Ever wondered what fuels a bird’s day, from hatchling to adult? If you’ve ever wondered what birds eat in the wild, the answer depends on the season and the species. Most wild birds forage for insects, caterpillars, berries, fruits, seeds, and nuts, not just seeds in feeders. This guide focuses on what birds eat naturally in the wild, not how to stock or use bird feeders.

Many modern yards, however, are filled with ornamental, non-native plants that provide little food for birds. By planting native trees, shrubs, and perennials, you can create a self-sustaining “wild food web” that supplies birds with the seasonal foods they need to survive, raise young, and migrate successfully. Start small, and watch your yard transform into a thriving haven for local wildlife. 🙂

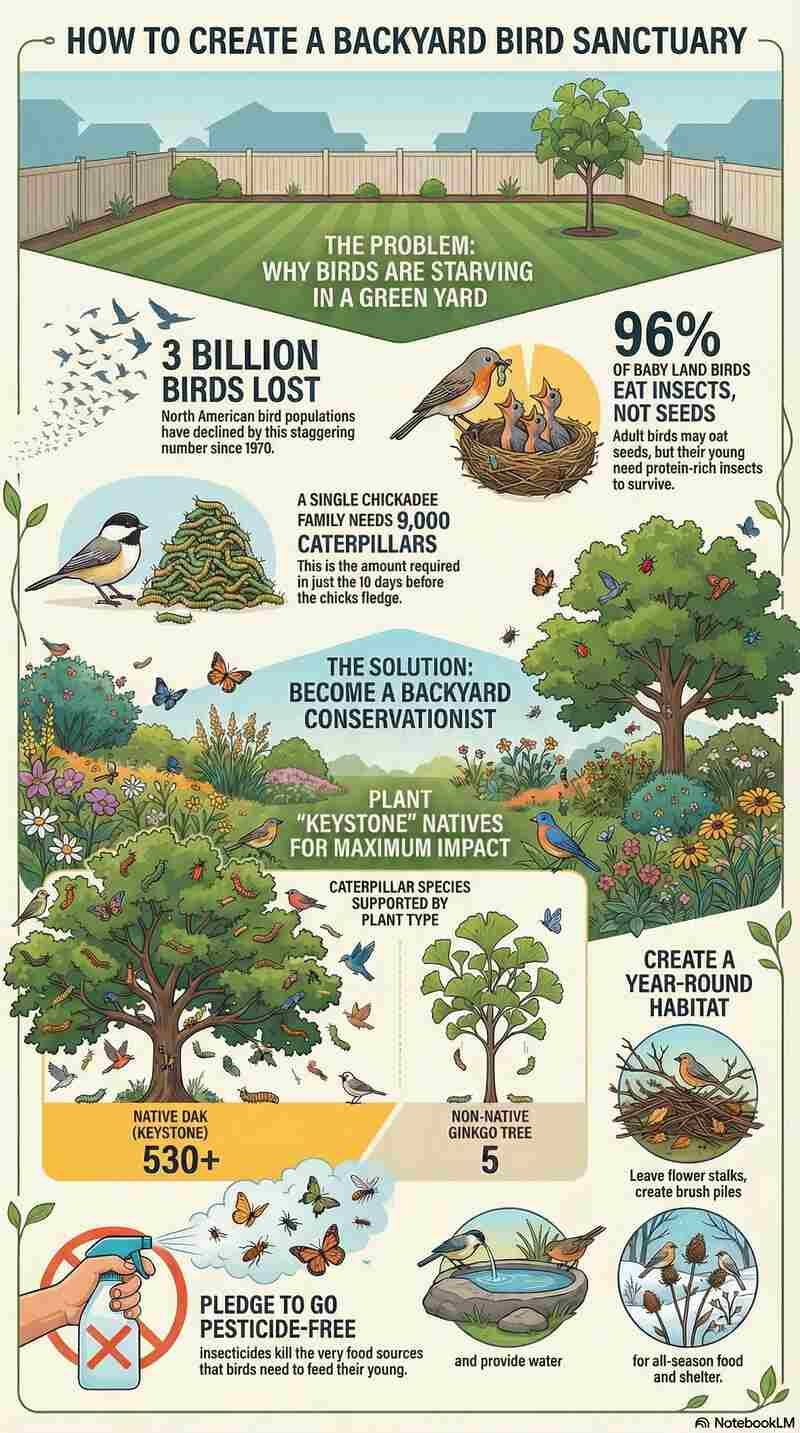

- North American bird populations have plummeted by nearly 3 billion since 1970.

