Traditional bird feeding often fails in July and August. You refill feeders, clean baths, and still wonder why your yard feels quiet. The problem isn’t your effort—summer birds need different resources. Fledglings require thousands of caterpillars daily, and adults seek high-fat fruits for molting and migration prep. Knowing what to plant for birds in summer ensures your yard provides the seasonal foods that truly meet their needs.

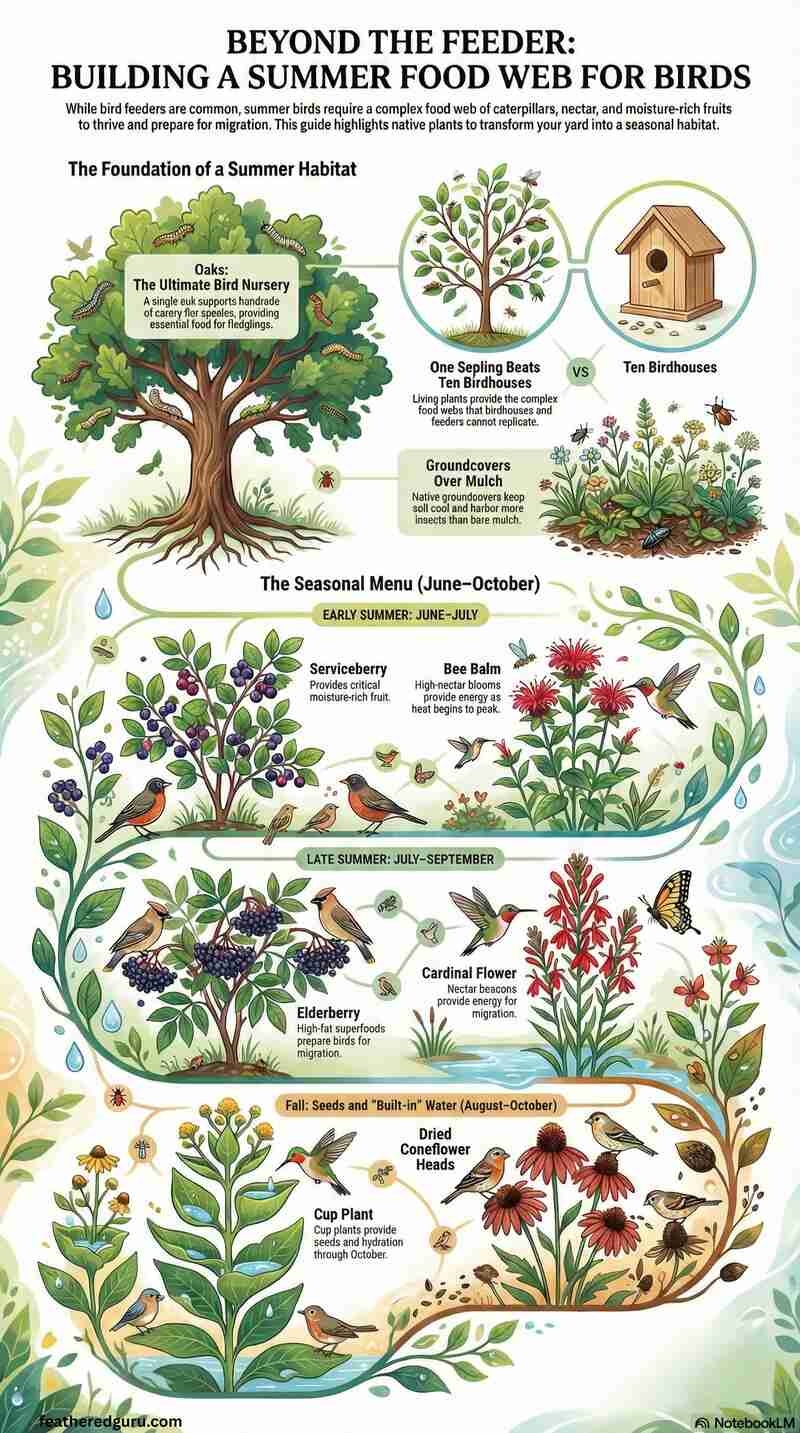

This guide moves beyond static feeders to create a high-performance summer habitat. You’ll learn which plants give early-summer moisture through serviceberries, which late-season natives fatten migrating birds, and why caterpillars on a single oak sapling can outvalue any birdhouse. You’ll also master timing strategies to avoid resource gaps during the months when backyard habitats matter most to nesting and migrating birds 🙂.

