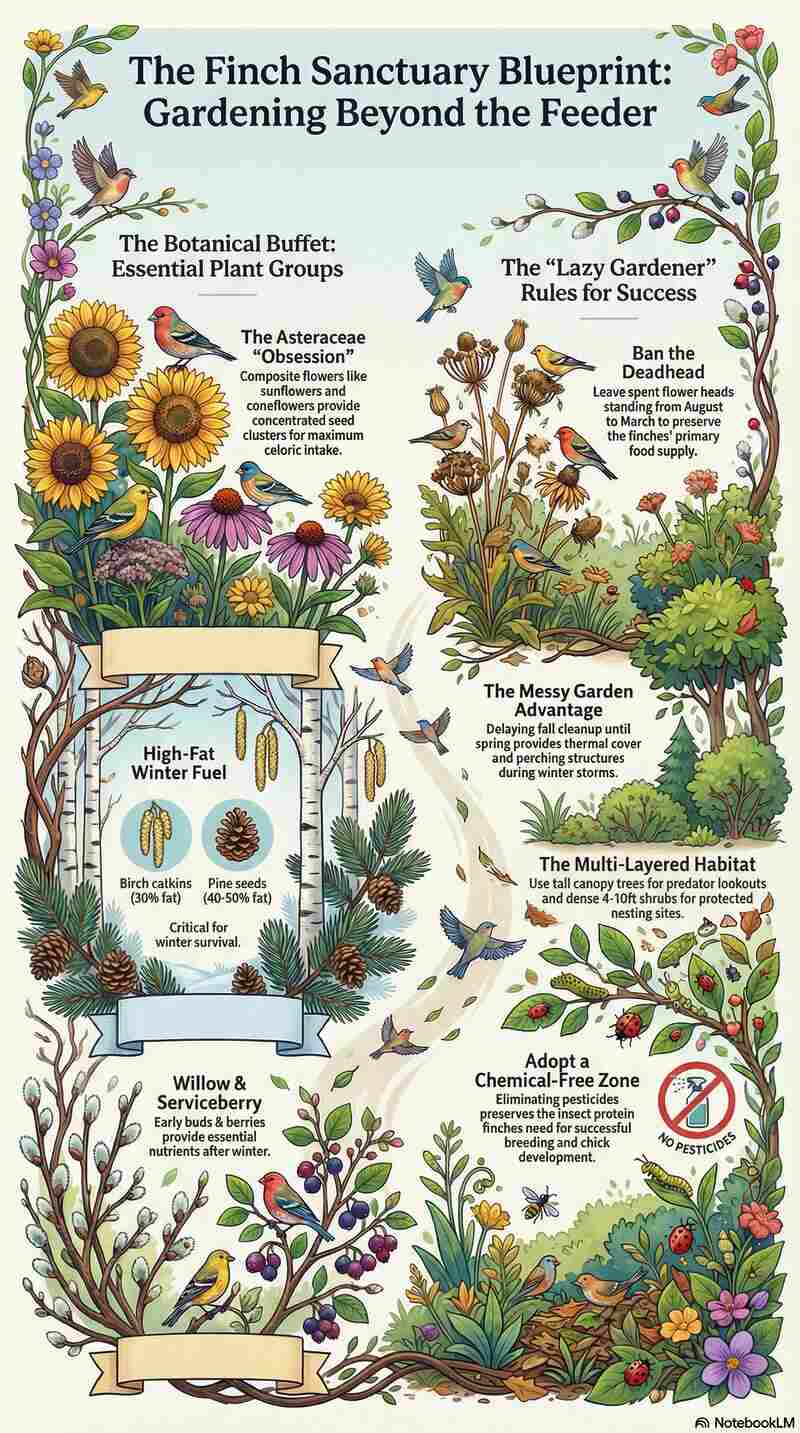

- Plant seed-heavy natives like coneflowers, sunflowers, and black-eyed Susans.

- Leave seed heads standing from late summer through early spring.

- Add birch, alder, willow, pine, or spruce for winter catkins and cones.

- Create layers: tall trees, dense shrubs, and wild ground patches.

- Stop deadheading and delay fall cleanup for maximum seed supply.