- Many yards with non-native plants offer little food or shelter for birds.

- Supplemental feeders with seeds or suet can help in winter.

- Most wild birds forage naturally for insects, berries, and seeds.

- Adult birds eat seeds, berries, and fruits; babies require protein-rich insects.

- Caterpillars are the most crucial food for nestlings, providing protein and carotenoids.

- Native host plants like oaks, cherries, willows, and birches support caterpillars.

- Seasonal native foods fuel birds year-round: buds, sap, fruits, seeds, nuts, and insects.

- Standing perennials, leaf litter, and brush piles provide winter food and shelter.

- Providing water and avoiding pesticides completes a healthy bird habitat.

Watch What Birds Eat in the Wild (5-Minute Guide)

Curious what birds eat in the wild? In just five minutes, we’ll show you the key foods, seeds, berries, insects, and caterpillars, that keep birds thriving all year long.

Show Transcript

0:00

Hey, and welcome to the explainer.

Today we’re going to talk about an incredible conservation story.

0:04

And here’s the surprising part.

It’s not happening in some far-off rainforest or the middle of the ocean.

0:08

Nope.

It’s happening right in our own backyards.

0:14

Alright, let’s start with a number.

And honestly, it’s a hard one to wrap your head around.

0:19

Since 1970, North America has lost almost 3 billion birds.

0:23

Think about that for a second.

That’s a staggering decline.

0:27

It’s a massive loss of life, and a loss of sound too.

The sound from our skies and neighborhoods.

0:32

It’s a crisis.

And yeah, it can feel overwhelming.

0:39

But here’s the thing.

What if a huge part of the solution isn’t some massive, complicated policy?

0:43

What if it’s something much closer to home?

0:46

What if the power to start turning this around is literally right outside your window?

0:54

So why is this happening?

0:57

Let’s dig into why so many of our yards have gone silent.

Why that familiar bird chorus is starting to fade.

1:05

This flips the idea of a “perfect lawn” on its head.

1:07

A lot of our yards are filled with beautiful plants from Europe or Asia.

1:11

They look great.

But to local wildlife, they’re basically dead zones.

1:16

They’re green.

They look alive.

1:18

But they offer almost zero food or shelter.

1:23

Why?

Because local insects haven’t evolved to eat them.

1:30

So the next logical step for many people is this:

“I’ll put out a bird feeder.”

1:36

And look, that does help.

But only up to a point.

1:41

It’s based on a big misunderstanding of what birds really need to thrive.

1:47

We see adult birds at feeders, and yes, they love seeds.

1:52

But their babies?

That’s a completely different story.

1:56

Here’s the key fact.

1:59

About 96% of land birds feed their young only insects.

2:01

For nestlings, seeds aren’t an option.

2:04

Baby birds can’t digest hard seeds.

2:06

They need soft, protein-rich food that fuels rapid growth.

2:11

Without a steady supply of insects, the next generation simply doesn’t survive.

2:25

So if insects are the key, one group stands far above the rest.

2:29

This is the real superfood for birds.

2:32

Caterpillars.

2:38

They’re soft.

They’re packed with protein.

And they’re loaded with essential fats.

2:44

They fuel the entire bird world.

2:51

And the numbers are mind-blowing.

2:53

A single pair of chickadees needs over 9,000 caterpillars to raise one brood.

3:01

Nine.

Thousand.

3:05

Without caterpillars, birds can’t raise families.

Period.

3:14

And it’s not just about protein.

3:16

Caterpillars contain carotenoids.

3:20

Birds can’t make these pigments themselves.

They have to get them from food.

3:24

These pigments create those bright reds and yellows in feathers.

3:28

So when you see a vibrant bird, it’s signaling health and access to good food.

3:36

So now the big question.

3:38

How do we get more caterpillars?

3:43

The answer comes down to one basic idea:

co-evolution.

3:46

Over thousands of years, insects evolved to digest specific native plants.

3:52

A caterpillar adapted to oak leaves can’t suddenly eat a ginkgo from Asia.

4:14

To that caterpillar, non-native plants are basically inedible.

4:19

And the difference is dramatic.

4:21

A native oak can support over 530 species of caterpillars.

4:26

A non-native ginkgo?

Maybe five.