Quick TL;DR: Top Summer Bird Planting Tips

- Natural Food: Birds need plants more than feeders from July–Sept.

- Caterpillars: Fledglings require thousands; native plants are essential.

- Migration Fuel: Serviceberry, elderberry, and viburnum fuel long flights.

- Better Nutrition: Native berries beat invasive fruits in fat and energy.

- Hummer Support: Bee balm and agastache provide nectar in high heat.

- No Food Gaps: Overlap bloom times to provide a steady food supply.

- Don’t Deadhead: Leave seed heads to feed goldfinches through fall.

- Water & Food: Cup plant provides seeds and a natural water source.

- Beat the Heat: Plant in morning/evening to reduce seedling stress.

- Keystone Power: One oak sapling supports more birds than a birdhouse.

Video Guide: What to Plant for Birds in Summer

This short video explainer covers the core concepts of creating your summer bird haven and is a great visual summary of the key points discussed in the article:

Show Transcript:

0:00 – All right, let’s solve a mystery that frustrates so many bird watchers: why does your backyard go silent in the middle of summer? More importantly, how can you turn it back into a thriving, bird-friendly habitat that’s alive with songbirds and activity?

0:14 – You know exactly what I’m talking about. Spring is full of color and song, but by July or August, your yard can feel eerily quiet, like the birds just vanished. Where did they go, and how do we bring them back as permanent residents rather than occasional visitors?

0:45 – That quiet is real. Birds haven’t disappeared—they’ve just moved temporarily because your yard isn’t meeting their summer needs. Understanding why they leave is key to creating a bird-friendly backyard ecosystem.

1:00 – The solution requires a big shift in thinking. You need to go beyond feeders and start building a backyard food web. Summer isn’t downtime for birds—it’s their busiest, most critical season.

1:13 – Birds are busy raising chicks that need thousands of caterpillars to survive, molting their feathers, and preparing for migration. A feeder alone can’t provide the protein they need. Think of a feeder as a snack bar; a backyard food web is a full grocery store that sustains families from egg to fledgling.

1:53 – To create this summer bird buffet, timing is everything. You need food available all season, matching what birds require each month. This creates a continuous buffet that supports nesting birds, fledglings, and adult songbirds alike.

2:16 – Let’s start with the superstar: a single native oak tree. One oak can support over 500 species of caterpillars, providing abundant high-protein food for baby birds. One oak sapling can be more valuable than ten birdhouses because it creates the food needed to raise a family.

2:52 – Variety is essential. Early summer plants like serviceberry provide moisture-rich fruits for bluebirds and robins. Mid-summer blooms such as bee balm and cardinal flower attract hummingbirds. Late summer and fall, elderberry and viburnum offer fatty berries that fuel migrating birds.

3:14 – Leave seed heads on coneflowers and ironweed to feed finches through winter. Also, don’t ignore the ground—replace bare mulch with native ground covers. This living carpet cools soil, retains moisture, and hosts insects, providing extra food for ground-foraging birds like robins.

3:45 – The golden rule of summer birding: it’s all about connections. Native plants host insects, insects feed baby birds, and your yard transforms into a functioning nursery and critical piece of the local ecosystem.

4:21 – Quick pro tips: plant in the cool morning or evening, pre-soak the planting hole, and mulch well to retain moisture. Be patient—plants focus on roots the first year, but once established, birds will follow.

4:50 – By implementing these steps, your yard becomes more than a garden—it becomes a thriving, bird-friendly habitat that supports every stage of a bird’s life.