- Avoid pesticides and herbicides to protect insect protein sources.

- Group plants in drifts to create visible feeding stations.

- Plant native species suited to your region for long-term success.

- Think ecosystem, not feeder, for permanent returning finch populations.

Designing a Living Finch Ecosystem: The Botany of Attraction

Watch this visual breakdown to see how switching from feeders to backyard plants transforms your garden into a permanent, self-sustaining sanctuary for finches.

Show Transcript:

0:00 – Welcome to this explainer. Today, we’ll show you how to transform your backyard from a casual stop for finches into a permanent home they return to year after year. The key is learning to think like a botanist.

0:12 – This goes far beyond just putting out a bird feeder. We’re talking about building a thriving ecosystem where finches not only eat, but also nest, raise young, and survive winter.

0:28 – A feeder is a quick meal, convenient but temporary. Native plants create a self-sustaining environment with food, shelter, nesting materials, and security—supporting multiple generations of backyard birds.

0:47 – This mental shift is crucial: we’re moving from hosting birds for a quick snack to creating an entire habitat for finches to truly live in.

1:01 – How do we start? Plants are the foundation. Focus on species finches are naturally drawn to, especially the composite flower family—daisies, sunflowers, thistles. These co-evolved with finches and provide high-energy seeds essential for survival.

1:30 – Composite seed heads are nature’s perfect “dinner plates,” packed with hundreds of seeds. One flowerhead can produce over 2,000 seeds—enough to feed multiple birds for weeks.

1:49 – A true finch sanctuary isn’t about a single plant—it’s a continuous rolling buffet. As one plant finishes producing seeds, another begins. This ensures a reliable food source from early summer through late fall.

2:15 – Each plant serves a strategic role: purple coneflowers provide food above snow; thistles give high-fat seeds and nest-building fluff; ironweed offers protein for fall migration.

2:36 – A year-round sanctuary is essential. Summer flowers alone can’t sustain finches. Permanent infrastructure like trees and shrubs keeps finch colonies safe and fed during harsh winter months.

3:02 – Two critical winter strategies: catkins from birch and alder trees provide slow-release seeds, while conifer cones offer high-fat calories for extreme cold. Together, these can supply 70% of a finch’s winter diet.

3:40 – Beyond what to plant, how you arrange them matters. Use the layering method: canopy trees for predator watch, shrubs for nesting and cover, and ground layers for patches of wild food.

4:14 – The middle shrub layer acts as a nursery. Finches build nests safely, concealed from hawks and cats. Native trees, like oaks, provide insect protein vital for raising chicks—a key difference from ornamental non-native trees.

5:04 – Best management tip: do less. Stop deadheading flowers. Brown seed heads are a natural pantry for winter. Avoid cleaning up the garden in fall; standing stems provide food, perches, and shelter during storms.

5:58 – Rethink garden beauty: it’s not a sterile, manicured space, but a dynamic, buzzing ecosystem supporting finches year-round.

6:11 – Rewards build over time: first year, some visitors; by year three, first nests; by year five, a multigenerational finch colony—your permanent backyard legacy.

6:46 – Final thought: the choice is yours—provide a temporary feeder or create a self-sustaining, thriving habitat that supports generations of backyard birds. Build a world, not just a meal.

The Top 10 Seed-Bearing Flowers: The Finch Buffet

The Aster Family (Asteraceae): Biological Obsession Explained

According to Cornell Lab of Ornithology research, goldfinches eat seeds almost exclusively, with main types including seeds from composite plants in the Asteraceae family (sunflowers, thistle, asters), grasses, and trees such as alder, birch, western red cedar, and elm. According to research from the National Audubon Society, finches are attracted to the colorful flowers in the daisy (Asteraceae) family, which produce the small seeds favored by finches and also the downy fibers used to line nests.

The biological obsession runs deeper than simple seed preference. Asteraceae flowers produce composite seed heads where hundreds of individual seeds develop in concentrated clusters accessible to finch beaks and foraging techniques. The architecture matters. Each composite flower contains dozens to hundreds of tiny disc florets that mature into individual seeds, creating concentrated feeding opportunities where finches can harvest maximum calories with minimal energy expenditure.