4:36

That’s why plants like oaks are called keystone species.

4:41

And it’s not just oaks.

4:43

Native cherries, willows, and birches are powerhouses too.

4:50

Planting just one keystone tree or shrub is one of the most effective actions you can take.

5:00

But a full habitat means thinking year-round.

5:04

Take berries, for example.

5:14

Native berries like dogwood are rich in fats that fuel migration.

5:25

Invasive honeysuckle berries are mostly sugar.

5:28

They’re bird junk food.

5:37

A strong habitat also needs:

5:41

• Year-round water

• Shelter like brush piles or safe dead trees

• Winter cover

5:51

Leaving fallen leaves and old flower stalks protects overwintering insects.

5:57

Those insects become winter food for birds like chickadees.

6:04

And finally, the most important rule of all.

6:06

Avoid pesticides.

6:08

They kill the exact insects birds depend on.

6:14

A garden with bugs isn’t a problem.

It’s proof the system is working.

6:23

So it all comes down to four simple steps:

6:28

- Plant one keystone native.

- Add a water source.

- Leave the leaves in fall.

- Go pesticide-free.

6:43

Every native plant you add can become the foundation of a local food web.

6:49

It’s a small act, but a powerful one.

6:54

And it starts with you.

6:55

So the only question left is this:

6:58

What’s your first one going to be?

Why Seeds Alone Are Not Enough in the Wild

While adult birds certainly benefit from seed-filled feeders, especially in winter, seeds are not the food that raises the next generation. The vast majority of baby birds cannot digest seeds. To survive the critical period from hatching to fledging, they require an immense amount of protein-rich, soft-bodied insects. For tips on supplementing adult birds’ diets during harsh weather, see our guide on feeding birds in winter.

Research shows that an incredible 96% of North America’s land-based birds feed insects to their young, according to PBS Nature. Of all the insects available, one group stands out as the single most important food source: caterpillars. Without a robust local population of caterpillars, native bird populations simply cannot reproduce successfully, no matter how much seed we provide.

While feeders can supplement adult birds’ diets in winter, they cannot replace the natural insects that young birds need to grow and thrive.

Why Natural Food Sources Matter for Wild Birds

According to research North American bird populations have declined by nearly 3 billion since 1970, and one of the biggest reasons is the loss of natural food. As native plants disappear from neighborhoods, so do the insects, caterpillars, berries, and seeds birds depend on to survive and reproduce.

While bird feeders can help during harsh weather, they cannot replace a functioning food web. Wild birds need a steady supply of natural foods throughout the year, especially protein-rich insects for raising young and high-fat fruits for migration and winter survival. See the natural diet of birds in the wild to learn how planting native species can provide the food birds truly need.

Keystone Foods: The Protein Crisis

Caterpillars: Baby Bird Fuel

Caterpillars are the ultimate “baby bird food.” They are soft, easy to digest, and packed with the high levels of protein and fat that nestlings need for rapid growth. The sheer quantity required is astounding: studies have shown that a single clutch of Carolina Chickadee chicks can consume over 9,000 caterpillars in the 16 days between hatching and fledging. Without access to this specific food source in such abundance, the nest will fail.

Beyond basic nutrition, some caterpillars are also an unusually good source of essential carotenoids. These are natural pigments that birds cannot produce themselves. When consumed, carotenoids are what create the brilliant red, orange, and yellow plumage in many species. A brightly colored bird is not just beautiful; it is signaling its excellent health and foraging success to potential mates, a crucial factor in successful breeding.

This highlights why supplemental feeding with store-bought insects is an incomplete solution. While offering mealworms can help, it creates a nutritional monoculture. As one source notes, “Mealworms provide protein but not much else.” They lack the rich variety of nutrients, enzymes, and especially the critical carotenoids found in a diverse diet of wild caterpillars.

The Native Host Plant Connection

The reason many modern yards lack caterpillars lies in the concept of co-evolution. Over millennia, native insects have adapted to feed on the specific foliage of native plants, developing ways to digest the unique chemical compounds each plant produces for defense. Consequently, most native insects cannot recognize or digest the leaves of non-native plants from Asia or Europe.

A yard filled with ornamental, non-native plants may be green, but to local insects, it is an inedible desert. Studies show that yards with less than 70% native plant biomass function as population sinks, where Carolina chickadees either fail to breed or produce fewer young due to insufficient caterpillar availability.