5:01 – Summer isn’t dead for birding. It’s the most important season, determining the survival of the next generation. Your feeder serves you; your food web serves the birds.

5:15 – Ask yourself: what will your food web look like this year? Which native plants will you choose to build a living, thriving ecosystem? The birds are waiting.

5:29 – Thanks for watching, and happy summer birding!

The Late-Summer Bloom & Seed Schedule

Understanding when plants provide resources allows you to eliminate gaps in food availability. This schedule shows which plants deliver nectar, berries, seeds, and insects during specific periods when birds need them most.

| Plant Group | Peak Benefit Period | Primary Resource | Targeted Bird Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serviceberry | June – July | High-Moisture Fruit | Robins, Cedar Waxwings |

| Bee Balm (Monarda) | July – August | High-Octane Nectar | Hummingbirds, Orioles |

| Elderberry | August – September | Fat-Rich Berries | Bluebirds, Catbirds |

| Cup Plant | August – September | Water & Seed | Goldfinches, Sparrows |

| Ironweed | Late August – October | High-Protein Seeds | Finches, Chickadees |

The Late-Season Berry Buffet: Fattening Up for Migration

The Elderberry Advantage

Sambucus canadensis stands as the gold standard for August hydration and energy delivery. According to research on berry-producing plants for birds, elderberry produces flat white flower clusters in early summer that turn into purple bird berries by late summer. The fruit is relished by gray catbirds, robins, bluebirds and many other songbirds.

The timing matters critically. Research from the National Park Service shows that serviceberry produces earlier ripening berries (June-July) when competing fruit sources remain scarce, giving those berries a monopoly on bird attention. In contrast, elderberries ripen in August when other fruits compete for attention, but their high fat content and moisture-rich flesh provide exactly what birds preparing for fall migration require.

The berries don’t ripen simultaneously. Purple-black fruits appear on purple stems over a three-week period, creating an extended feeding opportunity rather than a single-week harvest. This gradual ripening means birds can return repeatedly to the same shrub, reducing foraging energy expenditure while maximizing caloric intake during the critical pre-migration fattening period.

Plant elderberry in full sun to part shade with consistent moisture. The shrub tolerates wet feet better than most fruiting plants, making it ideal for rain garden edges or areas with poor drainage where other berry producers fail. Mature plants reach 8-12 feet tall and sucker moderately, creating dense thickets that provide both food and protective cover.

Viburnums for Longevity

Select viburnum varieties based on fruit persistence rather than flower showiness. Arrowwood viburnum (Viburnum dentatum) and blackhaw viburnum (Viburnum prunifolium) produce berries that hold through late summer heat without shriveling, a critical characteristic that lesser varieties lack.

According to research on native berry shrubs, arrowwood viburnum berries are high in fats and carbohydrates, which allow migrants to rapidly refuel, and the berries also contain large amounts of antioxidants. The nutritional profile matches precisely what birds need during migration when they must build fat reserves quickly.

The key to viburnum success lies in planting multiple genotypes. Most viburnums require cross-pollination from a genetically different individual to set fruit. Plant at least two different cultivars of the same species, or mix related native species like nannyberry and blackhaw for guaranteed fruit production.

Unlike elderberries that ripen uniformly dark purple, viburnum fruits change color as they mature. Watch for the color progression from green to pink to blue-black as the signal that birds will begin feeding. Early-ripening fruits get eaten immediately; later fruits may persist into October, providing critical food during the peak migration window.

The Clean Fruit Rule

Native berries provide better nutrition than invasive alternatives like Amur honeysuckle or autumn olive. The difference isn’t just patriotic preference; it’s measurable nutrient density. Native fruits evolved alongside native birds over millions of years, creating berries with appropriate fat content, digestible seed coatings, and nutrient profiles matching avian requirements.

Research shows that birds feeding on native fruits during migration gain weight more efficiently than those feeding on invasive berries. The invasive berries often contain less fat, more water, and seeds with harder coatings that pass through digestive systems without providing nutrition. Birds may gorge on invasive fruits because they’re abundant, but they need significantly more volume to obtain equivalent nutrition.