The family includes over 32,000 species globally, making it one of the largest plant families. This diversity provides finches with seed sources available from early summer through late fall as different Asteraceae species bloom and set seed sequentially. American goldfinches, house finches, and purple finches all demonstrate strong preferences for Asteraceae seeds over other plant families when given choices in controlled feeding studies.

Purple Coneflowers (Echinacea): Structural Seed Production

Purple coneflowers produce elevated seed heads that remain accessible above snow throughout winter. The cone-shaped center (receptacle) contains 200-300 fertile disc florets that mature into individual seeds. Finches perch on the sturdy stems and systematically harvest seeds from the cone surface.

The no-deadhead rule proves critical for finch attraction. Gardeners trained to remove spent flowers for aesthetic purposes eliminate the very seed heads finches require. Leave coneflower seed heads standing from August through March. According to observations documented by birding researchers, goldfinches begin visiting coneflower seed heads in late July as seeds ripen, continuing visits through winter until seeds are depleted.

Echinacea purpurea (eastern purple coneflower) provides the most reliable seed production among cultivated varieties. Native to eastern North America, it thrives in full sun with moderate moisture. Plants reach 2-4 feet tall with large flower heads that produce abundant seeds. Space plants 18-24 inches apart in groups of 5+ for maximum finch attraction.

Black-Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia): Gateway Plant for House Finches

Whether in their classic bright yellow form or fiery bicolor varieties like this one, Rudbeckia hirta (Black-eyed Susan) serves as a vital introductory plant for house finches. These high-contrast flowers attract finches visually as their seeds ripen, training the birds to recognize the dark, conical centers as a reliable food source. House finches demonstrate a particular affinity for Rudbeckia seeds, often visiting these vibrant plants before exploring other Asteraceae options in the garden.

The species produces prolific seeds from midsummer through fall. Individual plants generate hundreds of seeds per flower head, with multiple flower heads per plant creating substantial seed crops. Plants self-seed readily, creating expanding patches that increase finch attraction year over year.

Black-eyed Susans tolerate a range of soil conditions from sandy to clay, requiring only full sun and moderate drainage. Plants reach 1-3 feet tall depending on variety. For maximum finch benefit, plant in drifts of 10+ plants rather than isolated specimens. The massed planting creates visual beacon and concentrated feeding station finches preferentially visit.

Native Sunflowers (Helianthus): Perennial vs. Annual Options

Giant garden sunflowers (Helianthus annuus cultivars) provide dramatic seed production but require annual replanting. A single large sunflower head can produce 1,000-2,000 seeds, creating temporary feast for finches and other seed-eaters. Plant in late spring for late summer seed production. Allow heads to dry on stems through fall and winter.

Native perennial sunflowers offer sustained finch value. Helianthus maximilliani (Maximilian sunflower) grows 4-10 feet tall with numerous smaller flower heads producing abundant seeds from August through October. Helianthus divaricatus (woodland sunflower) thrives in partial shade, extending sunflower habitat into areas unsuitable for sun-loving species.

Perennial sunflowers spread through rhizomes, creating expanding colonies that increase seed production annually. Established stands require no maintenance beyond leaving seed heads standing through winter. The combination of sustained seed production, minimal care requirements, and expansion tendencies makes native perennial sunflowers superior long-term finch plants compared to annual varieties.

Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium): Back of Border Late Bloomers

Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum and related species) grows 4-7 feet tall, providing vertical structure in native plantings. While its pink-purple flower clusters are a famed nectar source for butterflies from July through September, the plant’s true value for birds begins as the seeds ripen in October. These late-season seeds provide a critical energy boost just as many other native seed sources begin to decline.

The tall growth creates elevated feeding stations finches use as lookout perches while foraging. Birds scan for predators from Joe Pye tops before dropping to lower plants to feed. This dual function (feeding + predator detection) increases finch use of properties where Joe Pye grows compared to gardens lacking tall vertical elements.

Plant Joe Pye weed in moist to wet soils in full sun to part shade. The species tolerates seasonal flooding, making it ideal for low areas where other plants struggle. Space plants 2-3 feet apart in groups of 3-5 for optimal visual impact and finch attraction.