This is where keystone species become so important. Keystone plants are native species that support an exceptionally high number of butterfly and moth species (and therefore, their caterpillars). The difference is stark. In the mid-Atlantic region, for example, a native oak tree can support over 530 species of caterpillars. By contrast, the non-native Ginkgo tree, a common landscape ornamental, supports only 5.

Other powerhouse keystone genera that fuel the food web include native cherries, willows, and birches. Planting native plants for birds, especially keystone species, is the most effective way to provide the insect protein needed to support local bird populations. These plants help supply the crucial food that 96% of songbirds need to raise their young.

Planting native keystone species is the single most effective action any gardener can take to provide the insect protein necessary to support local bird populations and help reverse their decline.

Spring: Fueling Migration & Nesting

Spring is a time of immense energy expenditure for birds. Migrants are arriving from long, arduous journeys, resident birds are establishing territories and building nests, and all are preparing to raise young. They require immediate and varied sources of fuel, which a healthy native landscape provides long before the first summer fruits appear.

While feeders stocked with seeds or suet can offer short-term help during late cold snaps, spring nutrition still depends mainly on naturally available insects, buds, sap, and early native blooms.

Early Buds, Sap, and Nectar

Before leaves emerge, some of the earliest food sources are found directly on woody plants. Finches and grosbeaks feast on the nutrient-rich buds of trees such as elm and river birch, giving them an essential energy boost. At the same time, Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers begin drilling their characteristic wells into maples and birches.

These sap wells become vital feeding stations not just for the sapsuckers, but for other species like hummingbirds, kinglets, and nuthatches that will visit to drink the sweet, energy-rich sap. As the first migrant hummingbirds arrive, they depend on early-blooming native nectar sources.

Key plants include the brilliant red flowers of Coral Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) and the delicate blooms of Wild Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) and Virginia Bluebells (Mertensia virginica).

Persistent Winter Berries and First Insects

Some native berries are not palatable in the fall and are often ignored by birds. However, after months of freezing and thawing, their chemical composition changes, making them a soft, accessible, and crucial food source in the lean days of early spring. Plants that offer these persistent, high-fat fruits include Winterberry (Ilex verticillata), Sumac (Rhus sp.), and Hawthorn (Crataegus sp.).

As the ground thaws, ground-feeding birds like American Robins and other thrushes begin probing the soil and leaf litter for their first meals of earthworms, snails, and other invertebrates emerging from dormancy.

Summer: A Buffet of Fruits & Insects

Summer is a season of abundance in a native garden. The insect population is at its peak, providing the protein needed to raise young, while a succession of soft, sugar-rich fruits offers energy for active adult birds.

A Bounty of Soft Fruits

Several native shrubs are specialists in producing soft, easily digestible fruits in early summer, a time when few other fruit sources are available. These plants become magnets for a wide variety of birds. Serviceberry (Amelanchier sp.) is one of the first to ripen, attracting Cedar Waxwings, thrushes, vireos, robins, orioles, and bluebirds.

Soon after, Blueberry (Vaccinium sp.) and Elderberry (Sambucus sp.) offer their own bounty, ensuring that fruit-eating birds have a continuous food supply to supplement their insect-heavy diet.

Sustaining the Insect Larder

Throughout the summer, parent birds work tirelessly to feed their hungry nestlings. A landscape rich in native host plants ensures a continuous supply of caterpillars and other insects. Powerhouse shrubs like Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) host the striking Spicebush Swallowtail caterpillar.

Stands of native Milkweed (Asclepias sp.) are famous as the essential host plant for Monarch butterfly caterpillars, but they also attract a host of other insects that are readily eaten by birds, making them a cornerstone of a summer bird garden.

Research from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology emphasizes that native plants like oaks can support over 500 species of caterpillars, providing the crucial food that 96% of songbirds need to raise their young.

Foraging on the Ground Floor

The garden floor is a critical foraging zone. A healthy layer of leaf litter and moist soil provides a habitat for snails, slugs, earthworms, and countless other invertebrates. This “ground floor” is the primary feeding territory for birds like American Robins, thrushes, and wrens, which can be seen flipping leaves and probing the soil in search of these protein-rich meals.

Autumn: Stocking Up for the Journey Ahead

Autumn is a critical preparation period. Migratory birds must build up significant fat reserves to fuel their long flights, while resident birds need to store energy to survive the coming winter. The foods provided by native plants in the fall are uniquely suited to meet these high-energy demands.