Additionally, native fruits ripen at times corresponding to natural migration patterns. Autumn olive ripens in October, too late for most songbird migration. In contrast, native dogwoods, viburnums, and elderberries peak in August and September, precisely when birds need them most.

The Nectar Superhighway: Powering High-Metabolism Summer Residents

Cardinal Flower: The Biological Red Flag

Lobelia cardinalis functions as a biological beacon that signals nectar availability to migrating hummingbirds. The intense scarlet blooms stand out against green backgrounds with maximum contrast, creating visual landmarks visible from considerable distances as hummingbirds scan landscapes during migration.

According to research on hummingbird attraction, hummingbirds have evolved to associate the color red with abundant nectar sources. The preference stems from the fact that many nectar-producing plants display vibrant red hues as signals of reward.

Cardinal flower blooms from July through September, filling the gap between early-summer native flowers and fall asters. Each flower spike produces dozens of tubular blooms that open sequentially from bottom to top, providing weeks of continuous nectar production from a single plant. The tube depth and diameter perfectly match hummingbird bill morphology, creating an exclusive feeding relationship that reduces competition from bees.

Plant cardinal flower in consistently moist soil with part shade during the hottest afternoon hours. The species grows naturally along stream banks and wetland edges, requiring more moisture than typical garden perennials. In dryer locations, provide supplemental irrigation during drought periods or accept reduced blooming performance.

Agastache: The Drought-Tolerant MVP

When temperatures exceed 90 degrees Fahrenheit and water becomes scarce, most nectar plants shut down production to conserve resources. Agastache (hyssop) defies this pattern, continuing to produce copious nectar even during extreme heat and drought.

The secret lies in deep taproot systems that access soil moisture unavailable to shallow-rooted competitors. Once established (typically after the first growing season), agastache tolerates extended dry periods without wilting or reducing bloom production. This drought tolerance makes the plant invaluable during late summer when irrigation restrictions limit water availability and other nectar sources decline.

Multiple species offer different bloom times. Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) flowers July through August. Giant hyssop (Agastache scrophulariaefolia) extends the season into September. Planting both species creates a seamless nectar corridor through the entire late-summer period.

Hummingbirds, butterflies, and bumble bees all feed heavily on agastache. The vertical flower spikes reach 3-5 feet tall, creating visible feeding stations that draw pollinators from surrounding areas. Unlike some native plants that require specific soil conditions, agastache thrives in average garden soil with minimal care once established.

Succession Planting for Continuous Nectar

Prevent gaps in nectar availability by overlapping bloom times through strategic plant selection. Begin with early-summer bloomers like wild columbine and native honeysuckle (June-early July), transition to bee balm and cardinal flower (July-August), and finish with ironweed and asters (late August-October).

The goal is ensuring that on any given day from June through October, your yard offers at least three different nectar sources in active bloom. This redundancy protects against weather events (late frosts, heat waves, droughts) that might damage individual species while leaving others unaffected.

Track bloom times in a garden journal. Note which plants peak simultaneously versus those that bloom in sequence. Adjust plant selections in future seasons to fill observed gaps. A yard with continuous bloom supports higher hummingbird numbers than one with spectacular but brief flowering periods separated by nectarless weeks.

Growing Natural Feeders: The Late-Summer Seed Strategy

The Goldfinch Magnet: Cup Plant

Silphium perfoliatum earns its common name from the distinctive way opposite leaves fuse around the square stem, creating cup-like structures that collect and hold rainwater. These natural reservoirs provide drinking water for birds, insects, and small mammals while the plant simultaneously produces seeds that goldfinches consume voraciously.

The dual resource provision (water plus food) makes cup plant exceptionally valuable during late summer when natural water sources decline and seed production peaks. Goldfinches can drink without leaving the security of the plant, reducing predation exposure while feeding. This integrated design attracts more birds per plant than species offering only seeds or only structure.

Cup plant reaches 6-8 feet tall with coarse, substantial stems that persist through winter. These sturdy stalks provide perching platforms for birds accessing seed heads and create vertical structure that breaks sight lines from aerial predators. Goldfinches and other small songbirds feed more confidently when protective cover exists above and around feeding stations.