Ironweed (Vernonia): High-Protein Fall Migration Fuel

Ironweed (Vernonia species) produces seeds with higher protein content than many other Asteraceae, providing nutritional boost finches require during fall migration and pre-winter fattening. The deep purple flowers bloom August through September, with seeds ripening September through October during peak finch migration periods.

Plants reach 3-6 feet tall with multiple branching stems producing dozens of flower heads. Each head contains numerous small seeds finches extract efficiently. The vertical structure and late seed production makes ironweed particularly valuable for properties supporting migrating goldfinches and pine siskins during fall movement periods.

Zinnias: Quick-Start Annual for Immediate Finch Activity

Zinnias provide fastest path to finch attraction for new gardens. These tender annuals grow rapidly from seed planted in late spring, blooming within 6-8 weeks and producing seeds by midsummer. Finches begin visiting zinnia seed heads while flowers still show color, creating striking visual contrast of yellow birds on pink or red flowers.

The sturdy stems support finch weight during seed extraction. According to observations from backyard birders, goldfinches perch directly on zinnia stems while feeding, using their feet to stabilize position as they harvest seeds from flower heads. This acrobatic feeding behavior provides excellent viewing opportunities from indoor windows.

Plant zinnia seeds directly in garden beds after last frost, spacing 12 inches apart in full sun. Choose taller varieties (24-36 inches) over dwarf types for better finch access. Allow all seed heads to mature and dry on plants rather than deadheading for continued bloom.

Cosmos: Lightweight Flowers Encouraging Acrobatic Feeding

Cosmos bipinnatus creates airy, delicate flower structures that sway in wind, requiring finches to demonstrate their aerial feeding skills. The lightweight stems and flowers move under bird weight, forcing finches to use hovering and balancing techniques different from feeding on sturdier plants.

The seeds develop in late summer and fall. Individual cosmos plants produce hundreds of seeds across numerous flower heads. The species self-seeds prolifically, creating expanding stands that require minimal garden maintenance beyond initial planting.

Cosmos thrives in poor to average soils, making it ideal for challenging garden areas. Plants reach 3-6 feet tall in full sun. Sow seeds directly in spring for late summer bloom and fall seed production.

Globe Thistle (Echinops): Natural Nyjer Substitute

Globe thistle produces spherical flower heads covered in small seeds that mature in late summer. The architectural similarity to commercial nyjer (thistle) feeders attracts finches trained on feeder seed to investigate natural seed sources. The transition from feeder dependence to native plant foraging often begins when finches discover globe thistle in gardens.

Plants grow 2-4 feet tall with multiple flower heads per stem. The blue-purple flowers attract pollinators during bloom, followed by seed production that sustains finches. The spiny leaves deter browsing by deer and rabbits, making globe thistle reliable seed producer in areas where herbivores damage other plants.

Native Thistles (Cirsium): The Goldfinch Namesake

According to Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s NestWatch program, American goldfinches breed later than most North American birds, waiting to nest until June or July when milkweed, thistle, and other plants have produced their fibrous seeds, which goldfinches incorporate into their nests and also feed their young.

Native thistle species (Cirsium species) serve dual function for goldfinches. The seeds provide high-fat food source during late summer breeding period. The fluffy pappus (seed down) provides essential nesting material goldfinches require for nest construction. According to research on goldfinch nesting, females construct watertight nests so tightly woven with thistle down that the nests can hold water, sometimes drowning nestlings during heavy rains.

Field thistle (Cirsium discolor), tall thistle (Cirsium altissimum), and swamp thistle (Cirsium muticum) represent native species that provide finch benefits without the invasive properties of non-native thistles. Plant in full sun in areas where spreading through self-seeding is acceptable. The spiny foliage prevents most wildlife browsing.

Avoid invasive thistle species including Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) and bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare). These aggressive spreaders create management problems that outweigh their finch value.

Beyond Flowers: Trees and Shrubs for Year-Round Survival

The Seed-Producing Trio: Birch, Alder, and Willow Catkins

Birch trees (Betula species) produce catkins that persist through winter, gradually releasing small seeds that goldfinches, siskins, and redpolls consume throughout cold months. A mature birch produces millions of tiny seeds, creating concentrated winter food source when most other seeds are buried under snow or depleted.