The Critical Role of High-Fat Fruits

Unlike the sugar-rich berries of summer, native fruits that ripen in the fall are exceptionally high in fat. This dense caloric fuel is precisely what migrating birds need. For example, the berries of the Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) can be nearly 50% fat.

Contrast this with summer fruits like wild raspberries, which are typically less than 1% fat. This is why berries from many non-native invasive shrubs are considered “junk food.”

These berries, from plants like invasive honeysuckle, are high in sugar but low in the essential, long-burning lipids required for the arduous journey of migration or for surviving a cold winter night. Learn which birds to attract in fall for maximum backyard activity.

They are a poor substitute for native, high-fat options like Dogwood (Cornus sp.) and Viburnum (Viburnum sp.).

Nuts, Acorns, and Mast Crops

As fall progresses, trees like Oaks (Quercus sp.) and Hickories (Carya sp.) begin to drop their mast crops. These acorns and nuts are a vital food source for a different suite of birds. Blue Jays are famous for harvesting and caching acorns, while woodpeckers, titmice, and nuthatches work diligently to extract the rich food from these hard shells.

The Enduring Gift of Standing Perennials

One of the most beneficial actions a gardener can take is to leave perennial flower stalks and native grasses standing through the fall and winter. The seed heads of plants like Coneflowers (Echinacea/Rudbeckia), Sunflowers (Helianthus sp.), Asters (Symphyotrichum sp.), and Goldenrod (Solidago sp.) provide a crucial, easily accessible food source.

These seeds are perfect for seed-eating birds like American Goldfinches, sparrows, Dark-eyed Juncos, and chickadees, which will cling to the stalks to extract the seeds all winter long, even during harsh weather.

Winter: How Wild Birds Find Food

Winter is the season that tests a bird’s limits. Natural food sources become scarce and are often hidden by snow and ice, while cold temperatures demand a higher caloric intake just to stay warm. A well-designed native garden continues to provide essential food and resources even in the harshest conditions.

During prolonged cold spells, bird feeders filled with high-energy foods like black oil sunflower seeds or suet can be a helpful supplement, but many species still rely heavily on naturally occurring berries, seeds, buds, and hidden insects to survive the winter.

Persistent Berries, Seeds, and Buds

As mentioned, the seed heads of last year’s perennials and grasses are a lifeline for finches and sparrows. Additionally, some fruits that were passed over in the fall become critical survival food.

The bright red berries of Winterberry persist all season, often eaten by returning robins in late winter. The fuzzy red fruit clusters of Staghorn Sumac remain on the plant, providing emergency food for dozens of species.

The dark blue berries of Virginia Creeper and the berry-like cones of Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) are also important late-season resources.

For some birds, even the dormant buds of trees, like those on a Pussywillow (Salix discolor), are a source of sustenance for species like the ruffed grouse.

The Hidden World of Arthropods

Even in the depths of winter, birds are experts at finding hidden food. A tidy garden offers little, but a garden with standing perennial stems, loose bark on trees, and a layer of leaf litter is a winter pantry. Chickadees, nuthatches, and woodpeckers meticulously glean dormant insects, spiders, and their eggs from these locations.

They will pry open the hollow stems of old perennials to extract the insects sheltering inside. The Brown Creeper is a specialist at this, probing bark crevices for spiders even in single-digit temperatures. This hidden world of arthropods provides the essential fats and proteins that seeds alone cannot.

Water: The Forgotten Necessity

Just as critical as food in the winter is a reliable source of open water. Birds need to drink and bathe year-round, and bathing is especially important in winter to keep feathers in prime condition for insulation.

Finding unfrozen water can be a huge energy drain for birds. You can provide a vital service by maintaining a bird bath and using a simple, safe immersion heater to keep the water from freezing on the coldest days.

Beyond Just Planting: Creating a Complete Habitat

Providing a diverse menu is only half the equation; a truly living sanctuary also offers the physical structure birds need for shelter, nesting, and safety year-round. A truly bird-friendly landscape is more than just a collection of plants; it’s a complete habitat architecture that provides for all of a bird’s needs.

The Value of Dead Wood and Brush Piles

When it is safe to do so, leave dead trees (known as snags) standing. Snags are insect magnets, providing a constant source of food for woodpeckers and other gleaners. The cavities that woodpeckers excavate later become essential nesting sites for secondary cavity-nesters like bluebirds, chickadees, and titmice.