Plant cup plant in full sun with average to moist soil. The species tolerates clay, occasional flooding, and summer heat without stress. Allow 3-4 feet between plants as mature specimens develop substantial girth. Flowering begins in August, with seed heads maturing through September and October. Leave stalks standing through winter for continued bird use.

The Don’t Deadhead Commandment

Gardeners instinctively deadhead spent flowers to encourage reblooming and maintain neat appearances. This habit directly contradicts bird-friendly garden management. Spent coneflowers (Echinacea), black-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia), and sunflowers (Helianthus) become bird magnets once seeds mature.

According to research from the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, these composite flowers develop UV patterns as seeds mature, creating visual signals visible only to birds. The UV bull’s-eye patterns guide goldfinches, chickadees, and sparrows directly to the most productive seed sources.

The nutritional content of seeds from native composites exceeds that of commercially available niger thistle or sunflower seeds. Native seeds contain oils, proteins, and micronutrients specifically calibrated to regional bird requirements. Birds instinctively recognize and preferentially select these superior food sources when available.

Resist deadheading from August onward. Allow flower heads to dry naturally on stalks. Seeds mature over several weeks, creating an extended harvest period. Goldfinches particularly favor partially dried seed heads where seeds are mature but still attached to the plant, allowing extraction without seeds scattering onto the ground.

Structure as Food

Tall, late-season stalks provide more than seeds. The vertical architecture creates protective structure that shields feeding birds from hawk predation. Goldfinches feeding at ground level face significant risk from aerial hunters. The same birds feeding within the protective canopy of 6-foot tall coneflower stalks gain both food and cover simultaneously.

Multiple plant species create layered protection. Use cup plant for maximum height (6-8 feet), backed by joe-pye weed (5-7 feet), with coneflowers and black-eyed Susans filling mid-level zones (3-4 feet). This graduated structure creates a feeding matrix where small songbirds can move vertically through the height gradient while maintaining overhead protection.

Winter persistence matters too. Sturdy native stalks stand through snow and ice, remaining available to overwintering birds when fresh growth disappears. Cut stalks in early spring only after migratory birds arrive and begin exploring nesting territories, preserving winter food sources as long as possible.

Timing & Planting Tips: The Beat the Heat Protocol

The Morning and Evening Window

Never plant between 11:00 AM and 4:00 PM during summer months. Mid-day transplanting exposes vulnerable root systems to maximum heat stress and soil moisture evaporation, dramatically reducing establishment success rates. Even with abundant water, plants moved during peak heat often experience permanent setbacks from root damage and moisture stress.

Instead, plant during early morning hours (6:00-9:00 AM) when temperatures remain moderate and soil retains overnight moisture. Alternatively, schedule planting for evening hours (6:00-8:00 PM) after the day’s heat passes but while sufficient light remains for work. Both windows provide plants with cool recovery time before facing the next day’s heat.

Cloudy days offer ideal conditions regardless of time. Overcast skies reduce radiant heat and soil surface temperatures, allowing midday planting when cloud cover persists. Monitor weather forecasts and prioritize planting before predicted rain systems when natural irrigation will support establishment.

Root Immersion Technique

Standard planting advice recommends digging a hole twice the width of the root ball and amending soil. Summer heat demands an additional step: pre-soaking the planting hole before installation.

Fill the prepared hole completely with water. Allow it to drain naturally. This pre-soak saturates surrounding soil with moisture that roots can access immediately rather than forcing plants to survive on whatever water you add during installation. The saturated soil also cools several degrees below ambient temperature, providing thermal buffering for stressed roots.

Remove container plants from pots and examine root structure. Gently tease apart circling roots without breaking them. Position the plant in the pre-soaked hole at the same depth it grew in the container. Backfill with native soil without amendments (amendments can create drainage problems in summer heat). Water again immediately after planting, creating a moat around the base to concentrate moisture in the root zone.