The catkins hang from branch tips in clusters, remaining accessible above snow accumulation. Finches perch directly on catkins while feeding or hang beneath them, extracting seeds through repeated pecking. The high fat content (approximately 30% by weight) provides concentrated calories essential for winter thermoregulation.

River birch (Betula nigra), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), and yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis) all produce valuable catkin crops. Plant in full sun to partial shade with adequate moisture. Birches require minimal maintenance once established.

Alder species (Alnus species) function similarly to birches, producing persistent catkins rich with small seeds. Speckled alder (Alnus incana rugosa) thrives in wet soils unsuitable for birch, extending catkin habitat into swampy areas and stream edges.

Willow catkins (Salix species) emerge in early spring, providing critical food source during the period between winter seed depletion and summer seed production. Pussy willow (Salix discolor) and other native willows produce both catkin seeds and tender buds that finches consume during late winter and early spring.

Conifers for Winter Fuel: Spruce, Pine, and Hemlock

Conifer seeds provide high-fat emergency rations during severe winter weather. According to research from Maine Audubon, native coniferous species including pines, spruces, firs, cedars, junipers, hemlock, and tamarack provide seeds for finches in winter, with the mast crops of spruces being especially important to the irruptive movements of crossbills. These coniferous species also provide critical thermal cover during the cold of winter and needles for nest-building in summer.

Spruce cones (Picea species) open during dry winter days, releasing winged seeds finches extract from between cone scales. White spruce (Picea glauca) and red spruce (Picea rubens) produce reliable annual cone crops. Pine siskins demonstrate particular fondness for spruce seeds, often dominating feeding on these trees when cone crops are abundant.

Pine seeds (Pinus species) contain 40-50% fat by weight, providing extraordinary caloric density. Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) produces large cones with accessible seeds. Finches pry scales apart to reach seeds or glean seeds from snow surfaces after cones naturally release them.

Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) produces small cones with tiny seeds that goldfinches and siskins specialize in extracting. The dense evergreen foliage provides critical winter shelter where finches roost overnight and escape daytime cold.

Berries vs. Seeds: Elderberry and Serviceberry Supplementation

While finches focus primarily on seeds, house finches and purple finches supplement their diets with soft fruits during late summer and fall. Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) produces clusters of small purple-black berries that ripen in August and September, providing essential vitamins and moisture alongside their primary seed diet. Similarly, American Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) offers vibrant purple clusters that attract finches as a high-moisture snack during the peak of summer heat.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier species) produces sweet berries earlier in June and July. This early fruiting period provides a critical food source during the “gap” between spring seed depletion and summer seed production. House finches visit serviceberries and beautyberries opportunistically while primarily foraging for seeds elsewhere.

Berry consumption remains secondary to a seed-based diet. Plant elderberries, serviceberries, and beautyberries for their broader wildlife value, recognizing that finches will use them as a colorful supplement but will still depend on seed-producing plants for their core survival.

Advanced Habitat Design: The Layering Method

The Canopy Layer: High-Altitude Lookouts

Tall trees (30+ feet) provide essential predator detection perches. Finches feeding in low vegetation face constant threat from hawks, cats, and other predators. The ability to quickly escape to high canopy branches determines survival during predator encounters.

Native oaks, maples, and other deciduous trees create canopy structure. While these trees may not produce seeds finches prefer, their presence increases finch use of seed-producing understory plants by providing escape routes. Properties with good canopy cover support higher finch densities than open properties with abundant seed plants but no vertical escape options.

Position feeding areas (seed-producing flower beds) within 30-50 feet of mature trees. This distance allows finches to reach safety within 2-3 seconds of detecting threats while maintaining adequate sunlight for sun-loving seed plants.

The Shrub Layer: Escape Tunnels and Nesting Sites

Dense shrubs 4-10 feet tall create protected zones where finches nest and seek cover from aerial predators. According to research on goldfinch nesting preferences, these birds typically build nests 3-10 feet from ground in vertical forks of shrubs or small trees, with nest sites characterized by dense foliage providing overhead concealment.

Elderberry, buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), and native viburnums create ideal nesting structure. The dense branching provides multiple vertical forks suitable for cup-shaped finch nests. The foliage conceals nests from above (protecting from predatory birds) while leaving nests visible from below (allowing parent finches to monitor for ground predators).