For smaller-scale habitat, create brush piles from pruned branches and plant clippings. These piles offer birds critical shelter from harsh weather and a safe haven from predators like hawks and outdoor cats.

Embracing Native Grasses and Vines

Don’t overlook the structural importance of native bunch grasses like Little Bluestem. They provide seeds, offer nesting materials, and their clump-forming habit creates sheltered pockets on the ground for foraging birds.

Likewise, native vines can be incredibly valuable. The fruits of Virginia Creeper and wild Grapes (Vitis sp.) are eaten by dozens of bird species, and their dense tangles provide excellent nesting and cover.

The Pledge to Avoid Pesticides

Finally, the most important pledge a wildlife gardener can make is to avoid all pesticides. Insecticides kill the caterpillars and other insects that form the base of the avian food web, effectively poisoning the very food your birds need to feed their young.

Herbicides kill the “weeds” that may be valuable native host or seed plants. A living, thriving garden will have insects—that is the sign of a healthy, functioning ecosystem.

Visual Guide: What Birds Love to Eat

This visual guide breaks down the foods birds depend on most, season by season.

Conclusion: Your Yard, A Living Sanctuary

By shifting our perspective, we can transform our yards from sterile, ornamental landscapes into vibrant, self-sustaining ecosystems. This is a powerful act of conservation that starts at home. By planting a diversity of native trees, shrubs, and perennials, you can provide a complete, year-round, natural diet for local and migratory birds.

You will not only be rewarded with a greater diversity of birdlife but will also be making a direct, tangible contribution to reversing bird population declines. You can begin this rewarding journey with just one native plant. Even a small bird feeder can supplement your yard’s natural food web, but the key to thriving wild populations is a diverse, native landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

What do birds eat in the wild instead of bird feeders?

Wild birds eat insects, caterpillars, seeds, berries, fruits, nuts, and tree buds or sap. Babies rely on protein-rich insects, while adults get energy from seeds and high-fat berries.

Which natural food provides the highest fat for migrating birds?

Berries from native shrubs that ripen in the fall are exceptionally high in fat, which provides critical fuel for migration. For example, native Spicebush berries can be up to 50% fat, making them an incredibly efficient energy source.

Do wild birds eat tree sap or buds?

Yes. In early spring, before other foods are available, birds like finches and grosbeaks will eat the nutrient-rich buds of trees. Sapsuckers are famous for drilling wells to drink sap, and other species, including hummingbirds and nuthatches, will take advantage of these wells to drink the sap as well.

Why should I leave old flower stalks and grasses standing in winter?

There are two primary reasons. First, the seed heads on plants like coneflowers and asters provide a vital food source for seed-eating birds such as goldfinches, sparrows, and juncos. Second, the hollow stems and surrounding leaf litter provide essential shelter for overwintering insects, which birds like chickadees and woodpeckers will forage for all winter long.

Which native trees support the most caterpillar food?

Native oak trees are the top keystone species, supporting over 530 different species of caterpillars, which are essential food for baby birds. Other excellent choices for hosting a high diversity of insects include native cherry, willow, and birch trees.

Are berries from non-native shrubs bad for birds?

Berries from many non-native, invasive shrubs are significantly less nutritious. They tend to be high in sugar and low in the essential fats that migrating and wintering birds need to survive. They are often compared to “junk food” for birds, offering quick energy but lacking the sustained fuel required for long journeys or cold nights.

How do birds find insects in winter?

Birds are expert foragers. Even in deep winter, they find dormant insects, spiders, and eggs by meticulously gleaning them from tree bark, digging through leaf litter, and breaking open the hollow stems of dead perennials where insects have taken shelter.

What foods help birds show brighter plumage?

Some caterpillars are rich in natural pigments called carotenoids. Birds cannot produce carotenoids themselves and must get them from their diet. These pigments are essential for creating bright red, orange, and yellow feathers, which often signal good health and are used to attract mates.

Can I feed wild birds in my backyard?

Yes! While wild birds mostly forage naturally, offering supplemental seeds, suet, or mealworms in winter can help, but it should never replace a diverse, native habitat.

What do birds feed their babies besides birdseed?

Almost all baby land birds (96%) are fed insects, not seeds. Caterpillars are the most important food source because they are soft, easy for nestlings to digest, and extremely high in the protein and fats necessary for rapid growth.