Apply 2-3 inches of mulch around (but not touching) the stem. Mulch moderates soil temperature, retains moisture, and suppresses competing weeds. Maintain weekly deep watering for the first month, then gradually reduce frequency as plants establish. Deep, infrequent watering encourages deep root growth; shallow, frequent watering creates shallow roots vulnerable to heat stress.

The Living Mulch Concept

Groundcovers function as living mulch, keeping soil temperatures 10-15 degrees cooler than bare soil while providing additional habitat for beneficial insects. Plant native groundcovers like Pennsylvania sedge, wild ginger, or green-and-gold between larger specimens to create a continuous living carpet.

The cooling effect results from several factors. Groundcover leaves shade soil surfaces from direct solar radiation. Transpiration from groundcover plants releases moisture into the air immediately above the soil, creating evaporative cooling. The combination reduces surface temperatures more effectively than wood chip mulch alone.

Groundcovers also support the insect populations that birds require. According to research from Douglas Tallamy at the University of Delaware, caterpillars transfer more energy from plants to other animals than any other type of creature. Living groundcovers host caterpillars and other insects that feed nesting birds, while bare mulch supports essentially zero insect life.

The Caterpillar Paradox: Why Trees Matter More Than Birdhouses

The 96 Percent Rule

According to research published by the National Wildlife Federation, caterpillars are a primary food for scores of wildlife species, including the 96 percent of terrestrial birds that rely on butterfly and moth larvae to rear their young. This overwhelming dependence on caterpillars explains why birdhouses alone fail to attract nesting birds. Even perfect nest boxes go unused when surrounding habitat fails to provide the thousands of caterpillars required to raise a single brood.

Research from the Smithsonian’s Neighborhood Nestwatch Project found that it may take 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars in a season to raise a brood of five chickadees. Providing this quantity requires not feeders but plants, specifically native plants that host the caterpillar species birds evolved to hunt.

Why Planting an Oak Sapling Matters

A single oak sapling provides more value to nesting birds than any birdhouse you could install. According to research by Douglas Tallamy, Kimberley Shropshire and graduate researcher Desirée Narango, a native oak tree can support the caterpillars of over 500 species of butterflies and moths. In contrast, most non-native ornamental trees support fewer than 10 caterpillar species.

The disparity creates dramatic differences in bird nesting success. Research by Tallamy found that just 5 percent of native plant species are supporting 75 percent of the caterpillars, and 14 percent of native plants support 90 percent of the caterpillars. These keystone plants (oaks, willows, cherries, birches) function as the foundation of functional food webs.

Even a young oak in a 5-gallon container begins supporting caterpillars within its first season. As the tree matures, caterpillar diversity and abundance increase proportionally. A 10-year-old oak might host 50+ caterpillar species; a mature specimen supports hundreds. The long-term value accumulates year over year, providing escalating benefits that static bird feeders cannot match.

Plant oaks, willows, birches, or wild cherries regardless of yard size. Small urban lots can accommodate dwarf cultivars or multi-stemmed specimens managed through pruning. Even apartments with balconies can grow small oaks in large containers, contributing to the urban caterpillar population that feeds city-dwelling birds.

The Keystone Concept

According to Tallamy, if you take keystone plants out of your local food web, the food web collapses, because they are producing most of the caterpillars that run that food web. Landscapes without keystone plants will support 70-75 percent fewer caterpillar species than a landscape with keystone plants, even though it may contain 95 percent of the native plant genera in the area.

This research revolutionizes summer planting strategy. Instead of selecting plants based solely on flower color or growth habit, prioritize plants based on their caterpillar productivity. A yard containing oaks, willows, birches, cherries, goldenrod, asters, and sunflowers creates a functional food web supporting viable bird populations. A yard containing only hostas, burning bush, and Bradford pears provides ornamental value but contributes essentially nothing to bird populations.

FAQ: Solving the Next Search Problem

How do I keep cats away from my summer bird garden?