Plant shrubs in irregular groups rather than formal hedgerows. Natural clustering creates varied heights and densities mimicking wild shrubland habitats finches evolved to use. Space individual shrubs 3-5 feet apart, allowing them to grow into interconnected thickets.

The Ground Layer: Wild Patches vs. Manicured Lawns

Dandelions, chickweed, and other lawn “weeds” produce seeds finches consume, particularly during early spring when tree and shrub seeds are depleted but perennial flowers have not yet bloomed. A 100-square-foot unmowed patch of mixed lawn weeds produces more finch food than an acre of manicured turf grass.

The strategy requires resisting the urge to mow, spray herbicides, or otherwise eliminate low-growing seed-producing plants. Designate specific areas (back corners, areas behind garages, strips along property edges) where vegetation grows wild. Allow dandelions, plantains, clovers, and grasses to bloom and set seed.

These wild patches also host the insects finches require during breeding season. Native bees, beetles, and other arthropods live in unmowed vegetation, providing the protein source parent finches need despite their primarily vegetarian diet.

The Lazy Gardener Rule: Seasonal Maintenance

Stopping the Deadhead: Standing Seed Heads

Conventional gardening advice emphasizes deadheading (removing spent flowers) to encourage continued bloom and maintain aesthetic appearance. This practice directly conflicts with finch attraction. Every deadheaded flower represents dozens to hundreds of seeds removed from finch food supply.

Cease deadheading entirely from midsummer onward. Allow coneflowers, black-eyed Susans, sunflowers, and all other seed-producing plants to complete their reproductive cycle. The brown seed heads many gardeners consider unsightly represent critical finch food stores.

The aesthetic shift requires accepting that finch-friendly gardens look different from conventional ornamental gardens. Dried seed heads, standing stems, and “messy” borders replace tidy, continuously flowering beds. The trade-off is clear: conventional garden aesthetics vs. permanent finch populations.

The Messy Garden Advantage: Fall Cleanup as Enemy

Fall garden cleanup traditions remove the very resources finches need for winter survival. Cutting back perennials, removing dried flower stalks, and cleaning up fallen seeds eliminates food sources finches depend on from November through March.

Delay all garden cleanup until late March or early April. Leave perennials standing through winter. Allow fallen seeds to remain on ground where finches can glean them. The standing vegetation provides both seeds and structure for perching while feeding.

Standing stems also create “roosting cover” where finches shelter during winter storms. Dense stands of dried vegetation block wind and create microhabitats several degrees warmer than surrounding open areas. The thermal benefit can determine finch survival during extreme cold snaps.

Staging Perches: Bird Parking Lots

Tall, sturdy seed stalks function as staging perches where finches land before dropping to lower feeding areas. Sunflower stalks, Joe Pye weed stems, and ironweed stalks create vertical perches 4-8 feet tall that finches use for predator scanning and social interaction.

These staging areas become finch gathering spots where birds congregate before dispersing to feed. The vertical structure visible from distance serves as beacon attracting passing finches to investigate feeding opportunities below.

Intentionally leave the tallest, sturdiest stalks standing even when cutting back shorter vegetation. Create vertical “landmarks” spaced throughout garden that serve as finch navigation and gathering points.

The Protein Factor: Attracting Beneficial Insects

The Breeding Season Diet: Caterpillars and Aphids

Despite their reputation as strict vegetarians, American goldfinches require insect protein during breeding season. According to Cornell Lab research, goldfinches are among the strictest vegetarians in the bird world, selecting an entirely vegetable diet and only inadvertently swallowing an occasional insect. This dietary specialization means finches consume small insects and spiders incidentally while eating seeds, with insect consumption increasing during breeding when protein needs peak for egg production and chick development.

Native plants host native insects in ways non-native plants cannot. An oak tree supports over 500 caterpillar species while most non-native trees support fewer than 10. Native coneflowers, asters, and sunflowers similarly host abundant aphids, beetles, and other insects finches consume.