Domestic cats kill approximately 2.4 billion birds annually in the United States. The most effective solution is keeping cats indoors permanently. For neighbors’ cats that roam into your yard, use motion-activated sprinklers placed near bird feeding and nesting areas. The sudden water spray creates a negative association without harming the cat.

Plant dense, thorny shrubs like native roses, hawthorns, or raspberries around ground-feeding areas. These create physical barriers that prevent cat stalking while providing protective cover for birds. Space shrub plantings 3-4 feet apart to create impenetrable thickets that cats cannot navigate.

Avoid bird feeders placed within 10 feet of cover that cats can use for ambush positions. Position feeders either in completely open areas (15+ feet from any cover) where birds can see approaching predators, or directly adjacent to dense shrubs (within 3 feet) where birds can immediately escape into protective cover when threatened.

Do I need to clean my birdbath more often in August?

Yes. Summer heat accelerates algae growth, bacterial proliferation, and mosquito breeding in standing water. Clean birdbaths every 2-3 days during summer months compared to weekly cleaning in cooler seasons.

Use a stiff brush and plain water to scrub away biofilm and algae. Avoid soaps or chemicals that leave residues harmful to birds. Rinse thoroughly after scrubbing. Refill with fresh water.

For detailed cleaning protocols and safety information, consult guides on cleaning bird baths without chemicals. Proper maintenance prevents disease transmission while ensuring birds have access to clean drinking and bathing water during the hottest months when natural water sources often dry up.

Consider adding a small fountain or dripper to create water movement. Moving water attracts more birds, reduces mosquito breeding, and stays cleaner longer than stagnant water. Solar-powered fountains require no electrical work and provide continuous water circulation during daylight hours.

Which plants attract unwanted birds like grackles?

No plants selectively attract only nuisance species. Grackles, starlings, and house sparrows feed opportunistically on whatever food sources are available. However, certain feeding strategies reduce their dominance while favoring native songbirds.

Grackles prefer ground feeding and large platform feeders. By eliminating these feeding stations and instead providing food through natural plant sources (berries, seeds), you reduce grackle advantage. Native songbirds adapted to gleaning insects from leaves and picking berries from branches, while grackles specialized for ground foraging.

Tube feeders with small perches exclude grackles while accommodating goldfinches, chickadees, and titmice. Weight-sensitive feeders that close under the weight of larger birds prevent grackle access while allowing smaller native species to feed.

The most effective long-term strategy involves creating habitat that supports the insect populations native songbirds require. Grackles feed primarily on seeds and human food scraps. By emphasizing caterpillar-producing plants and reducing seed feeders, you create an environment that favors insect-eating native birds over seed-eating opportunists.

Infographic: Your Summer Bird-Friendly Garden Plan

Conclusion: Consistency Creates Trust

Birds return to yards they can trust. A yard providing abundant June caterpillars but offering nothing in August trains birds to seek resources elsewhere during the critical late-summer period. Consistency matters more than abundance. A yard delivering moderate resources continuously through the entire summer season supports higher bird populations than one with spectacular but brief resource peaks.

The transformation from traditional feeding to habitat creation requires time. First-year plantings provide minimal resources while establishing root systems. Second-year growth delivers moderate benefits. By the third year, mature plantings create the resource abundance that supports viable bird populations. Patience during the establishment period pays dividends through decades of sustained bird activity.

Track what works in your specific location. Note which plants birds favor, which bloom times create gaps, and which combinations produce the most bird activity. Adjust plantings annually based on observed results. Every yard possesses unique microclimates, soil conditions, and bird populations. Success requires adapting general principles to local conditions through careful observation and incremental refinement.

The goal is not perfect habitat but functional habitat. Even small yards with limited space can provide critical resources during summer months when natural areas face development pressure and fragmentation. Your summer planting choices contribute to regional bird populations, supporting species that depend increasingly on backyard habitats as wild spaces disappear.

For more information on supporting summer bird populations, explore guides on attracting songbirds during summer months, understanding which insects birds need, and helping birds survive extreme heat. Understanding which native plants provide maximum benefit and creating bird-friendly garden designs complete the knowledge foundation for summer bird stewardship.