The protein comes primarily from insects finches consume inadvertently while eating seeds or deliberately when protein needs increase. Plant diversity correlates directly with insect diversity, which in turn supports higher finch breeding success. Properties with 30+ native plant species support significantly more breeding finches than monoculture landscapes regardless of total seed production.

Eliminating “Cides”: Pesticides Destroy Food Chains

Pesticides and herbicides eliminate the insects finches require while simultaneously contaminating seeds finches consume. Systemic insecticides (neonicotinoids) enter all plant tissues including seeds, poisoning finches that eat treated plants.

Herbicides eliminate “weed” species that produce critical finch foods. Dandelions, ragweed, and other herbicide targets rank among the most important finch food plants. Selective herbicide application that preserves lawn appearance while eliminating finch food sources creates ecological dead zones attractive to neither finches nor other wildlife.

Adopt entirely chemical-free approach to yard management. Accept presence of insects as essential ecosystem components rather than problems requiring elimination. The trade-off is simple: perfect lawns and pest-free ornamentals vs. living ecosystems supporting finches and other wildlife.

Regional Planting Guide: Native Recommendations

Northeast (Zones 4-6)

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), and New England aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) provide reliable seed production throughout growing season. Paper birch (Betula papyrifera) and eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) offer winter seeds and shelter.

Joe Pye weed thrives in moist areas while coneflowers handle drier sites. This combination creates seed availability across varied moisture regimes within single property.

Southeast (Zones 7-9)

Black-eyed Susan, purple coneflower, and lanceleaf coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata) provide primary seed sources. River birch (Betula nigra) tolerates heat and humidity while producing abundant catkins. Southern wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera) offers winter shelter and secondary food source.

The longer growing season allows for extended blooming periods and multiple seed crop production from reblooming perennials.

Midwest (Zones 4-6)

Prairie natives dominate optimal finch plantings. Purple coneflower, black-eyed Susan, gray-headed coneflower (Ratibida pinnata), and prairie dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum) create diverse seed sources. Willow and birch catkins provide winter supplements.

The region’s natural prairie heritage means native seed plants thrive with minimal maintenance once established. Properties with even small prairie plantings attract winter finch flocks that would otherwise bypass the area.

West (Zones 5-8)

Native sunflowers (Helianthus species), blanketflower (Gaillardia species), and native thistles provide seed sources adapted to arid conditions. Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) offer winter seeds in mountain and foothill areas.

Drought tolerance becomes critical consideration. Select species proven for local conditions rather than attempting to grow moisture-loving plants in dry climates.

Finch Habitat Architecture: The Visual Master Plan

Before you start planting, use this master plan to visualize how each layer of your landscape from the high canopy to the wild ground patches works together to sustain a multi-generational finch colony.

Conclusion: Building a Living Ecosystem

The transformation from feeder-dependent finch visits to self-sustaining finch colonies requires ecosystem thinking rather than bird-feeding mentality. Individual plants matter less than plant communities. Seed production from single species matters less than sequential blooming creating year-round food availability. Garden aesthetics matter less than ecological function.

The social network effect amplifies as finch-friendly plantings mature. First-year gardens attract occasional visits. Third-year gardens host breeding pairs. Fifth-year gardens support multi-generational colonies where young birds hatched on-site return as adults to breed in the same habitat that sustained their parents.

The permanence differs fundamentally from feeder relationships. Feeders create dependency that disappears when you stop filling them. Native plantings create self-renewing ecosystems that persist whether you actively maintain them or not. The plants reseed themselves. The insects colonize on their own. The finches return because habitat exists, not because you provided it this particular week.

Success requires accepting that peak finch activity occurs when gardens look least conventionally attractive. Late summer and fall seed production happens on dried brown flower heads. Winter feeding occurs on weathered stalks and persistent catkins. Spring nesting uses down from previous year’s seed heads. The entire annual cycle depends on restraining the urge to cut, clean, and tidy.

For readers who want to supplement plant-based habitat with traditional feeding, explore guides on setting up finch feeders, understanding winter finch diets, and identifying different finch species. Understanding broader native plant benefits for all birds and general bird-friendly garden design principles provides context for integrated approaches combining plantings with supplemental feeding strategies. The ideal habitat merges both approaches, creating resilient systems where finches thrive regardless of whether feeders remain filled.